For some reason, Jewish comedy lends itself very well to jokes involving food. It is hard to determine whether this indicates pathetic frivolity or whether it is simply too wonderful for words—probably, it is both. Take, for example, a joke from the opening monologue of Annie Hall, which, out of deference to Woody Allen, I will paraphrase. Two women are having lunch in the Catskills. One comments that the food is terrible; the other agrees and adds that the portions are upsettingly small. This, he proclaims, is exactly how he feels about life, “full of loneliness, and misery, and suffering, and unhappiness, and it’s all over much too quickly.”

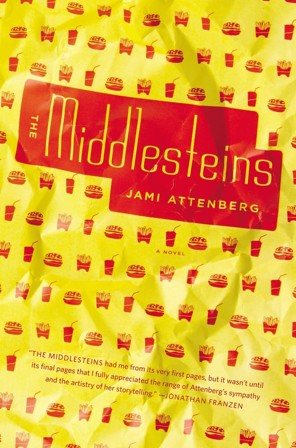

Jami Attenberg’s new novel The Middlesteins adds something special to this tradition of tragicomic consumption, yet her setup is notably different from Allen’s. It is a matter of portions—instead of ingesting too little, her characters often partake in far too many gustatory pleasures. Specifically, too many Big Macs, McRib sandwiches, Diet Cokes and apple pies the size of pocket protectors.

At the beginning of the novel we find Edie Middlestein weighing in at just under 250 pounds, couched in her modern-day suburban Chicago house, preparing for her second diabetes-related surgery on the same leg. We get a bit of her back-story—in the ’70s she was an overweight child living in a household that worshipped Golda Meir and Coca Cola in the same breath. Naturally intelligent and fiery, she went to law school, where she met her future husband, Richard Middlestein, the owner of a local pharmacy, with whom she had two children.

The book is a bit of jumble at first as it flits around in time and switches perspective every few pages from Edie to Richard to their sour daughter Robin, always in third-person omniscient. The descriptions we get of these characters often feel like little more than bits of raw data, which nobody would find funny unless they knew someone exactly like one of these people. For example, Robin, coming off a sullen childhood in Chicagoland, lives in Brooklyn for two hellish years with three other roommates (Jennifer, Julie, and Jordan) who are doing Teach for America and described as such: “all Jewish, they all had gone to Midwestern colleges, and they all had individual joint bank accounts with their mothers.” This sort of detour into the self-deprecating inside joke comes off as disingenuous at first, probably because the novel lacks focus.

However, the main dish, and certainly the most complex, is Edie, who, as everyone in the family knows, is slowly killing herself with a diet of fast food and greasy Chinese takeout. As the book progresses, her family begins to mobilize around her in an effort to stop her from eating herself to death. Then, in the midst of this family crisis, Richard, previously understood to be the passive, supportive husband, walks out on his wife. He takes up with a British expat named Beverley who, at fifty-something, still has naturally red hair (or so he believes).

The plot gains steam as we become more entangled in the lives of Edie and Richard’s son Benny and his wife Rachelle, who starts obsessively following her mother-in-law through a maze of McDonald’s and Burger King drive-throughs. Rachelle is razor-thin, always appropriately dressed, and gets all tense around the mouth when her waiter leaves croutons on her salad after having expressly been asked not to. On top of her busy schedule of being a voyeuristic desperate housewife, she is planning a So You Think You Can Dance–themed B’nai Mitzvah for her twins, which turns out to be the setting of the most hilarious scene in the book. Meanwhile, Benny loses most of his hair due to stress, occasionally pleads with his wife to be less uptight, smokes a lot of weed in his backyard, and generally resembles a slightly younger Lester Burnham who never gets his groove back.

By the end of the book, though, the familial panorama of quirky details and cheap laughs gives way to a series of melancholy events, the weakening of some relationships, and the strengthening of others. Though seeped in tragedy, the end of the novel is fundamentally ambivalent. Attenberg tells us breezily what befalls the Middlesteins after her novel’s close, and then everyone sort of hangs their heads, graciously bows, and takes leave of the story. Her tale isn’t cautionary and it’s not a cop-out. In fact, after all of the crying and kvetching, there doesn’t seem to be anything remarkable about it. However, the book is much better off for its honest depiction of ambiguity, even in heavy moments.

Attenberg’s novel can be flippant at times, and full of shallow hyperbole at others (all of the family members think to themselves, “She’s going to die,” all the time, without prompting). But as the story progresses it becomes clear that, like the joke about the women at the Catskills resort, The Middlesteins is a weighty story told in small portions. Life eats away at each of its characters slowly, but also sweetly, and the characters find much to relish in their dysfunctional suburban setup.