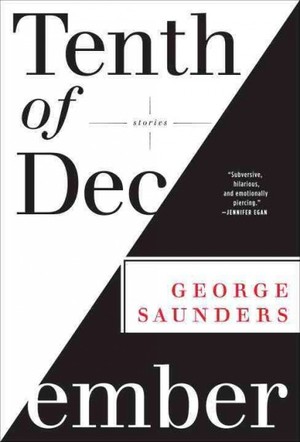

Before you read George Saunders’ new short story collection, Tenth of December, you should read a profile of Saunders recently published in The New York Times Magazine, “George Saunders Has Written the Best Book You’ll Read This Year.” You will learn certain facts: Saunders is in approximately the same generational cohort of fiction writers as Jonathan Franzen and David Foster Wallace—to wit, he’s firmly rooted in postmodernism; Saunders published his first collection, CivilWarLand in Bad Decline (1996), at age 37, having written the stories while working a day job preparing technical reports in Rochester; Saunders’ work has a strong interest in the dehumanizing effects of capital, something he picked up on through jobs (roofing, for example) he held earlier in his adult life.

You may also see a picture accompanying the Times profile that shows a young Saunders. The author of the piece, Joel Lovell, writes that Saunders is “playing a Fender Telecaster, with white-blond Johnny Winter hair to his shoulders. ‘In our lives, we’re many people,’ he said as he lifted the photo off the shelf.”

These are just a couple sentences from a lengthy profile, yet Saunders’ generous reaction to his young self is powerfully telling of how he writes. His stories are not flush with formal innovation, or humor, or straight-up satire, though they contain these things. They’re also not about ego. Saunders does make his presence felt in every story, but the collection is primarily rooted in a fascination with people. Each story is, at its core, a portrait of one, two, or a few characters. Often, he gently lays bare the plot of the story as if taking a blanket off a character. We see the characters’ best—or worst—selves, and the author’s respect for the messiness—life—that unfolds between the extremes of human behavior. People are worth loving, Saunders and his characters conclude, but rarely because things are simple.

Tenth of December is also an impressive collection in form and style. One story, “Sticks,” is barely a page long; another, “The Semplica Girl Diaries,” is the longest story in the book (60 pages). The story should have come earlier. It weighs down the middle section of what is otherwise a well-paced romp of a collection. “Exhortation” is a memorandum. “Home” has numbered sections. “Puppy,” a concise gaze into class issues, is told from more than one point of view (this isn’t exactly formal innovation, but it still exemplifies Saunders’ deep consideration for communicating the full human implications of his stories).

In “Victory Lap,” Saunders sounds like what he is, which is a middle-aged man writing the thoughts of a 14-year-old girl, but he also sounds totally right: “So ixnay on the local boys. A special ixnay on Matt Drey, owner of the largest mouth in the land. Kissing him last night at the pep rally had been like kissing an underpass.” “The Semplica Girl Diaries” is written in a kind of shorthand. The diarist is a middle-aged man, not a girl, and he writes, “Why were we put here, so inclined to love, when end of our story = death? That harsh. That cruel. Do not like.”

Saunders’ collection will continue to move you after you finish the book’s last/title story about a young boy who meets a cancer patient in the woods on a brutally cold day. It ends on a Saunders-ian, humanistic note, when the cancer patient, Donald Eber, sees his wife’s face clouded with worry for him. “He knew her so well… Overriding everything else in that lovely face was concern. She came to him now, stumbling a bit on a swell in the floor of this stranger’s house.”

After I finished Tenth of December, it was as if the space between those last two pages, the place where the spine is, was Saunders’ furrowed brow, calmly but firmly advising that I go into the world. I needed to leave my chair, maybe for a walk, maybe to go to Treasure Island, where the high concentration of old people is always refreshing. Half-snow was coming down. Later that night my roommates and I ended up at a party on the other side of the city. We were suddenly friends with the DJs; then we were the DJs. We introduced ourselves to everyone there, using a different name each time. The bathroom mirror of the small apartment, I found, was shattered, and the sconces had been torn from the walls. I saw corners of my reflection. In our lives, we’re many people. What more would the wise Saunders say about the situation I had gotten myself into? Why was I so perplexed, and so delighted, to be alive?