It seems that we’re still obsessed with the divide between the Orient and the Occident—a divide created by centuries of people on both sides of the globe who made claims about differences in art, culture, and political views between these two ways of being. The recent exhibit at the Smart Museum of Art, Awash in Color: French and Japanese Prints, tries to make its own claims about the relationship between East and West.

The exhibit occupies one large area of the museum and is divided among several galleries. It presents both chronologically and stylistically a series of prints from the two countries. These are contrasted with additional prints from America. Most of the prints were created by well-known artists, although this fame is relative depending on one’s cultural vantage point—while names like Manet and Cassatt may ring a bell in the West, printmakers like Hokusai and Masanobu, mainstays of Japanese art, won’t inspire the same sense of familiarity.

For the most part, French and Japanese pieces are kept separate. Traditional French prints from the advent of etching and aquatint in the 1780s snake along the wall, their chiaroscuro effects painstakingly rendered in the figures and scenes. The meticulousness of the French technique continues with examples from Manet, who is usually better known for his paintings. Though Manet’s prints are fairly obscure, he produces the same color-blocking effect in them as in his paintings, so that the difference between the two genres is hardly noticeable. Only the prints of French artist Anne Allen show Eastern influence: the human figures are rendered more flat than the preferred three-dimensional effect of his compatriots.

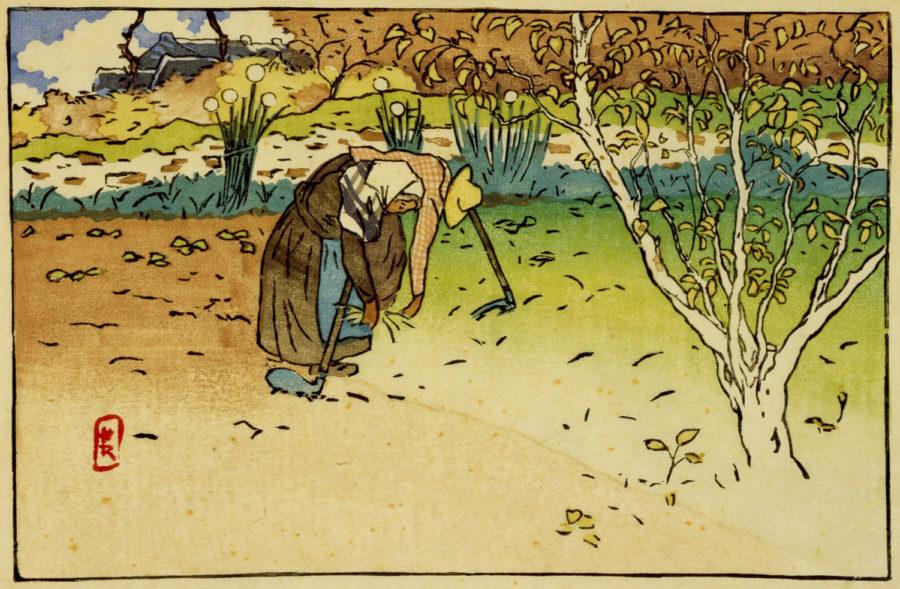

The Japanese prints on the opposite wall are different. As the informational placards throughout the exhibit are eager to convey, printmaking in Japan was a confluence of “high” and “low” art. The subjects of the pieces vary widely from members of the Imperial family to prostitutes. Masanobu’s mid-18th century works depict summer rainstorms in which the colorless, two-dimensional women struggle to keep their kimonos from falling off their breasts. All Masanobu’s subjects are presented with the same meticulousness that marked the French artists’ scenes of proper luncheons.

The prints were divided according to the nationality of the artists. Some of the most engaging works were those created out of the influence of one culture on another. This type of influence was felt in the Japanese “Berlin blue” prints and French seascapes. Hokusai’s famous “36 Views of Mt. Fuji,” printed in exquisite hues to evoke weightlessness, sit beside the comparatively blocky and awkward efforts of French printmakers like Henri Rivière. Rivière, who attempted Japanese techniques of multiple perspectives and striking contrasts, even signed his pieces in a style that evoked Japanese characters, with his initials stamped vertically in a red rectangle. Rivière’s imitation comes off as vaguely disrespectful. One gets the impression of a Westerner fascinated more by the foreignness of the Japanese prints than by the skill involved.

The French influence on Japanese prints is presented through the juxtaposition of flower prints by Pierre-Joseph Redoute and Katsushika Hokusai’s attempts at depicting the same subject. Unlike the French prints in the Japanese style, the two artists’ renderings are dramatically different. Hokusai does not give up the Japanese preference for shadowless, flat figures even in his “French-style” flowers, so that his works are reminiscent of Ellsworth Kelly’s plant drawings.

In one print by Chikanobu, “The Illustrious Nobility of the Empire,” figures blend into a flattened-out background. The members of the Imperial family of Japan are presented as Western figures of decadence. The Emperor and his wife and children wear Western-style clothing, garish in contrast to their ancestral garb. Their faces look almost greedy. This impression may have been exacerbated by the way the subjects are presented—they are surrounded by wealth and garbed in fine fabric. France may have jumped at the influx of Japanese art and influence, but the people of Japan did not accept the West’s influence with open arms. This is best shown in the Japanese artists’ faithfulness to their style; they rarely attempt to reproduce Western art the way the Europeans copied the Japanese. Worlds collided, but not equally, and the Smart’s exhibit suggests that Western culture may have borrowed more than it gave back.