“Cold Pastoral,” Marina Keegan

Marina Keegan, the young writer who tragically died days after her graduation from Yale University last spring, isn’t even the saddest part of this story. Previously unpublished until The New Yorker posted it online this past October, “Cold Pastoral” is a short story told from the perspective of a girl whose sorta-hookup has just died. She tries to navigate her way among numbness, grief, and the emotions that come with being someone’s not-really girlfriend, as well as having awkward encounters with his parents and ex-girlfriend (with whom he was still in love). In addition to a harrowing plot, Keegan uncannily captures the limbo of those not-quite relationships we’re all familiar with: “I think we took a certain pride in our ambiguity. As if the tribulations of it all were somehow beneath us. Secretly, of course, the pauses in our correspondence were as calculated as our casualness—and we’d wait for those drunken moments when we might admit a ‘hey,’ pause, ‘I like you.’”

NW, Zadie Smith

Though NW, Zadie Smith’s much-awaited fourth novel, received mixed reviews, it still crept its way into the few best-of lists that have already come out (like The New York Times’s “Top 10 Books of the Year”). This is due, I think, to the fact that it is not at all like her much-touted debut novel White Teeth, which was published when she was 25—and this is both a good and bad thing.

NW starts slowly. Split into five sections, each roughly following a different character, time period, or using a different style, the novel opens with a chance interaction between Leah and another woman in Willesden, a northwest neighborhood of London. The random interaction leads to paranoia, death, and a dramatic scene outside a drug store. From here we get mercurial leaps and bounds from one Londoner to another, regardless of their connections. Even though NW didn’t quite come together, it was engaging and promising enough that you couldn’t mind that it was less than perfect. In the end, I don’t know what’s more surprising, the uncanny ending or the fact that a novel of NW’s caliber doesn’t even have its own Wikipedia page yet.

“Permission to Enter,” Zadie Smith

This pick may or may not be an excuse to talk about Zadie Smith some more. Published in the July 30 edition of The New Yorker, “Permission to Enter” is actually a snippet from NW. With part of the story structured as the responses of two girls (Leah and Natalie) to unknown questions, the story shows their divergent paths as they grow up and out of their London school. Easily the strongest and most engaging part of NW, this section makes us care about Leah’s numb life, Natalie’s strange psychology, and how these characters can all relate to one another in a meaningful way.

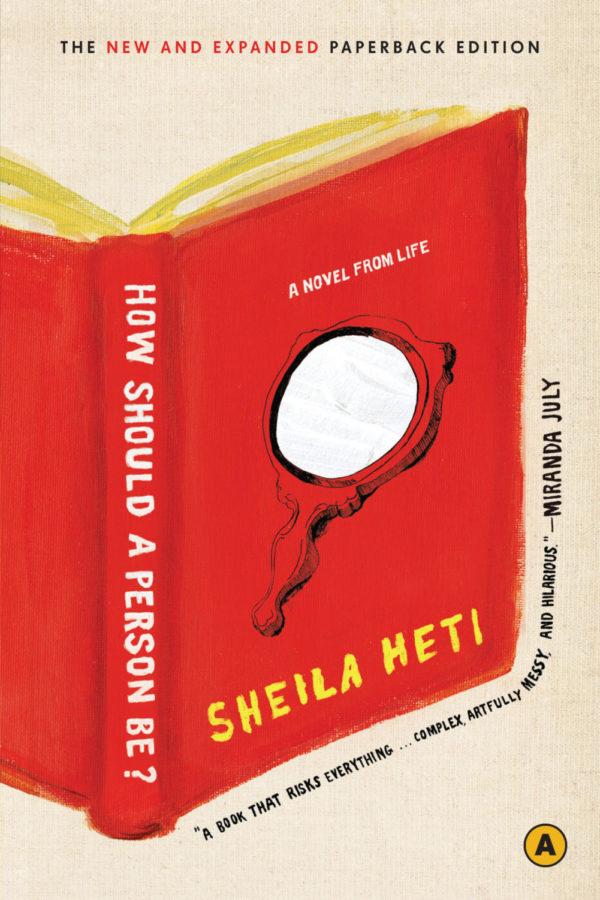

How Should a Person Be?, Sheila Heti

Canadian writer Sheila Heti’s novel is a spin on recent events in Heti’s life—her divorce, friendship with the painter Margaux Williamson, and eventual writing of the book itself. Aside from the fact that it’s almost an entirely autobiographical novel, HSAPB is notable because of its focus on the ugly, obsessive, and embarrassing parts of Heti’s life. The underlying current isn’t so different from that of HBO’s Girls. Take out the parental dependence, add in a failed marriage, keep the e-mails and awkward sex. What was so interesting was that this same woman—who writes about getting fired from a beauty salon and drinking for eight hours straight—is also the author of four books, and has written for n+1, The Guardian, and The New York Times. And these intense differences between personal and professional life aren’t irreconcilable, paradoxical, or abnormal—they’re just not talked about, or, really, separate at all.

Three Strong Women, Marie NDiaye

Before you even learn that much about the book itself, you know it has a lot going for it. Three Strong Women earned its French-Senegalese author Marie NDiaye the prestigious Prix Goncourt—the first time it’s ever been won by a black woman. NDiaye also co-wrote the screenplay for Claire Denis’s 2009 White Material, which won the coveted Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival. As if her credentials weren’t enough, there’s the allure of the book itself. Despite its title, Three Strong Women avoids the pitfalls of didacticism and sentimentality. The women portrayed in the novel’s three sections are rooted in specificity and a sense of reality so that their stories evade bland, inconclusive and pointless sadness.