A mother and her son walk hand in hand. How could such an inconsequential act bear such heavy burdens? The boy wonders why can’t see the car yet. But his mother, consumed with details like the appearance of motherhood, releases his grasp (or does he release hers?). And soon he is gone.

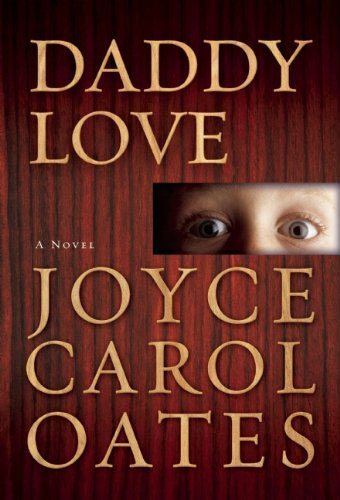

Joyce Carol Oates’ latest novel, Daddy Love, is the wrenching and disturbing tale of a five-year-old, Robbie Whitcomb, who is abducted from a mall parking lot and forced into abusive captivity. Taken from his mother, Dinah, in a moment, Robbie is lost for six years. Dinah’s desperate attempts to chase his attacker render her brutally and permanently disfigured by the kidnapper, Chester Cash, also known as Daddy Love. He is a serial killer, a pedophile, and a master in the art of deception. He torments the boy, who is now called Gideon Cash, into both physical and psychological submission.

It is natural to demand what purpose Oates’ particularly painful brand of storytelling serves, though she is known for her forays into the heavy and twisted. It may be precisely due to her need to tackle the extents of human potential—to bring the inner perspective to a vantage point that is frighteningly grounded in reality—that she has penned this novel. But Daddy Love verges on being too distressing. The book is at once a depiction of the depths of cruelty and the heights of hope. While it succeeds in evoking the reader’s emotions, the story wants for elaboration and exploration on several fronts.

The novel’s strength lies in its intimate understanding of human motivation: how the individual thinks and reacts. This establishes a palpable connection between character and audience. The story unfolds through various perspectives, allowing for a range of language poetic and powerful in its simplicity and direct in its insight. One is not a witness to but a participant in a script of human thought, emotion, and interaction: The desperation of a mother in critical condition and of a stricken father at her bedside, searching for their son, is moving. And yet, when Preacher Cash (as Daddy Love disguises himself) delivers a sermon, the aura of the biblical intermingles with the tongue of evil. The sermon is a sickening display of religion rendered completely hypocritical when expressed in the voice of a psychopath. At times the novel shocks with a line or an idea so gripping that one must halt and wonder: How much is there beneath the surface that we do not detect?

“Our memories goad us to repeat the past, when we’d been happy,” writes Oates. “Even as we know that the past is past, and we will not be happy.”

Yet the story lacks the development necessary to convincingly portray the magnitude of its undertaking. In giving voice to the abductor-abductee mentalities of Daddy Love and Gideon, the narrative is unrestrained; the former ruminates on his warped and perverted machinations and likens them to divine purpose, while the latter thrives on Daddy Love’s approval but hates him profoundly. The questions remain: Why does Gideon not attempt escape sooner? Why does he not seek help, silently enduring years of torture? The psychoanalysis that would provide answers to the crux of the story is scarcely glimpsed. When it comes to Daddy Love and Gideon, the narrative becomes a horror story–type depiction instead of a psychological exploration. Oates’ point may well be that one cannot understand such a devastating situation without experiencing it. Once Dinah and Gideon are reunited, Dinah’s thoughts impart this idea. Still, the novel lacks the progression necessary to convincingly communicate this message.

The Whitcombs’ character development is trite and too cliché to redeem the dark undertones of the narrative’s main thrust. The superficiality of the investigation into their trauma leaves much to be desired. Dinah’s husband Whit is the spiraling, adulterous husband who simultaneously contemplates leaving his wife and proclaims his familial affection for her. Dinah plays the archetypal survivor with undying devotion, walking without a much-needed cane, braving the grimaces of a world too enamored with appearance and too laden with artificial pity to appreciate the toil of her efforts. However, her desperate longing for her son—her “mommy love”—gives her depth.

On the whole, Daddy Love lacks resolution. It skips from 2006 to 2012 without explanation, and the concluding chapters falter to an abrupt end. It is conveyed unsatisfactorily. The ending not only waxes irresolute, but also shatters any hope of safety. After Robbie is returned, what remains is the telltale acknowledgement that six years have been utterly stripped from the Whitcomb family—“a part of their souls,” writes Oates—with relationships left in a state beyond repair.