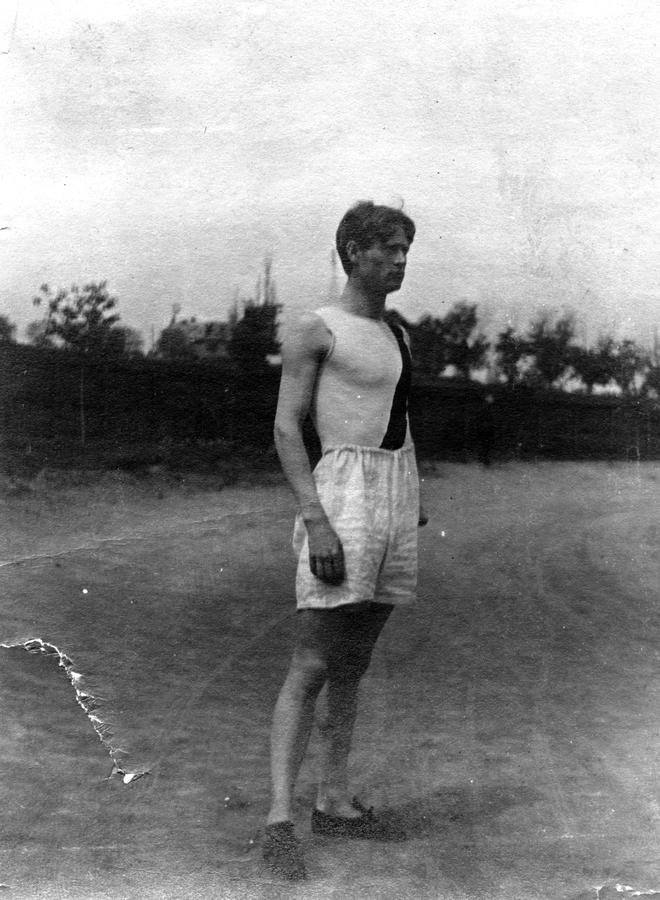

On July 14, 1900—Bastille Day—on a dirt and grass track on the outskirts of Paris, a recent University of Chicago alum named Charles Lindsay Burroughs represented the United States in an Olympic Games that is notable mostly for being the messiest ever. He won no medals. He returned stateside, mainly to study more, but also to teach history. Less than 18 months later, he was dead at 25. Typhoid. A brief obituary (more a notice) in the Daily Illini, printed out of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, ran on Thursday, December 18, 1902. It was his final appearance in the press.

Charles Burroughs was something of an early celebrity at the U of C. Long before F. Scott Fitzgerald gutted the term and made it synonymous with “tactless meathead,” he was the picture of a Big Man on Campus—not just liked but respected, with a historian’s acuity, and above all a near-peerless athlete. His feats as a sprinter during the rough-and-tumble adolescence of American athletics brought him to prominence in the collegiate and international arena. If it were the 1890s, and you were a sports reporter at the Tribune or at any Big Ten school paper, you knew him well.

Burroughs was born in a nowhere part of the country, back at a time when there was more new nowhere cropping up every single day. Long before his legs carried him off to school and beyond, to become the University’s favored son, a renowned sprinter, a friend of the Harper family, and finally, suddenly, a footnote, Burroughs’ feet were planted firmly in Washington County, Iowa.

The improbability of Burroughs’s route to Chicago is enough to make one both find and renounce a faith. His parents, James Reaves Burroughs and Bathsheba Mary Gray, both West Virginians, got hitched on the Fourth of July when he was 20 and she was 18. By the time Charles was born, Bathsheba and James had started a seven-member household in the far-off city of Washington, Iowa, more than 700 miles from home. Hardly a generation separated Burroughs from a time in which he would have been trespassing on foreign soil. In the early 1800s, eastern Iowa was divided among three Native American tribes. By mid-century still, the closest vestige of federal power was a fort built on a limestone outcropping in the middle of the Mississippi River, aptly dubbed Rock Island, a holdover from the Black Hawk War. The pioneer phenomenon was real: Accounts from this time are full of large families and young widows. As the state became more settled, people would still get lost looking for the capital. The town of Washington paid a sheriff $34.98 to conduct a census, and he counted 283 people.

