Amid the clamor of constant-loop hip-hop videos and live-streaming television ads, spectators at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago are blasted with a neon blur of crack cocaine vials, disfigured stuffed animals, and rat wallpaper. The source of the sensory overload? The exhibition This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s, which explores the turbulence of the years 1979 to 1992, a period marked by political upheaval, massive technological growth, a rise in the rhetoric of gay liberation, and the emergence of mass media.

Organized by Helen Molesworth, chief curator at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, the exhibition includes over a hundred individual pieces and is divided into four themes, “Democracy,” “Gender Trouble,” “Desire and Longing,” and “The End is Near.” Each explores how social change in the 1980s affected art’s production and perception.

“Democracy” opens with an oil painting of Ronald Reagan by German artist Hans Haacke. On the opposite wall, connected to the portrait by a strip of red carpet, a photograph of an anti-nuclear protest draws attention to the political tensions of the time and the incongruity of classical and modern forms of art that became clear as mass-produced images gained sway. Among an assembly of erotic, fleshy shapes hang visions of a blond-haired, blue-eyed Reverend Jesse Jackson. Neon signs around the gallery read: “IT ALL HAS TO BURN, IT’S GOING TO BLAZE. IT IS FILTHY AND CAN’T BE SAVED.” “KISSING DOESN’T KILL,” and“NO TO NUCLEAR MADNESS.”

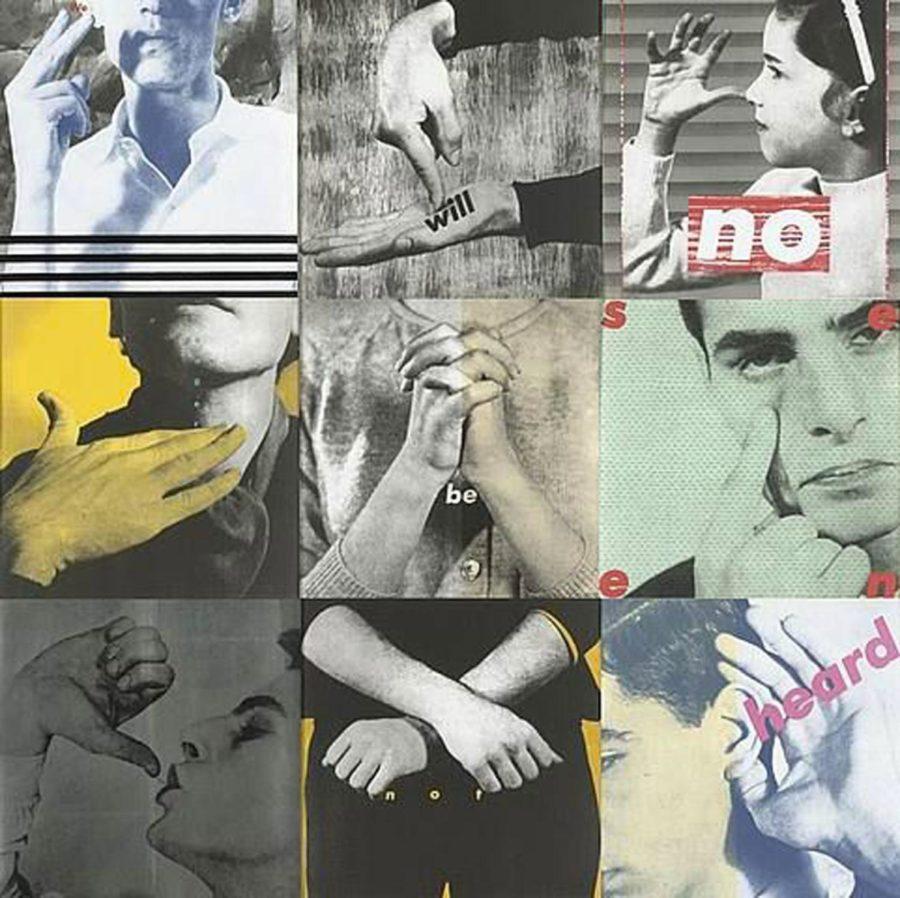

“Gender Trouble” gets its name from Judith Butler, who championed the idea that “gender” is not based on biological differences but rather mental consideration. It addresses issues that resulted from the 1970s feminist movement by manipulating photography and film. Artists like Carroll Dunham challenge the idea of “woman” with works that conflate masculine and feminine attributes, resulting in unclassifiable entities whose aggressive ambiguity targeted contemporary notions.

The next several galleries bombard visitors with a slew of brand logos, metal rabbits, plush pumpkins, and cigarette cartons, as the exhibition delves into “Desire and Longing.” In “Untitled (Buffalo),” a photograph of a display in the National History Museum in Washington, D.C. and one of the exhibition’s most striking pieces, David Wojnarowicz likens the state-sponsored purging of buffalo in the nineteenth century to the state’s neglect of the AIDS crisis. Wojnarowicz also questions ideas about art in a time of mass reproduction.

