There is perhaps no issue that has been more central to the fabric of American society than the one David Mamet has decided to tackle in his aptly-titled play Race, which opened this past Monday at the Goodman Theatre. Mamet is to be congratulated for giving us a work that never falls into cliché and explores the problem of racial prejudice in America in as sensible a fashion as any theatergoer is ever likely to see.

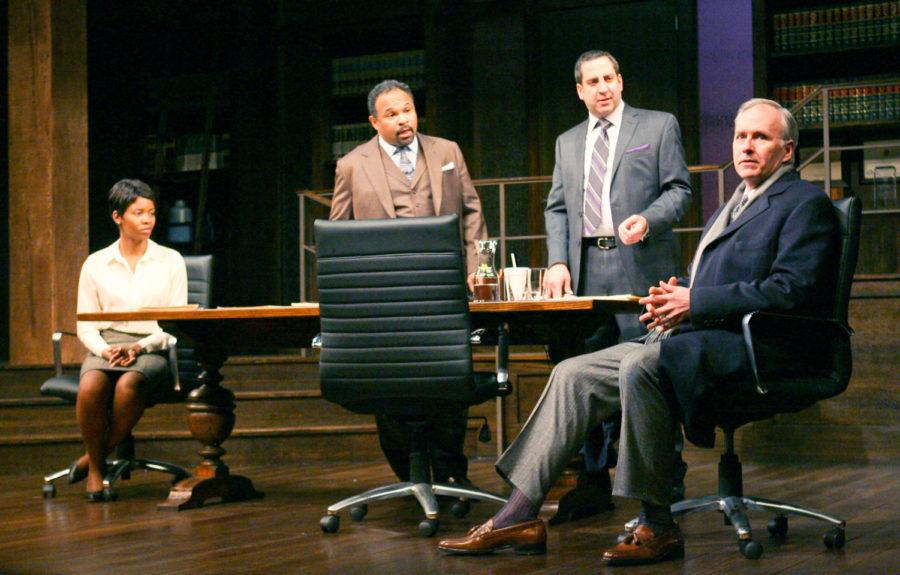

The entire play takes place in the office of the highly successful legal firm of Jack Lawson (Mark Grapey), a white, acerbic, no-nonsense attorney, and his black partner, the pessimistic and equally commandeering Henry Brown (Geoffrey Owens). The legal team has a new prospective client in white, middle-aged Charles Strickland (the excellent Patrick Clear), a billionaire accused of raping a black woman in a hotel room. Strickland’s feeble remonstrance of innocence, met by Lawson’s “Nobody cares, nobody fucking cares,” bring us into Mamet’s world. Lawson admonishes his prospective client for holding the trite idea—at least so far as this play is concerned—that a legal investigation should center around the facts of the case; “ There are no facts of the case,” says Lawson, “…[only] two fictions which each side will attempt to impress upon the jury.” In this way, again and again, David Mamet introduces us to his America. It’s a place where racial prejudice is a mere extension of a more deeply-seated social problem—a tendency to rely too much on cultural assumptions about groups of people instead of our own moral judgments.

Lawson and Brown’s new, Ivy-League-minted African-American clerk Susan (the talented Tamberla Perry) further complicates matters. Her prejudices against the firm’s prospective client are openly acknowledged, and yet, intentionally or otherwise, she effectively hoodwinks the firm into taking the case.

Strickland is told that he cannot rely on his prospective lawyers’ honesty in their dealings. On what may he rely, then? On their “desire for fortune and fame.” Morality does not exist, there’s only the ruthless, mercenary calculus of how to get ahead. In such a world, people make use of anything that might place them ahead of others or others below themselves; race, in America, is the prime example.

In the hands of a lesser playwright, such a scenario would probably have become an overwrought, racially-charged courtroom drama, of which we already have countless examples. It is much to Mamet’s credit that he does not develop Race in this way. The fact that the play only takes place in the law offices of Lawson and Brown and that there is no climactic trial scene or sobering denouement, in some ways liberates the play from its own genre. The play is not only about one particularly racially-charged rape case but also about the underlying social problems that allow such a case to happen.

Chuck Smith has directed a flawless troupe of actors in as good a presentation of Race as we are ever likely to see. Geoffrey Owens is excellent as Henry Brown, he’s an exercise in cynicism taken to the extreme. Patrick Clear powerfully portrays Lawson as a man consumed by the calculating pragmatism which ultimately does him in.

Fortunately, the simple observation that we tend to rely on the conventions of whatever sociopolitical group with which we identify, as the characters do in Mamet’s play, does not imply that morality cannot exist. If all the characters in Race chose to rely on their own moral judgments rather than their own pragmatism, they would have come to a much happier end.