If Wikipedia is good for one thing (your professor will say that’s an overstatement), it’s self-affirmation. Take, for example, the “List of notable University of Chicago alumni.” What an article.

It’s a long list, certainly, cataloging the brightest luminaries to have ever called that scrap of Hyde Park between East 55th Street and the Midway home. Included are Tucker Max, A.B. ’98–author of Assholes Finish First–and a hot mess of economists.

And then there’s you, young first-year.

Putting aside that dirty word that starts with “N” and ends with “-obel,” the WikiList actually offers some valuable insight into the caliber of person that has stalked the University’s Brutalist fluorescent bookstacks and Neo-Gothic quads, and with whom all Chicago students now share something in common.

But the Internet is nothing if not accessible; the site is always available for your perusal. Alumni themselves, on the other hand, are not so available, which is a shame, since, as it turns out, they’re quite useful for things other than annual giving.

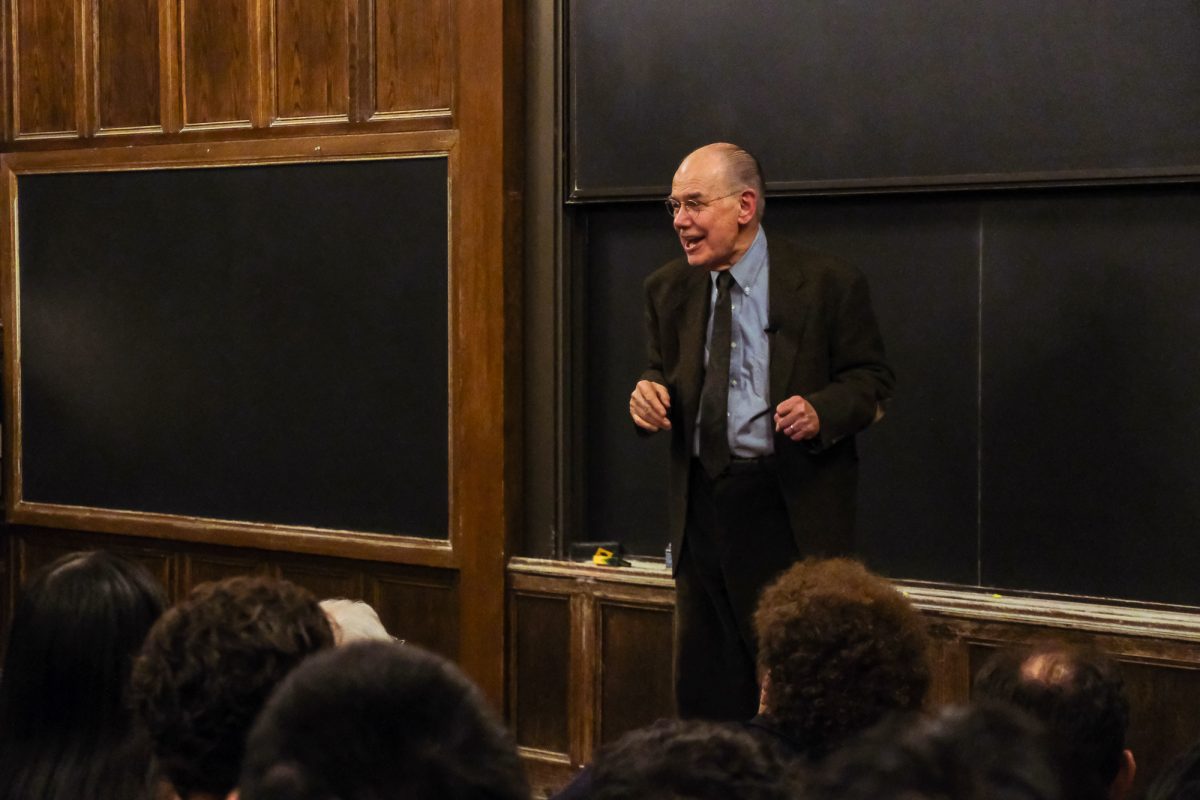

Rick Perlstein, A.B. ’92 graduated from the College with a degree in History. While he was here, he spent his time plunging into the Second City’s rich arts scene, writing for the Maroon’s Grey City Journal, which, apparently, was far more “alternative” than it is now, and generally living his life as “the prototypical University of Chicago student.”

