When the pharmaceutical heiress Ruth Lilly died in 2002, she left a $200 million bequest to Poetry magazine. After a nearly century-long struggle to get by, the magazine suddenly found itself fending off critics who felt it had been given too much and the rest of the humanities too little. Today Poetry includes the Poetry Foundation, which has its monolithic headquarters downtown.

But the real life force of the magazine has always been its contributors, not its contributions. It has given voice to poets celebrated and unknown; it has printed probing inquiries and private reflections; it has invited discourse and inspired movements. “The Open Door will be the policy of this magazine,” wrote Poetry founder Harriet Monroe in 1912. “May the great poet we are looking for never find it shut, or half-shut, against his ample genius!”

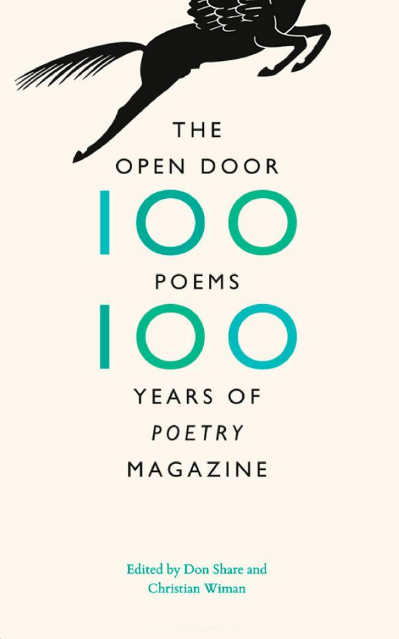

As Poetry observes its centennial year, it has sought to “celebrate poetry, not Poetry.” That’s how editor Christian Wiman phrases it in his introduction to the magazine’s commemorative anthology, The Open Door: One Hundred Poems, One Hundred Years of Poetry Magazine (University of Chicago Press). The book is not meant to be a “best of” compilation, like some anthologies. Instead, Wiman and Poetry Senior Editor Don Share selected poems that, over the course of a century, have simply stood out. “Every poem in this book,” Wiman writes, “[falls on the] spectrum between life and learning, between linguistic powers…and the messy living reality out of which all language, if it would stay alive, must be rooted.” Beyond that, the poems of The Open Door find more unity in their distinctive imaginative power than anything else.

The first word goes to Pound (“In a Station of the Metro”), and the last word to Yeats (“The Fisherman”), but in between we get Laura Kasischke after T.S. Eliot, and Jacob Saenz before Langston Hughes. Short quips of prose from the magazine and its letters provide a rough contextual frame, but mostly the reader is left to wander and discover, and the poems are left to speak for themselves. There is just enough surprise to expose our minds to others’ worlds, but not so much that we lose a sense of who we are.

To supplement the book, the foundation has opened a gallery exhibition featuring original photographs of its contributors. Every contributor to Poetry is asked to complete a thorough questionnaire and submit a photograph. No one at the magazine knows exactly when, or even why, this practice began (though Monroe herself was known for being thorough). But they’ve held onto the files, and over the years thousands of contributor bios have accumulated in the Poetry offices. Many capture poets at the onset of their careers, before their future successes or descents into obscurity (the file of a young Sylvia Plath, for instance, describes her summer plans for touring Europe by motorbike).

The exhibit itself is rather modest, comprising only six small glass display cases. Yet the photographs themselves can be stirring in their insights. There is no guideline for what contributors can submit, and they have responded with appropriate ingenuity; there are poets posing and poets writing, but also poets drinking, exploring, and standing shirtless—not to mention a stuffed rabbit and a dog.

As with the poems of the anthology, the photos resist paraphrase. Their impressions are enough. Gary Snyder squints intently into the camera, standing in the luminous outdoors; James Merrill leans back indifferently in a chair, lips parsed; Robert Frost sits in pensive silence, inside a departing train. One photo, mounted hastily on blue card stock, comes with a scrawling question: “Can you use this?”

In today’s literary scene, it’s become somewhat vogue to question whether poetry itself can still be effectively used. But in placing its focus on the poems and poets that have made the magazine what it is, Poetry has proven that there is still much to be had and said. There are lives behind this “seemingly unkillable magazine”—lives with plenty to say about our own.

Poet Photos: From the archives of Poetry magazine. At the Poetry Foundation, through November 29.