Two tinted glass doors bearing the artist’s name lead into a dark, expansive room whose sterile white walls are noticeably bare. Huddled in the center of the room, occupying hardly a third of its capacity, is a conglomeration of thin wooden boards, each just five or six feet high. From the circular construction leaks a haunting melody: Several different voices can be heard, all playing simultaneously; the cacophony both startles me and draws me closer. Confused, I double-check my location on the museum map. This is supposed to be an exhibition about protest. Where are the bright colors, the bold slogans, the loud cries for justice?

Though it may seem counterintuitive, Sharon Hayes’s minimalist approach to examining the art of resistance is highly effective. The razzle-dazzle of defiance is not lacking, but simply hidden. To fully access the voice of her work, the casual museum-goer needs to put in considerably more effort than what is requested of, say, a Rothko painting or a Brancusi sculpture. Hayes uses constructed and complex environments to successfully stow away her artwork from the rest of the world, whether in the form of wooden walls or a string of sporadically placed human-size projectors, requiring the viewer to navigate through these physical blockades to unveil the genius of her creation. Once you’ve made it through the labyrinth, her insightful and dynamic presentation unravels itself at your feet.

Hayes’s exhibit at the Art Institute is composed of three pieces that track her development: “In the Near Future” (2004-2009), “Parole” (2009), and “An Ear to the Sounds of Our History” (2011). Each piece comes with its own take on protest, as well as its own code of impenetrability.

I circled the wooden blockade until I found an entrance near the back. A single black block—presumably a chair of some sort—was surrounded on all sides by a sea of speakers, which, upon their stands, appeared almost human-like. Taking a seat, the sound of four distinct videos enveloped me, voices overlapping and struggling to be heard. All four television screens mounted on the wall displayed clips of the same woman in two distinct locations: at home, impassively watching her kettle heat up and emit a high-pitched screech, and on various streets filled with protesters, her microphone pushed to their faces as she intensely gazes at them.

Whatever her location, the protagonist of these video clips, which are collectively titled “Parole” (2009), is something of a blank slate: She speaks not a single word, serving instead as a figure upon which innumerable protesters (Hayes herself appears in a couple of clips, and many more of her speeches are given by stand-ins) project their outcries. The overall dissonance of the installation—numerous voices crying out in protest, bright colors flashing on monitor screens, and a crowd of human-shaped speakers surrounding the viewer—simulates the environment of a street protest.

A narrow corridor, separating the room containing “Parole” from that housing Hayes’s older installation, “In the Near Future,” contains her newest work: “An Ear to the Sounds of Our History.” Drawing on her collection of spoken-word vinyl records, Hayes selected records featuring speeches by renowned public figures whose voices changed history—John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr., and Eleanor Roosevelt, among others—and assembled them in a way that she claims to read as “sentences.” Assembled with a retrospective mindfulness, “An Ear to the Sounds of Our History” attempts to reveal which voices have emerged at the forefront of American history’s social activism and which have faded with time.

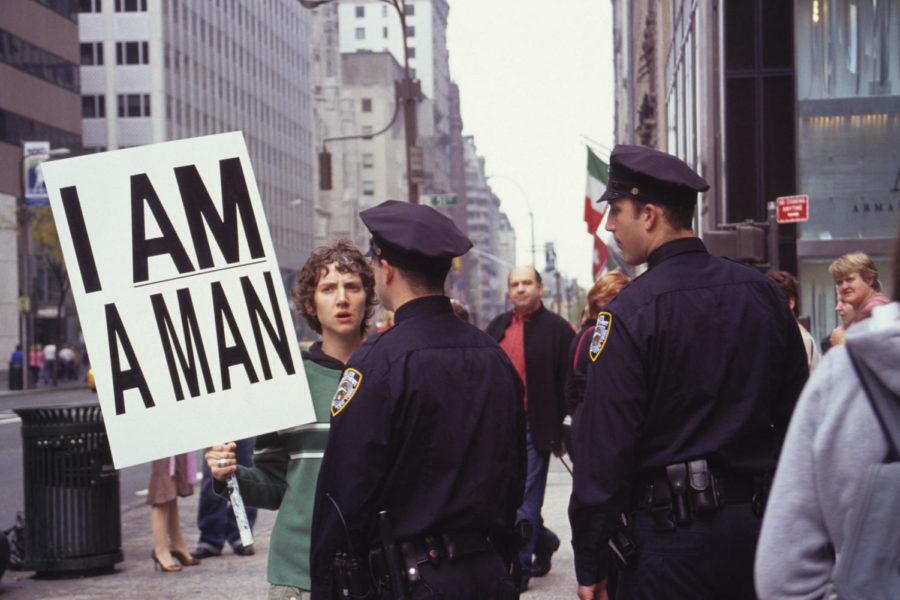

“In the Near Future,” the earliest work in this exhibition (2005–9), has a similar feel to it as “Parole,” threats of claustrophobia aside. Rather than huddling into a small portion of the room, this installation makes use of its entire area. Thirteen projectors placed on stands, measuring about six feet tall to imitate human presence, are placed sporadically throughout the room, clustering slightly at its center. The images displayed on the four walls feature Hayes in a variety of locations—New York, Warsaw, Brussels, and Paris, to name a few—holding posters laden with slogans drawn from earlier protests in history. In one shot, Hayes stands in Central Park wielding a sign bearing the phrase “Who Approved the War in Vietnam?” taken from the anti-Vietnam war protests. In another photo taken in Paris she bears the sign “Rien ne Sera Comme Avant” (“Nothing Will be as Before”) from the 1968 Paris protests. The incessant clicking of the projectors as each switched slides at odd intervals created a low hum, reminiscent of the murmur of a crowd. The images themselves, bright, bold, and rapidly changing, assisted in producing the lively and dynamic feel of a street protest.

The effect of Hayes’s exhibit is something similar to reaching the center of a maze: Gaining entrance into the constructed world of her art is a challenge, and consequently the reward of understanding is made all the more enjoyable. Somewhere between crawling amongst the speakers in “Parole” to find a space to sit down and navigating around the projectors in “In the Near Future,” the physical act of movement gave way to a realization of her true message: Despite the time period, location, or goal of the protest, all acts of public protest reconcile the realms of politics, art, history, and human emotion. And to successfully find the way out of any maze, you need a great deal of retrospection, a feature that Hayes’s exhibit provides generously. Serving as an elegant and thoughtful contemplation of the underlying social, political, and artistic values of public protest, past and present, Sharon Hayes’s exhibition is not one to be missed.