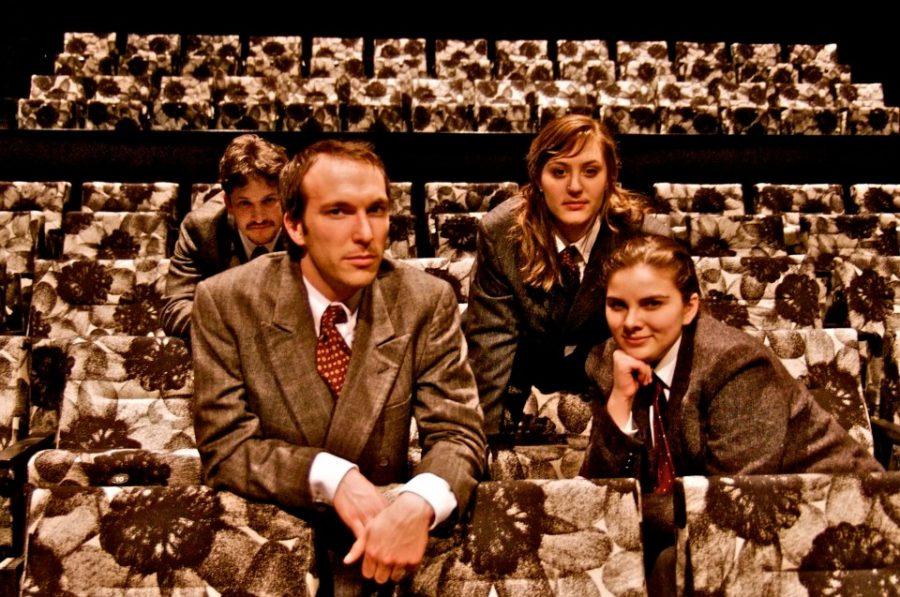

An authoritative teacher, a stuck-up know-it-all, a political prisoner, an earnest student and a crazy axe murderer. According to University Theater’s world-premiere production of An Actor Prepares, which debuted last night in the East Theater of the Reva and David Logan Center for the Arts, these are all Stanislavski. Each actor wore a grey suit, a white shirt, and a red tie. They also had caps, spectacles, and fake moustaches at their disposal. Stanislavski 1 (Colm O’Reilly), the greatest of the eight because of his many lines, everyman appeal, and unique ability to detect irony, was the first to walk the stage with his wild eyes and staid enthusiasm. “I am Stanislavski,” he said gruffly, “and I need a cigarette.”

Konstantin Stanislavski, author, director, drama theorist— and protagonist, as it turns out— wrote An Actor Prepares in 1936 as a handbook for aspiring thespians. This famous method, in a dangerously reductionist nutshell, advocated a method wherein actors truly believe what they are doing on stage. It is not uncommon now to see droves of actors feeling their feelings as they await auditions with tearful smiles and serve up engorged burgers at Planet Hollywood—but in the ’30s, when highly academic style, expertly separated from true emotion, was so dearly cherished, this system was revolutionary, in every sense of the word. This is not to say at all that Stanislavski’s method wasn’t technical; it was painstakingly so. It is this quest for discovering structure and reason, both on stage and off, that motivates much of the show.

Mickle Maher adapted Stanislavski’s book for the stage, and he seamlessly weaves the master’s words into his own creation. The play starts with Stanislavski, the smoker, and moves quickly to Stanislavski the starry-eyed student (Mildred Marie Langford), who, in his effort to hone an honest craft, rubs chocolate on his face to faithfully portray Othello in his drama class. Desdemona is played by a small silk cushion that materializes out of Stanislavski’s little brown briefcase. Maher does a brilliant job cranking out these witty little theater jokes that had all the English professors in the audience in constant titters.

This play may contain the quick, questioning sentences of Beckett and the meta-theatrical fun of Pirandello, but it also occupies itself with a certain level of specificity of place and time that these absurdist works often lack. From the beginning, it is very clear that we are in Moscow circa 1935. Stalin is in power, we are hiding from the terrible political forces that plague Russia—but since we are in exile, we are also isolated, and there is a very real curtain between ourselves (Stanislavski and the audience) and the rest of the world.

This curtain, however, slowly and wonderfully deteriorates as the play progresses, and its focus concentrates more on Stanislavski’s inescapable ties to that outside world and the political crimes committed against those who were dear to him. Diana Slickman (Stanislavski 5), Stanislavski’s former student who was murdered many years later by the government, is bone-chillingly dry and quite effective, whereas Jason Shain’s portrayal of his assassinated nephew is nonchalant and shockingly brief. In other words, not very believable.

However, most of the play is remarkably easy to believe, though what the audience sees is technically unbelievable. Maher could have easily turned Stanislavski’s text into a “three-legged giraffe,” (the term Stanislavski gives to his own manuscript once it has been butchered by his slicing-and-dicing editor), but, instead, it is a graceful and well-balanced four-legged giraffe, which aims high and gets there. The audience wants to believe what Stanislavski’s method teaches them just as badly as Stanislavski wants to light up his cigarette. For this reason, after just half an hour of this imaginative, impactful work, it seems perfectly acceptable that a woman smashes into view through the Styrofoam back wall of the stage, grins through the mushy wreckage, and says, “I am Stanislavski.”