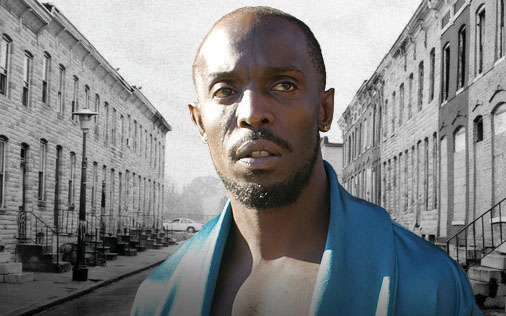

More than any other series, those who love The Wire are prone to overstating both its greatness and the qualitative disparity between it and other TV shows. In the eyes of die-hard fans, The Wire is the greatest, most important TV show of all time. As a matter of fact, it’s not really a TV show (Wikipedia helpfully calls it a “visual novel”); instead, it’s capital-a Art, and one can count the number of programs that approach it in quality on one hand (The Sopranos, Mad Men, and…?).

The Wire’s degree of critical and popular acclaim brings up a few thorny questions. Is it that different from other TV shows? Does it transcend the limitations of the television medium? And if the answer to both of these questions is “no,” then why do people continue to believe otherwise?

The Wire is undoubtedly a deep, complicated show, but there are various aspects of it that are unmistakably “TV”: irrelevant and uninteresting romantic side-plots, a few flat, one-dimensional characters, and the cheesy, soundtracked end-of-season montages that show the predictably horrible fates of the show’s protagonists. There’s a basic tension at the core of The Wire that helps make it so fascinating: Is it a TV show or is it High Art? Can it be both?

It’s not altogether clear what it means for a TV series to be art yet. Does it mean guaranteed longevity? Maybe, but consider The Sopranos, perhaps the one show with comparable critical cache and at one time an integral part of popular culture in a way that The Wire never was. And yet, I’m not sure any of my current TV-loving friends, who were all too young to watch the show when it first aired, have gone back and seen the first season. The importance, renown, and popularity that The Sopranos experienced at the turn of the century seem really strange now. It’s possible that TV as a medium is just not conducive to masterpieces. Perhaps it has something to do with the fact that five seasons of a TV show, with 10–13 hour-long episodes per season, add up to a fairly substantial time commitment—especially when there are other shows running now.

So, there are reasons to doubt that The Wire, or indeed any show, can be permanently canonized the way a great film or novel can. But regardless, let’s accept the now general consensus that The Wire is the greatest show of all time, and ask why this view is so widespread. Part of it is, of course, that it was indeed a well-made, thought-provoking, high-quality show. But there are other factors to consider. Clearly, it’s the kind of TV show that goes a long way toward reaffirming the political views and social values of the people and critics most likely to watch it. And it is also the kind of show that is likely to trick a viewer into thinking that he or she is an expert on drug policy (after watching Season Three) and education issues (after watching Season Four), without making said viewer feel like she is working very hard to gain her expertise. The Wire’s social consciousness and absolute commitment to authenticity make it cool among certain target demographics, in a way that Breaking Bad could never be. All of this inevitably plays a part in explaining why the show is so beloved.

I’m not opposed to the idea that TV shows can be great art or that they belong to our popular culture canon. But I’ve always appreciated how democratic discussions about television are and just how little room there is to be a pretentious ass when you’re talking about a sitcom. There’s something vital and exciting about the fact that we don’t (as of yet) think of TV shows as masterpieces the way we do films or novels. Maybe you are illiterate and uncultured if you’ve never read Hamlet or listened to Beethoven’s 9th, but it would be preposterous to make the same claim about not having seen Seinfeld (an over-rated show if there has ever been one, by the way) or The Sopranos. Given this general atmosphere, it is particularly jarring to hear from a fan of The Wire about how the show “spoiled” him and rendered him unable to watch more pedestrian fare like, I don’t know, Dexter or something.

To be clear, I’m not sure “great art” is a meaningful or useful way to talk about aesthetics, but if we’re going to have it as a category, then The Wire is as good a candidate as most for the label. But sometimes I get the feeling that the show I watched and the show most fans watched were not the same. To my eyes, The Wire wasn’t a revolution in TV storytelling (except, perhaps, in ambition) and it had many of the same flaws that other TV shows do. This doesn’t really bother me, because I find nothing shameful in the TV format and see no reason to place The Wire in an alternative category like “visual novel.” It was a fine show; it had a lot to say about a variety of complicated social and political questions and it did so through a multitude of lovable and unforgettable characters. To me, at least, this is enough.