Today, only a few dozen Jews live in Sighet, Romania, a small town on the southern bank of the Tisza River, which separates Romania from Ukraine to the north. But this was not always so. In 1944, Hungary, of which Sighet was then a part, contained the last major European community unscathed by the Nazi Holocaust. However, in March 1944, Germany occupied Hungary and invested much energy in transporting its Jewish population of over half a million to concentration camps and death factories to the north—even at great expense to the stalling German war effort. From Sighet alone, 15 to 20 thousand Jews perished.

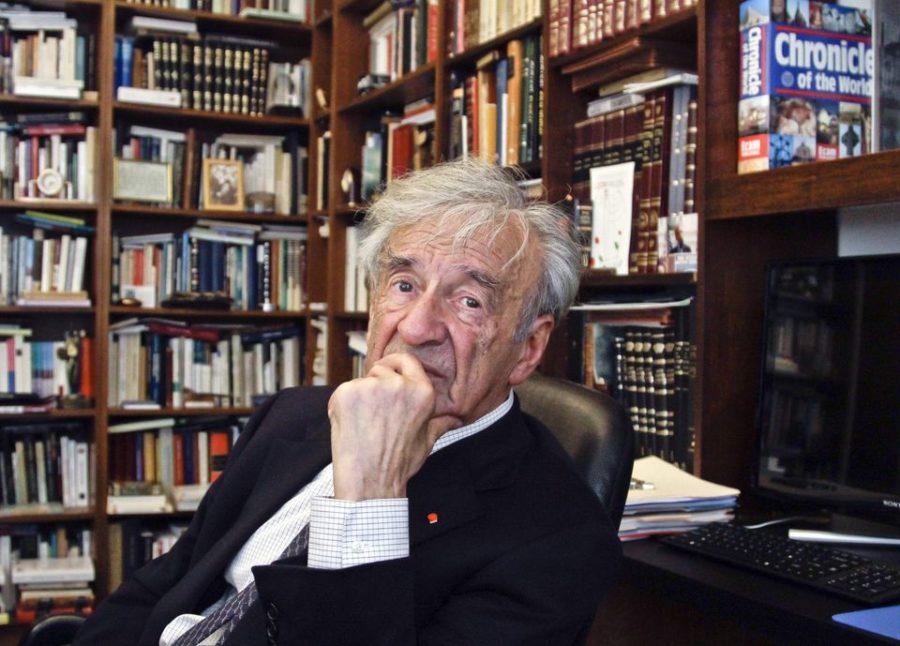

Among these late deportations was a 15-year-old boy whose name is now known around the world: Elie Wiesel. Winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986, Wiesel went on to earn numerous awards for his literary and humanitarian efforts and has authored more than 40 books, including Night.

This past Sunday, an 84-year-old Wiesel reflected on his experience in the Holocaust and his postwar literary and humanitarian career, occasioned by his receiving the 2012 Chicago Tribune Literary Prize to a packed Symphony Center. Though he is only one of thousands of Jews who survived the Holocaust, Wiesel was among the first to write about his experience in the concentration camps Auschwitz and Buchenwald, including the death of his mother, father, and sister, at a time when most survivors preferred to pass over the subject in silence. He wrote an 800-page account of his experience in the camps in 1958 by the title And the World Remained Silent, which was translated from the original Yiddish into French and, ultimately, English by the title Night in 1960. It’s hard to believe today, but Wiesel’s manuscript was rejected by several publishers who claimed “the subject [of the Holocaust] was morbid and interested no one.” When initially published, the book sold poorly. Starting in the ’70s, the book gained wide readership and sold over six million copies after being picked up by Oprah’s book club. It is now required reading in many American schools.

Asked to reflect on his childhood in Hungary, Wiesel said that he remembered himself always having a book in his hands from as early as age five. “It’s part of Jewish culture,” he said. “The book is a sacred object, and not just in the faith tradition, but as part of the human quest for meaning.” Wiesel began writing religious and philosophical essays at an early age alongside his precocious studies of the Talmud and the tradition of Jewish mysticism. Wiesel characterized his love for books and learning as deeply personal, rather than just academic or religious. “Books gave me warmth,” he said.

Wiesel’s personal attachment to books still rings clear today in his defense of the education and ethics around the world. In Night, Wiesel talks of a man called Moshe the Beadle from his town who miraculously escaped a prior deportation and came back to warn the Jews of Sighet about their fate and to urge them to escape. “Nobody listened,” Wiesel lamented. “I alone was there to hear him, and even I didn’t believe him. Who could believe such atrocities?” After surviving the camps, Wiesel carried on Moshe’s message and made his literary and humanitarian mission one of testifying the Holocaust to young people who are generations removed from its crimes.

After being liberated from Buchenwald by American troops on April 11, 1945, Wiesel immigrated to France, where he worked as a human rights journalist and began writing memoirs and fiction alongside his reporting. Astounded by the crimes he had witnessed, he embarked on a mission to understand how the Holocaust was largely the product of—as he would later learn—highly educated German men. “I am still baffled… It all seemed impossible to me. How could somebody who knows how to see the beauty in a Goethe poem be so susceptible to evil?” After a lifetime of investigating the question, Wiesel concluded that “these men may have had philosophy courses, but they didn’t have ethics.” One of Wiesel’s goals has since been encouraging universities to add ethics requirements for their students, including Boston University, where he is Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the humanities and a professor of philosophy and religion.

When asked why he didn’t respond to the catastrophe with vengeful thoughts and actions, as many of those who suffered under the Nazi regime did, Wiesel noted that his Jewish faith was renewed after the Holocaust. “That is not the Jewish way,” he said. “My response to the tragedy was books.” Noting that still other victims responded with silence, preferring to “turn the page” to their new lives in America or Israel, Wiesel insisted upon the power of writing and books for memory, which he called “the single theme that underlies all my work.”

In response to a question from a man in the audience, Wiesel confirmed a recent rumor that he will be co-authoring a book with President Obama, who has written three books and heard Wiesel speak at Occidental College in California when he was an undergraduate there. Though he wouldn’t reveal the book’s subject, it is bound to reflect the compassionate message he gives to young people today. “Be open to learning,” he said. “And listen to the other, whoever the other is. Listen and remember.”