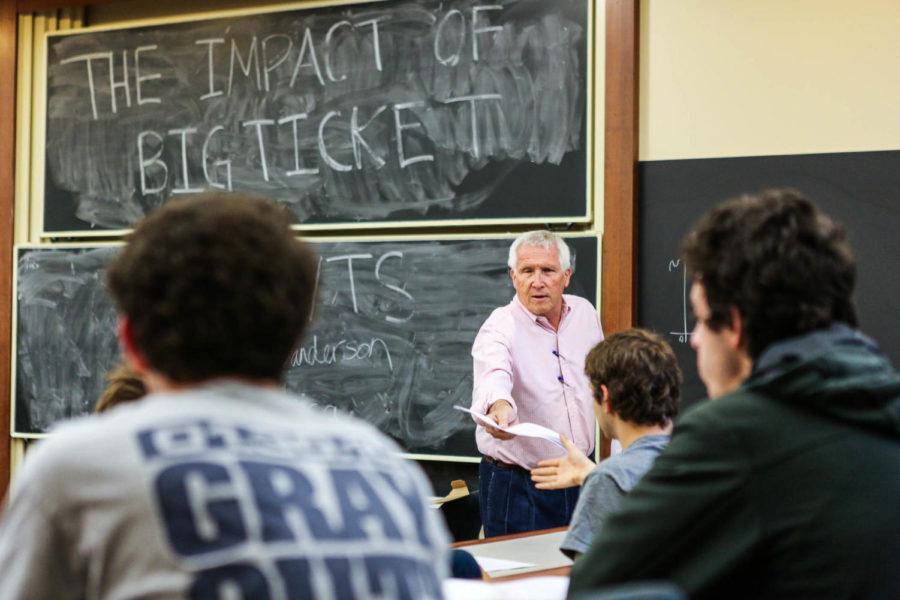

Chicago didn’t get its money’s worth by hosting this weekend’s North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) summit, concluded economics senior lecturer Allen Sanderson on Tuesday.

“The bottom line is I, and most economists, don’t think ‘big-ticket’ events do well economically,” he said. “And that’s a generous statement: Zero dollars is not the lower bound.”

In a recent article in the Chicago Tribune, Sanderson critiqued the city’s economic forecast study, conducted by financial services firm Deloitte, which estimated that the NATO summit would bring $128.2 million in new spending to Chicago.

But Sanderson considered the estimate grossly inflated. “My rule of thumb is, move the decimal on the estimate one place to the left, and it’ll be pretty accurate,” he said.

Sanderson cited two economic principles that the city’s estimate neglects: substitution spending and the “leakage” of spending to outside Chicago. Sanderson’s research shows that NATO-induced spending merely substituted normal spending by people who didn’t come to the city because of the summit.

“May is a big month for conventions at McCormick Place, and this year all of that got cancelled to prepare for NATO,” he said.

In fact, restaurants and shops actually did worse during summit weekend because Chicago residents tended to stay home to avoid transit and security problems, according to Sanderson.

“But even if that level of spending did occur, the estimate is still inflated because not all of that money stays in Chicago. A great portion of that spending ‘leaks’ out of the Chicago economy into corporations and shareholders,” he said.

Though Sanderson considered the summit a success because it may have given Chicago international media attention, he doubts that it brought any net commerce or jobs to the city. He also criticized mayor Rahm Emanuel for justifying the conference as “free” to taxpayers because private donors covered the summit’s costs.

“The mayor talks like $128 million just fell from the sky,” Sanderson said. “But like all spending, these donations entail opportunity cost. The costs covered by private donors and corporations would have been spent elsewhere in the Chicago economy. This is merely substitute spending, not ‘new spending,’ though that’s how it’s being treated.”