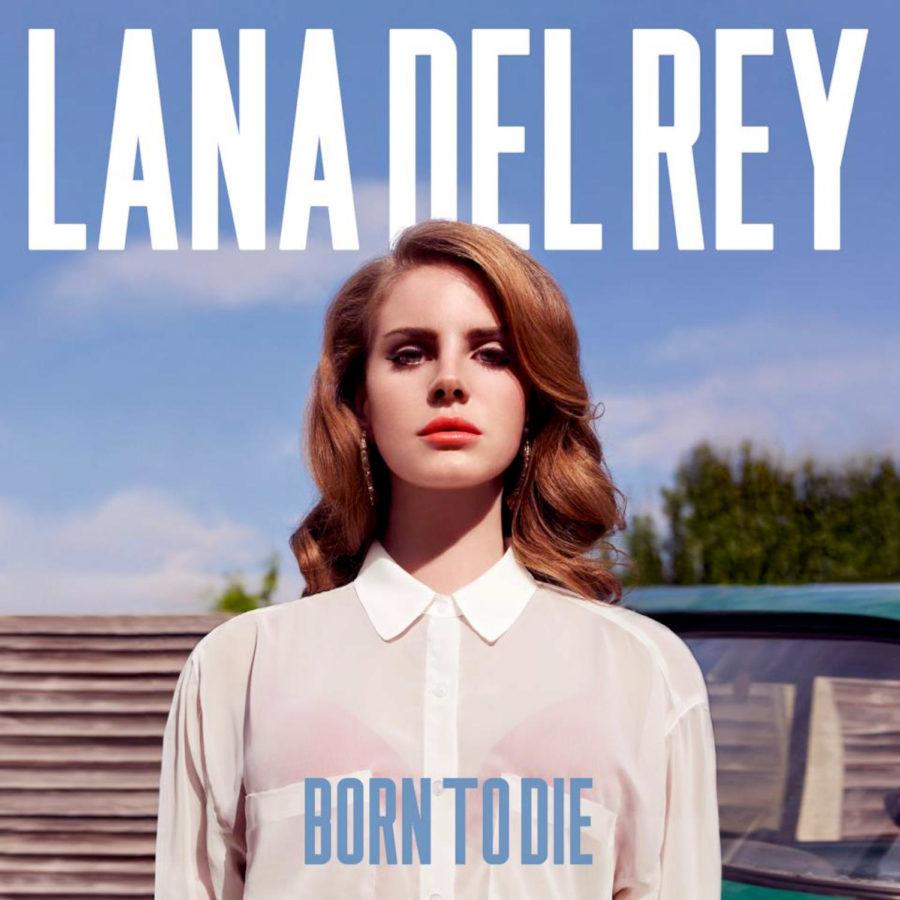

“Everything I want, I have—money, notoriety, and rivieras,” coos Lana Del Rey in one of the closing tracks from her much-hyped debut album, Born to Die, which went on sale last week. I doubt she knew how prophetic that line would prove to be. Famous more for her notorious SNL performance and failed first album attempt than her musical merit, Del Rey has become the Internet’s favorite new punching bag. After listening to her CD in full, I’ve formulated a theory as to why, exactly, this has come to be.

The hate that surrounds Lana seems to be steeped in the fact that the lyrical nature of her songs—all nostalgia and cultural cues crafted over decades to be specifically subversive—stand in direct contrast to what many believe to be her disingenuous image. Lana Del Rey is not a soulful, melancholic, “gangster Nancy Sinatra,” as she calls herself, who croons about PBR and the one relationship that meant everything. She’s Lizzy Grant (her birth name) with a box of brunette hair dye and some lip filler, sponsored either by her new, calculating record label or daddy’s multi-digit bank account (probably, both). Less pointed critics have chosen not to join the war on Lana’s image but don’t understand why her saccharine lyrics would warrant such fuss in the first place.

But my question is, why hold Lana to a new set of standards?

I’d be hard pressed to think of a female pop star in the past two decades who did not, at some point or another in her career, undergo a major image change. Generally, it’s tied to age— Britney and Christina particularly felt the need to express their departure from being “young and innocent” with snakes, shredded half-shirts, and excessive hip shaking. The difference, according to the masses, is that while Britney and Christina underwent transformations, these changes never danced around under any pretense outside of pop. Lana, her critics argue, has crafted an image that tries to subvert its genre, that begs to be taken more seriously than its simplistic nature warrants.

I disagree with these assertions.

Del Rey is, inarguably, a pop singer. Lizzy Grant was, as well. The difference between Lana and Lizzy versus Christina and Britney boils down to pop culture. Britney and Christina rose to prominence in a time where there was no shame in the mainstream. The “hipster” or “indie” or “alternative” subculture had not evolved to the point it has today. It is now a large faction made up of youth that studios recognize as ripe for exploitation. The majority of today’s youth revel in thinking themselves part of the minority. Indie is the new mainstream. We live in a world where Young the Giant plays at the VMAs, where flannels and thick-framed glasses and independent coffee shops are the new…whatever was big at the dawn of the millennium decade. (Maybe bell-bottoms, scrunchies and bagel shops?) Regardless, Lana’s music reflects this—she’s exploiting the mass societal viewpoint of what “indie” is, without subtlety (listen to “This Is What Makes Us Girls,” a song that both references PBR by its full name and sets the female gender back by about 40 years). Lana is catering to the Tumblr crowd, the people who re-blog Instagram’d pictures of girls in high-waisted shorts and roller skates because they evoke some nostalgic, carefree time that exists only in the vacuum of our discontented, Internet-riddled imaginations. Whether it’s Lana’s idea (in which case her lyrical simplicity belies her keen intellect) or (more likely) Interscope’s idea, the songs of Born to Die know what they are and what they have to do; they have to be both catchy and culturally relevant. Listen to them, and you’ll see that they are. Even if Lana’s musical styling isn’t for you, you have to acknowledge that the carefully-crafted mood her songs are meant to evoke work perfectly as a lens into what’s driving our current “subcultural” mainstream. Born to Die is meta-pop, and her album only really fails when it loses sight of this (unfortunately, this failure spans its entire second half, which tries for something other than her trademark, radio-ready nostalgia).

So, I close my argument by again posing the question with which I opened it: Why all the hate on Lana? Did she produce a bad album? In that case, the hate would be warranted. But why then did Born to Die debut at number one in 11 different countries? Is the hate on Lana solely about her industry-sponsored transformation? I’d doubt it because, if becoming more attractive was an American sin, then a bulk of our pop culture would cease to exist. I argue then that the negativity surrounding Lana stems from the unsubstantiated opinion that her music tries to front an authenticity that nothing about her as a person can testify to. Pop is digestible only so long as it doesn’t pretend to be anything else. If Kim Kardashian had tried to use the infamy surrounding her sex tape to become say, a politician as opposed to a reality TV star, then the masses would’ve rioted as well. As a culture full of people who know nothing about themselves, we’ve ironically developed a blinding taste for the self-aware.

I guess, then, my perspective on Del Rey might be somewhat of a comfort for those who hate her on the basis I’ve suggested. I’m glad. Now the rest of us can listen to “Radio” on repeat in peace.