At a tender 18 years of age, Perlstein wanted nothing more than to be a history professor. He went through the Core enamored with the humanities classes of English Professor Lauren Berlant, who still teaches here. He loved jazz. Today, Perlstein, 42, still loves jazz, and he and Professor Berlant are now good friends.

He also covered Washington, D.C., as The Village Voice’s national correspondent, has been called upon to provide political analysis for The Washington Post and The New York Times, befriended the late William F. Buckley, and has written two books, including Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America, which, according to Time, President Barack Obama picked up once for a few pointers.

Back in 1992, however, prototypical Perlstein found himself facing the prototypical collegiate dilemma. “I wasn’t too ready for genuine economic activities,” he said, in a champion example of understatement. So, instead of entering the job market, he went back to school.

Two years later, in a move he compares to “stepping off a cliff,” he set out for New York City to pursue a life in essay journalism. He spent six of the next eight years freelancing before covering the 2004 presidential election for the Voice and writing his first book, Before the Storm, about Barry Goldwater’s 1964 bid for the White House.

All the while, Perlstein was sure to keep one foot in academia – a priority he said was drummed into him at the U of C. Even then, career counseling was never much of a concern, despite the fact that in 1992 the economy was still convulsing in the throes of recession.

“The fact is that people who are coming to the University of Chicago have before them a tremendous opportunity,” he said. “It would be kind of a shame and a waste to turn your back on that and make this all about a career.”

If job hunters find that sentiment at all frightening, consider also that Perlstein regards musicians, with their long hair and slavish devotion to their own souls, to be his “vocational role models.”

However, at a time when every week seems to bring in another apocalyptic prognosis about the uselessness of a college degree, and U of C students are pouring into career-planning sessions at record rates, it might not be a bad idea to take the example of a man–who apparently has the ear of the President–as a source of fuzzy reassurance when that unpaid summer internship in Paducah, KY falls through.

“I have a career because I wasn’t a careerist,” Perlstein said.

Now, take Dave Kehr, A.B. ’75, another brainy humanities-type. Kehr has been a film critic for nearly 40 years, starting while he was at the College. From his workplace at Doc Films, he submitted regular movie reviews to the Maroon and interned at the Chicago Reader, offering his own take on the day’s films for the whopping sum of five dollars a pop.

As Kehr would tell it, life has been easy.

Perhaps another prototypical U of C student from the Chicago suburbs, Kehr pined for the professorial lifestyle as a first-year, hoping to teach English literature some day. Slowly, that idea melted away under the glimmer of the silver screen, and after graduation Kehr happily leapt into gainful employment virtually from day one, writing reviews full-time for the Reader. From there, it was the New York Daily News, and then onto The New York Times, where he has been a reviewer since 1999.

“I have had no difficulties at all, which is not what everyone wants to hear,” he said. No, it’s not. But, of course, Kehr isn’t including his college days in that tidy summation of his professional career.

“[College] was very demanding,” he said. Apparently, U of C students are skilled at understatement. “You realized that you didn’t have weekends, and you didn’t have so much of a social life.”

It all worked out in the end though, even the parts that got dropped along the way–Kehr just took up a position teaching a graduate film criticism seminar at New York University.

But then, the College couldn’t have been all modernist German cinema and Bunker Hill sieges in the Regenstein. Asked whether he had any regrets about his time at U of C, Kehr waxed smug.

“Not for publication,” he said. “It was the ’70s, man.”

That it was. But for the here and now, first-years, mind the 120 years of crash test dummies that have preceded you, many moving on to great things, not all of them winning N—bel P—zes (gasp), but legions of them leading happy lives writing books that get read by the nation’s president.

And that isn’t so bad.