This isn’t your high school homecoming.

Set in the North London slums circa the late 1950s, The Homecoming is a two-act play about a very uncomfortable, albeit, commonplace, occurrence: a man introducing his wife to his family. In this case, that man is Teddy (second-year James Fleming), and he’s hoping to present his wife Ruth (fourth-year Kate Cornelius-Schecter), to his father, Max (third-year Graham Albachten), his Uncle Sam (third-year Fred Schmidt-Arenales), and two brothers, Lenny (fourth-year Andrew Cutler) and Joey (fourth-year Kevin Popp).

The trouble is, Teddy has spent the past six years avoiding all contact with his relatives. He didn’t bother telling them that he was planning to visit, or even that he has a wife, let alone that he’s been married for the past six years and has been working as a philosophy professor in the United States. When Teddy brings Ruth to meet his family, his father’s first reaction is to ask them how they got in, his second, to assume that Ruth is a whore: “Who asked you to bring dirty tarts into this house?” he questions Teddy. From this point on, the tension only grows.

Ruth is eager to bond with Teddy’s all-male family. As Ruth, Cornelius-Schecter plays an intriguing game of male enchantment. Cornelius-Schecter somehow manages to pull off a mix of feminine refinement and aggressive come-ons that is almost suggestive of multiple personality disorder. In the second scene, she’s an exhausted wife who wants nothing more than a breath of fresh air. In the third, she’s a former model who relishes taunting her brother-in-law with sexually charged ultimatums. She’s a mother and a vixen—an enigma that defies all categorization and, yet, dares you to keep trying.

“If you take the glass,” Ruth tells Lenny a mere five minutes after meeting him, “I’ll take you.”

Teddy, on the other hand, finds himself becoming more and more of an outsider. He’s an estranged child, a runaway success story that wants nothing to do with his family and a stranger in what was once his own home. As Teddy, Fleming strikes a curious balance between success and discomfort, employing slight shifts in his posture, facial expressions, and voice to realize his truly nervous, passive-aggressive persona.

Meanwhile, the tension between Ruth, Teddy, and Teddy’s family continues to grow. Teddy urges Ruth to leave for home, but Ruth declines. Teddy grows increasingly excluded. It’s fascinating to watch Teddy—a philosophy doctorate whose occupation consists of teaching others how to think and understand the world—fail to understand the interactions going on around him. “You’re just objects,” he lectures his family. “You just…move about. I can observe it. I can see what you do.” But the audience knows he doesn’t.

“The constant power struggle is key in the play. It leads up to a conclusion in which some of the characters have gained complete power over the others,” Fleming explains.

First written in 1964 by Nobel laureate Harold Pinter, The Homecoming has since won much critical acclaim for its absurdist technique and its willingness to challenge our societal standards of “love” and “family values.”

“Absurdist theater was a stylistic break from realism, where ostensibly realistic situations become colored by unrealistic elements. The play is structured so that the actors’ realistic intentions become jarring and discomforting for the audience,” director William Bishop explains. Still, Bishop says that he tries “to ground everything in realistic intention, because this creates the most honest, powerful acting.”

But, “The Homecoming isn’t simply an absurdist play. The circumstances tend to begin realistically and then progress with increasingly absurd behavior,” Cornelius-Schecter points out.

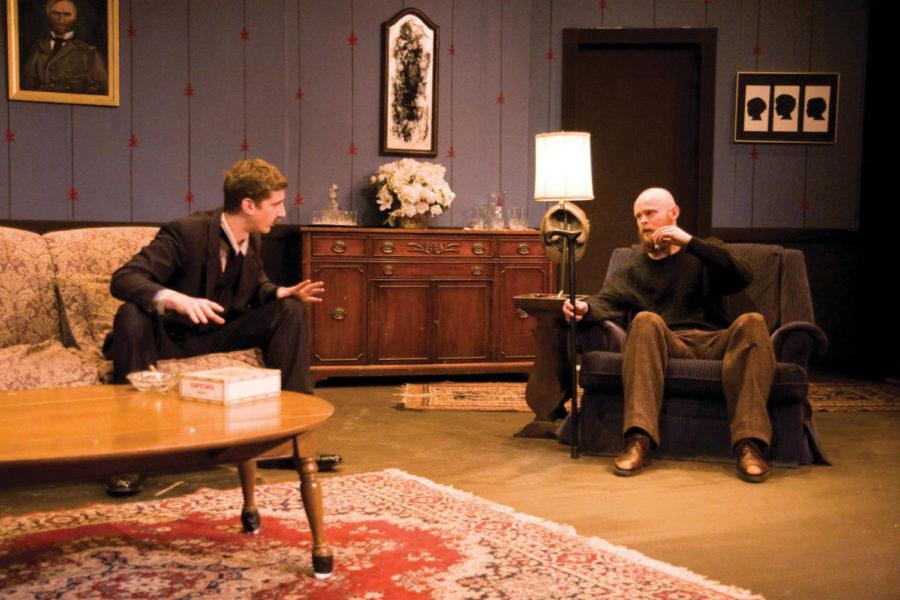

Much madness is built from the minimal words, props, and settings of the play. Albachten, in particular, uses the slightest of gestures to add incredible depth to his performance as Max. In his armchair, he’s a cunning, ominous man who doesn’t hesitate to insult and threaten his sons, but on his feet, he’s suddenly reduced to a tired, old man. He’s willful, violent and weak; he needs a cane. It’s a riveting juxtaposition of traits, and Albachten masters both.

Though both acts are set in the family’s threadbare living room, the play’s limited environment becomes a breeding ground for surprise, energy, and chaos. The ever-present cigarettes (“They’re not real,” Schmidt-Arenales, who plays Sam, explains.) serve as instruments of intrigue and agitation. As Ruth points out, even the movement of her lips isn’t just (and isn’t always) speech—it’s something much, much more.

It’s a creative work of minimalist absurdism. But that’s just it—it works.