Late-summer evenings leave campus quiet and empty in the dying light; a couple Thursdays back, though, it was a different scene entirely. Just shy of five o’clock, a crowd made its way out of the Renaissance Society, located on the fourth floor of Cobb Lecture Hall, and headed across the length of the Main Quad toward the Oriental Institute. The museum’s Breasted Hall was full of spectators, all eagerly awaiting the evening’s talk with Danh Vo, whose exhibit Uterus had premiered at the Society less than an hour before.

Hamza Walker, Associate Curator for the Renaissance Society and Director of Education, sat house left, grinning under the stagelight. After a brief introduction of the exhibition, he called Danh Vo to the stage. Vo emerged from the audience, cautiously took his seat, and defensively crossed his arms and legs. In his aloof and tightly bound manner, Vo mirrored his artwork.

Walker started with simple questions: Where did you find influence for the title of the show? To what degree do these works serve as a biography? A few questions concerned the nature of art vs. artifact, Vo’s stance on copyright and ownership, the importance or possibility of intrinsic meaning in individual artworks, and how these meanings transform over time. These were legitimate concerns, since one of the pieces in Uterus featured a portrait of Vo’s nephew; another was a casting of his mother’s jawbone. Flanking the entrance to the exhibit was a collection of letters written by Henry Kissinger to Leonard Lyons in the ‘70s, framed and mounted on the wall with no modifications or explanation.

Though he was prodded, Vo didn’t budge. Instead, he provided cryptic, one-sentence answers to questions that begged several minutes of open discussion. Throughout the talk, it was impossible to tell whether Vo was innocent or if he was keeping the crowd in the dark about the nature of his exhibit. Was he one step ahead of everybody the whole time, or had he not noticed elements of his art that were glaringly obvious to everyone else?

Perhaps Vo’s unwillingness to explain his exhibit in any formal way points more to Uterus’ self-conscious lack of cohesion than to the artist’s aura of uneasiness. The works included aren’t supposed to connect, but are meant to be observed individually. Vo mentioned in the interview that he coined the show’s title before knowing what he wanted it to include. Furthermore, when patterns emerged in the work he selected to show, he axed the emerging trend and started over.

When the gallery isn’t filled with distinguished guests and those who are there to listen to them, the bareness of the physical space is immediately apparent. Around half a dozen works are allotted the entirety of the gallery space. A six-piece display in a room seems normal when considering the large-scale canvases of artists like Pollock or Rubens, but Vo’s pieces are all tiny, colorless and self-contained. The positioning of the artwork emphasizes the slightness of form: most pieces are assigned to corners of the gallery. An old milk crate, narrow white shelves that bleed into the pasty coloring of the room, and a bay window structure contain the separate works in their unique worlds.

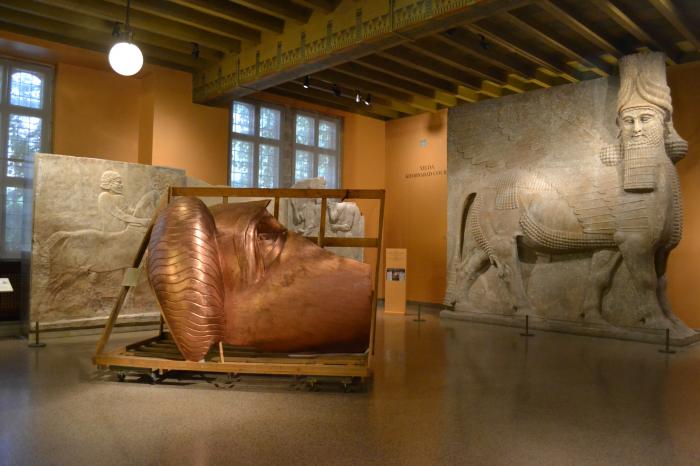

In contrast to the self-alienating pieces that constitute Uterus, Vo’s other project We the People is a violent splintering and destabilizing of an iconic whole. This sculpture-based installation is a life-size bronze replica of the Statue of Liberty split into four hundred pieces and dispersed throughout some fifteen cities worldwide. Alongside the opening of Uterus, five of these pieces were also placed on campus: two included in the Oriental Institute’s museum gallery space, two located in the Law School quadrangle, and the other placed adjacent to the Booth School of Business.

Save for the piece placed immediately in front of the Institute’s hippogriff-like Lamassu figure, which is very apparently a section of Lady Liberty’s face, the four other detail works scattered around campus are of fairly unremarkable portions of the original statue. Sheets of her clothing, when broken down into segments and viewed in isolation from one another, lose any visual connection to the sculpture they are modeled upon. Due to their highly abstracted appearance, these fan-like slabs of metal pull the meaning of the original statue into further obscurity.

Despite Vo’s refusal to entertain the development of a pattern, and his obsessive desire to treat objects at face value, the syncretism between We the People and Uterus is undeniable. We the People presents a single statue split into hundreds of abstract pieces that only gain meaning when understood collectively. Conversely, the significance of Uterus, as its name might suggest, is entirely self-contained: each object has its own unique significance that is irrelevant to that of all others in the show. Somehow, through the muddle and the mystery surrounding them, these two exhibits of completely opposite scale and ambition end up complimenting each other through their alternate understandings of meaning. Whether or not this was Vo’s secret plan all along is probably something he will never tell us.