Charles was precocious. He graduated high school by the time he was 14, and continued his studies at Washington Academy, a public school. Details as to when, exactly, he entered and left the academy are murky. But somewhere between his high school graduation and his 19th birthday, he discovered an opportunity back east, in sinful, meatpacking Chicago. He joined the U of C’s class of 1899 and, shortly thereafter, the track team. He dominated the Big Ten conference, sitting for three years as its champion in the 100-yard dash and the now-obsolete furlong (220 yards), the conference record for which he set at 21 and three-fifth seconds, hand-timed. It is alleged by a group of Olympic historians that he matched the world record of 9.8 seconds in the 100 meters at a meet between the Chicago Athletic Club and the New York Athletic Association, but the anecdote has escaped much documentation. Burroughs graduated in 1899, decorated and well-liked, and remained at the University to do graduate work.

The year that followed is an example of how worlds can collide. In 1900, Paris delivered the fifth and last of its sensational World’s Fairs, opting to host the Olympics as an irresistible side attraction. The politics that led to this point are too baffling and well-documented to be repeated here. Suffice it to say that the games very nearly would have stayed in Greece were it not for several spates of frenzied diplomacy. Instead, Paris got the gig it always wanted, just as Burroughs, age 23, was hitting his stride.

The French games were something of a sham. Due to a combination of backroom dealings, eleventh-hour demands, awkward scheduling, and poor facilities, nobody is really sure what the hell happened. Sporting events were clumsily integrated into the ill-fitting categories of the fair. Athletes competed without even knowing that there was an Olympics on. Certain events, like archery, were open to anyone who wanted to give it a shot, and so had thousands of competitors. The youngest gold medalist was a young rower immortalized in the record books as “Unknown French boy.” Even contemporary reporters referred to the games as “Olympian” only as a kind of bad joke, or as convention. The whole mess endured for over five months. But people read about it, and countries still felt obligated to at least send their best, if only to show off.

The Americans shipped overseas 73 of their own, only seven of them women, many of them organized by amateur clubs and universities. Amos Alonzo Stagg, famed wizard of the U of C’s early gridiron days, mustered a track team. People cared most about the runners. Dispatches from the finish line were printed around the world, and, in Paris, the races were treated as the main event. This is strange to consider, since the French didn’t bother to construct a regulation track, but instead hosted the events on 500 meters of uneven dirt terrain in the Bois de Boulogne, a wooded park on the eastern bank of the Seine. Discus throws got lost in the trees. It was hot.

Burroughs took his qualifying heat in the 100-yard dash. In the semi-finals, however, he fell into third, edging out fellow American Dixon Boardman but losing to the Aussie runner Stanley Rowley. The race was so irregular that the newspaper accounts of the day conflict as to how many runners even took part or who won what.

In other words: It was all in good fun. Even athletes who were cognizant enough to realize that they were racing in an Olympics had little reason to care about the career significance of anything achieved there. Meanwhile, it was still Paris, in 1900. Dyspeptic Frenchmen would later wring their hands about realpolitik and grumble that this one last great fair had succeeded only in revealing how far France had fallen from its glory. (The Americans and the hated Germans showed up well.) But more than 50 million people poured into the city that year, just to see works of Rodin, works of Klimt, a literal Palace of Progress, a Palace of Fine Arts, and electricity (!), so much electricity, even a Palace of Electricity, built in the shadow of the Eiffel Tower. Even from beneath the trees in the Bois de Boulogne, Burroughs couldn’t have missed all of it. And when he returned home, it was to study.

While at the U of C, he continued to teach history at the Southside Academy, a precursor to the University Lab Schools. In 1901, he received a fellowship for European history at the University of Pennsylvania. He was then sent off, alongside Samuel Northrup Harper, son of William Rainey Harper, the University’s president, to continue his studies in Europe. Of course, he returned to Paris—the Sorbonne.

The rest is, as they say, very sad. Burroughs was impossibly popular. At college, people loved him—peers, athletes, even faculty. He was elected class president. He was chosen, unanimously, as the first undergraduate ever to speak at his own convocation. He played the mandolin. Upon receiving news of his death, the Chicago Alumni Club announced a series of resolutions solely in praise of Charles. They called him one of the University’s “most dearly prized and most highly honored sons.”

Burroughs never married, and left behind no children. Whatever might be called his “legacy” exists exclusively on paper. The line ends in Paris. Interestingly, both his dad and his mom were dead by the time of his Olympic performance, but not by much—James died not more than two months beforehand, in May, 1900; Bathsheba in January of the same year. Who knows what was on his mind as he blew past Dixon Boardman in the qualifying heat of the 100-meters? Electricity, maybe.