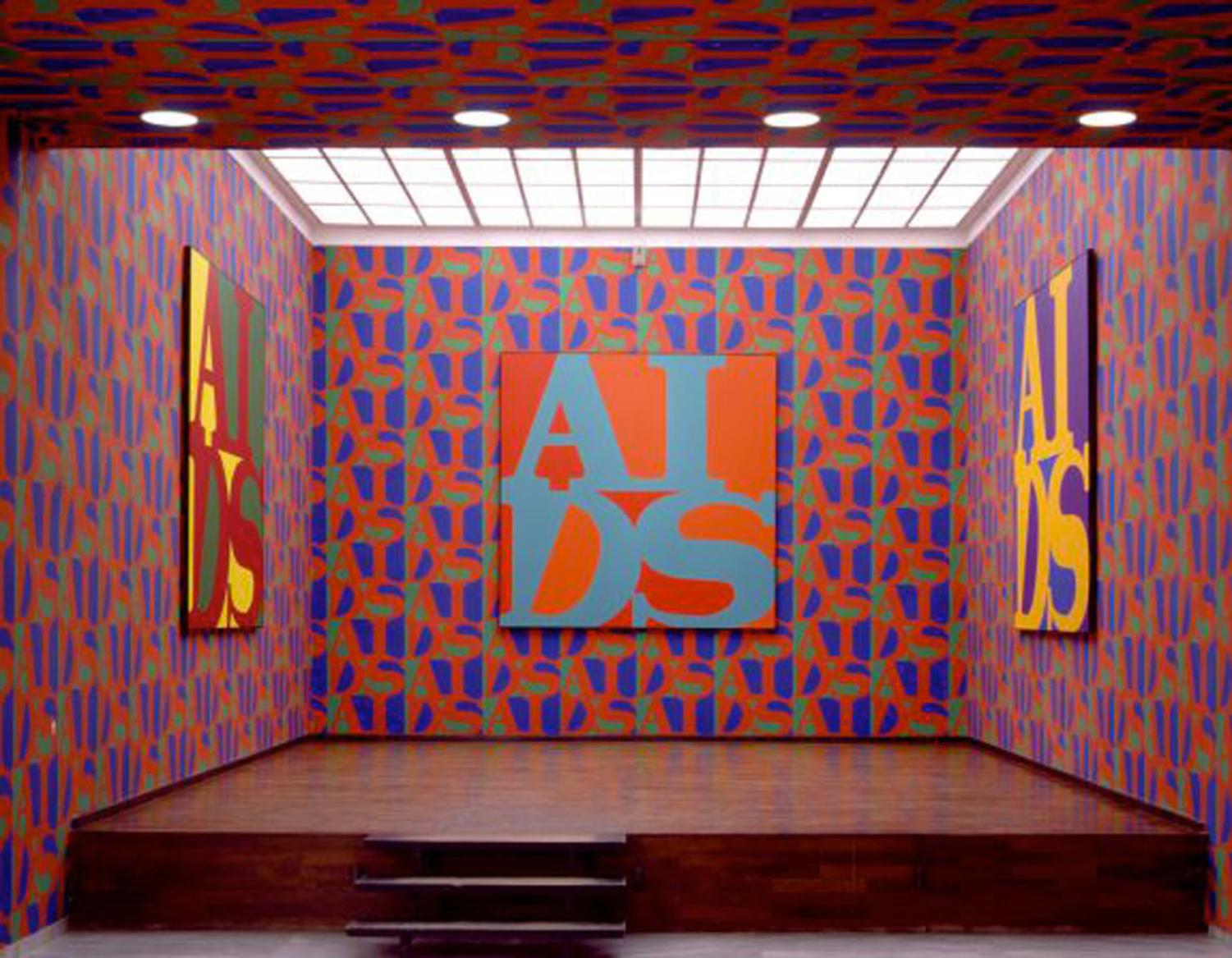

“The End is Near” explores the feeling of closure that pervaded social life in the 1980s. Many feared that the rise of technology would eliminate the need for human-made art; they thought the government’s attacks on overtly sexual art marked the end of the cultural progress made during the 1960s. The section also explores the crippling effects of the AIDS epidemic. Wallpaper that replaces Robert Indiana’s famous red “LOVE” logo with a forceful, almost painful repetition of “AIDS” covers a wall and echoes with the sounds from a nearby viewing room, where a video portrays AIDS victims discussing their impending deaths.

This Will Have Been portrays a more fraught decade than the one we imagine as we gear up for ’80s-themed parties, clad in legwarmers and sweatbands, the one we imagine as we giggle about David Bowie, Pac-Man, and clunky cell phones. The exhibition portrays a dense, arresting view of a time when the development of new practices also marked the unwelcome end of old ones, an era characterized equally by death and growth. As visitors leave, they pass a video of young people freestyling and laughing together; only then do they realize that beneath the exhibition’s surface courses a current of hope.

This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s is on display at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago through June 3.