It’s an intriguing premise. Gather a bunch of people together, ply them with food and drink, and sate their artistic appetites with exhibits that examine the social, political, and commercial aspects of food. In Feast: Radical Hospitality in Contemporary Art, showing now at the Smart Museum, a number of artists have attempted to do just that. On Wednesday night, I attended the opening reception for the exhibit.

A line stretching the length of more than half the courtyard spilled out from the museum’s door. Large glass windows comprising an entire wall of the building illuminated the rambunctious scene within: The reception area was teeming with people, all socializing, enjoying the live music, and, most important of all, eating.

Charming waiters and waitresses in stunning outfits were darting skillfully through crowds of attendees. Guests lined the bar and performance arena, talking amongst themselves with great gusto. As I made my way through the jam-packed lobby to the gallery entrance, attempting to navigate around smartly dressed undergraduates and senior citizens alike, a row of sculptures displayed in the middle of the room captured my attention. Their surfaces shone, looking almost wax-like; it wasn’t until I got closer that I realized they were made entirely from butter. While I stood there in total fixation, mouth agape, a man nudged me on the shoulder to inform me that UChicago students had hand-crafted the sculptures under the professional guidance of food sculpture artist Sonja Alhäuser. For me, this was certainly an exhibit without precedent.

Within the gallery space, Feast revealed eighty years worth of “radical hospitality”: that is, the use of food and food serving as an artistic medium to engage the viewer in a way that a traditional painting or sculpture never could. Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), an amorphous sculpture comprised of hundreds of pieces of individually wrapped candy, is designed as an interactive exhibit in which the viewer is welcome to take a piece of candy from the pile. At exactly 150 pounds, the sculpture is the same weight as the artist’s lover, Ross, before he contracted and eventually died of AIDS. By taking (and even more, consuming) a piece of the sculpture, viewers effectually absorb an element of Ross, both immortalizing him and depleting his “life” in the same way the disease did, until the pile empties and is replaced with an entirely new pile. In a sense, through this viewer participation by consumption, Felix-Gonzalez’s lover lives forever.

Other exhibits included photos of Bonnie Sherk’s Public Lunch, a performance piece done at the San Francisco Zoo in 1971 where the artist inhabited a cage adjacent to a live tiger. While the artist went about typical domestic activities, like sleeping, writing letters, and eating prepared meals, the tiger devoured its daily helpings of raw flesh. This startling juxtaposition invoke serious questions about our own efforts to “humanize” food and food consumption and its status as a basic necessity for all living things, regardless of the means and modes of its preparation.

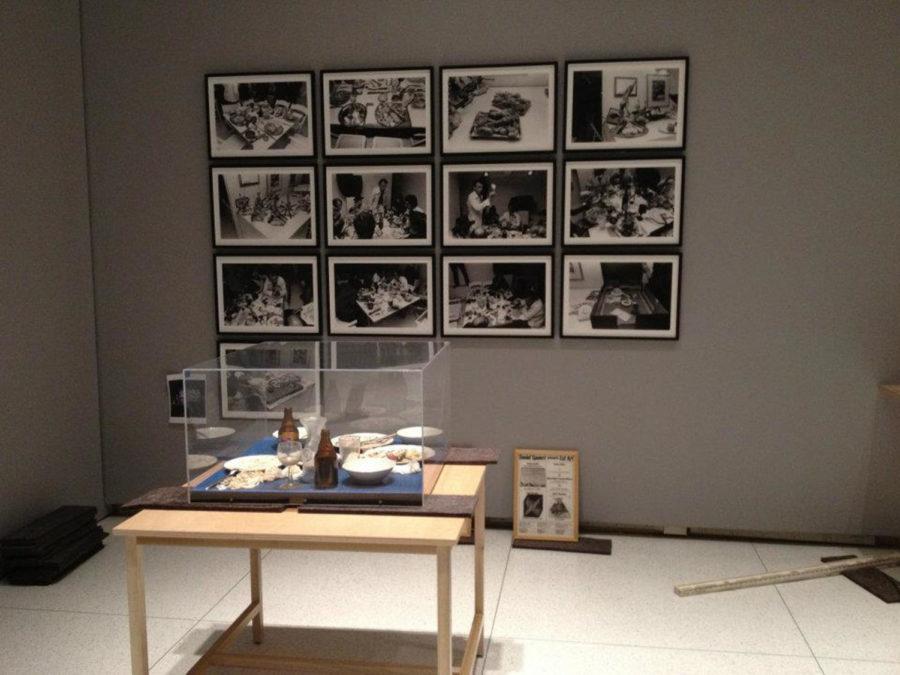

Another room in the gallery featured photos of Al’s Café, a 1969 public installation and participatory artwork that doubled as a classic American diner. Allen Ruppersberg, the artist, served coffee and other “short-order” food that doubled as improvised sculpture. During its short lifespan, it served as a casual meeting place for local artists, blurring the lines between art and food even further.

That night, I left Feast with a full stomach and an entirely revolutionized opinion on what constitutes fine art—which, as far as I’m concerned, means both a three-foot fish sculpture made entirely of butter and a plate of pita bread and hummus. What the exhibit boils down to is the social side of food production and consumption: its cultural, social, and personal significances, and how these ideas are reconciled on the streets, in the barracks, or at the dining table. It’s about food’s unique function of fostering social engagement and promoting humanistic pleasure while unifying us with every other living animal by our necessity to consume. Whether a three-course meal or raw slabs of meat, food is fine art, and fine art is food, so dig in.