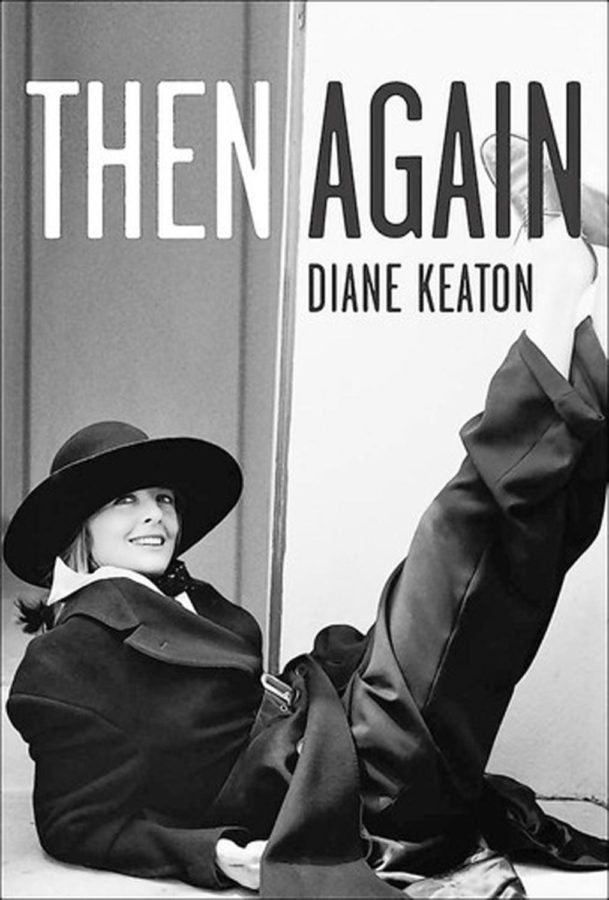

Before Diane Keaton was Annie Hall, she was Di-annie Oh Hall-ie. No bells, no whistles, just a few extra syllables. Her father Jack Hall gave his daughter this neat nickname when she was still an insecure teenager with hair piled three inches high atop her head and a skirt cut three inches above the knee—a fashion statement that predated Annie Hall’s infamous neckties, tailored vests, and trousers by more than a decade. Off the set, and since adolescence, Keaton has almost always opted for an all-black ensemble, very practical shoes, and a hat. Woody Allen once said of Keaton, “She looks to me like the woman who comes to take Blanche DuBois to the institution.” It was a superlative compliment.

However, save for a few illuminating details, Then Again is anything but a book about appearances. Keaton glosses over her gilded career as an actor and a director in order to get straight to the point—this book is about family. More specifically the book focuses on Keaton’s mother, Dorothy Keaton (whose maiden name Diane appropriated when on the verge of stardom), and is meant to serve as a memoir of both mother and daughter. Throughout her life Dorothy filled 85 journals with quotidian thoughts, observations and feelings, sections of which are interspersed throughout the book, along with letters she wrote to Jack Hall in the late 1940s, letters written from Woody to Diane, and, of course, Diane’s autobiographical musings.

Keaton is not a beautiful writer by any means, but she certainly is an honest one. Her voice is simplistic, even a tad darling—she usually opts for “shoot” or “dang it” over a proper expletive and most everyone she meets is “neat”—but always endearingly unpretentious and true to herself. Her style jumps around quite a bit from mildly poetic, to journalistic, to raw stream-of-consciousness prose that mirrors those deeply personal records which Dorothy so diligently kept. “In a way I became famous for being an inarticulate woman,” says Keaton, but she doesn’t give herself enough credit.

Keaton’s storytelling is at its most vivid and poignant when she writes about her mother. In the late ‘50s, Dorothy won the coveted title of Mrs. Los Angeles—a pageant devoted to finding the ideal homemaker. Instead of being tested on skills such as “looking hot in a swimsuit” and “having only the most basic knowledge of politics,” Dorothy was judged in categories like table-setting, flower arranging, bed-making, managing the family budget, and excelling in personal grooming. Keaton deftly handles the “then and again” of gender roles, both within her own family and without. Equally evocative, but much more immediately harrowing, are Keaton’s descriptions of her mother’s heartbreaking battle with Alzheimer’s that come at the end of the book.

Keaton also writes at length about becoming a mother in her fifties, and of her three younger siblings Dorrie, Robin, and Randy. She chronicles her move to New York City at the age of nineteen to study acting at the Playhouse School of the Theatre. Her career took off quickly with a few major theater roles, then leveled off for a few years. During this minor career slump she lived with Woody and developed bulimia, which she would continue to battle throughout much of her early twenties.

Keaton’s offbeat romances with some of Hollywood’s greats are definitely a highlight of the book. Her longtime boyfriend Warren Beatty once gave her a sauna for one bathroom and a steam room for the other as a Valentine’s Day gift. Woody gave Diane names like “Lamphead,” “Worm,” and “Cosmo Piece.” She called him “White Thing.”

It was also thrilling to discover that, just as I and countless others had suspected, Annie Hall is based on a true story. Well, sort of. Keaton doesn’t mention anything about a tragicomic lobsters massacre. She does recount days when she and Woody would sit on “Oldies’ Row” in Central Park making snarky comments about the parade of people passing by, and how she couldn’t meet him for a screening of The Sorrow and the Pity because she was working late. Grammy Hall, immortalized by Allen as a “classic Jew-hater,” is not a fictional character either. When Diane found out she had been nominated for an Academy Award for her role in Annie Hall, her paternal Grammy exclaimed “‘That Woody Allen is too funny-looking to pull some of that crap he pulls off, but you can’t hurt a Jew, can you?’”

For a big-name movie star with claims to incredible staying power, an enviable list of ex-boyfriends, an Oscar, and a healthy heap of je ne sais quoi (or, in her case, la-di-da, la-di-da, la-la), Keaton is still remarkably insecure. Perhaps these feelings come with the Hollywood territory, but she sees herself, instead, as sharing (inheriting is not the right word) her mother’s anxiety and depression. Throughout the memoir, Keaton lets us in on a mother-daughter bond that is painful, wonderful, and essential. The effect is sloppy at worst, mesmerizing at best. She nostalgically remarks at the end of her book, “Sometimes I feel like it’s Again without the Then.” This is Keaton’s enduring charm—that she has always made it feel like old times.