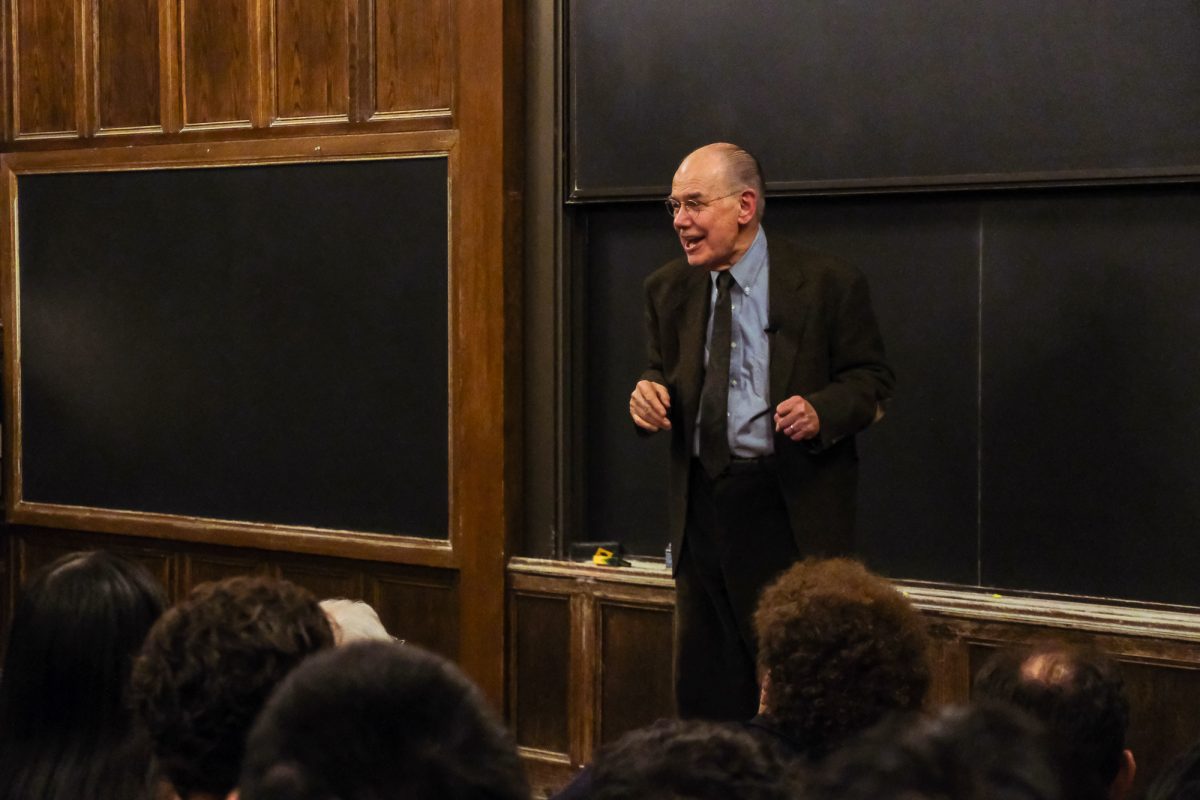

It was Sam Harper who sent the news along. First to the University of Pennsylvania, and then across the country. The Philadelphia Inquirer ran an obit on December 7, 1902. Harper would go on to become one of the keenest experts on those funny folk, the Bolsheviks, and was the first modern American to really devote an academic career to Russia. What is really astonishing, out of all of this, is the fact that, although Burroughs was by no means a superstar—or even a star (others overshadowed him athletically, and theirs are hardly household names)—it is possible to piece together a muddled, just impressionistic, but fairly comprehensive portrait of the man, who was born into a setting totally hostile to the cultivation of greatness: in a forgettable town in a forgettable county, at a time when many Americans were still thinking about That War, though almost none of them were Iowans. He excelled there and, like many adolescents with the talent and the means, he escaped. He quite literally ran to the world’s greatest stage at the dawn of its most tumultuous century. And as if that weren’t a high point, he came home to study and learn more about the world he had only glimpsed while whizzing around in thigh-high track shorts. And he went back, not sated. And there he died, likely in bed, possibly delirious (typhoid is slow, but it rages), news of his death relayed, “by cablegram,” to his Alma Mater, by the oldest son of his Alma Mater’s president, and, from there, to someone, somewhere, in Washington County, Iowa.