The 20th-century fiction writer Leonard Michaels’s book Sylvia is a fictionalized memoir—or a truth-based novel—about living with his mentally ill ex-wife, named Sylvia, in Greenwich Village in the 1960s. Rereading Sylvia recently, I was struck by how much I loved a passage Michaels quotes from his own journal entry about Sylvia and her similarly depraved friend Agatha: “‘They are even close in their looks—same height, same shape. I found them asleep together, on the living room couch, one black-haired girl, one blonde. The difference only showed how much they looked the same, two girls lying on the couch in late afternoon. They looked like words that rhyme.’”

The next day, I found myself noticing that the title of a short story I had read rhymed; then I began thinking the story’s main ideas, and main characters, “rhymed.” In her new genre-defying book Artful, Ali Smith reminds us that we’re always doing just this. We’re always synthesizing our personal, particular cultural references to create ideas about how art moves through us, and moves our lives forward.

Artful began as four lectures Smith delivered when she was a visiting professor at St. Anne’s College, Oxford (she’s Scottish). The lectures are simply titled, “On time,” “On form,” “On edge,” and “On offer and reflection.” They have numbered subtitles, some of which poke fun at the cute/clever academic title. (“Please Mr. Post Man, Look and See: Remembrance of Things Post.”) Yet Smith also seems committed to presenting Artful in an unpolished, artless way. She keeps some of the lectures’ subtitles in what appears to be their original drafts, like, “Haven’t Found a Song Title for This Section Yet/ something about linearity—maybe Time After Time or Everybody’s Got to Learn Sometime (By the Korgis—check lyrics).”

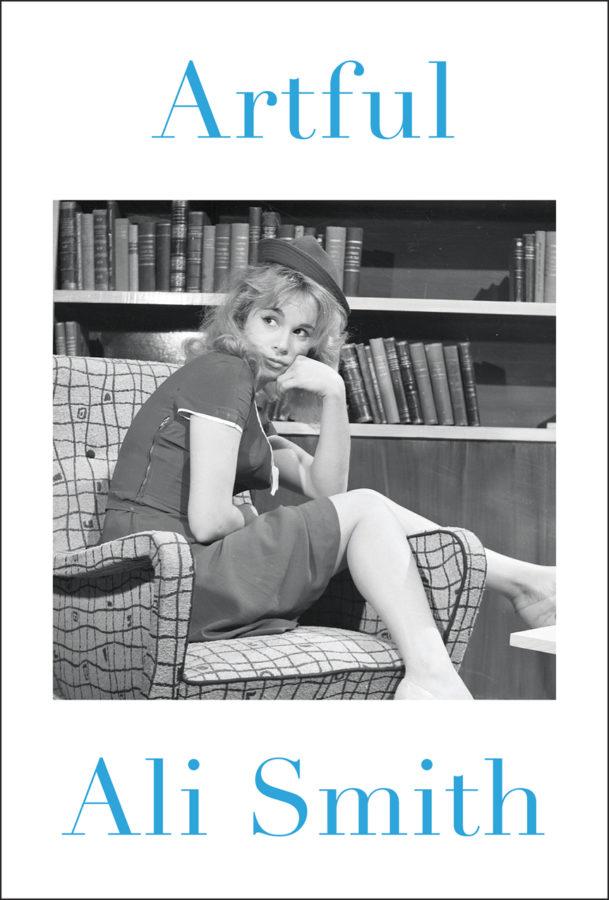

Sometimes this idea of Smith’s, that of the joint cultural/emotional touchstone that propels us, which is really the backbone—spine—of her book, aligns all neat, like in one plot thread that begins when the image of her dead lover speaks to her in what Smith believes are nonsense words. Smith recounts the words to a psychiatrist, who says they sound Greek; eventually the words lead her to the movies of Greek actress Aliki Vougiouklaki, who is featured on the book’s cover and comes to symbolize how connected Smith and her lover have remained.

Another cool synthesis comes when Smith sees the psychiatrist for the first time. The psychiatrist does a hokey visualization exercise, and instead of picturing herself in a movie theater during the exercise as she’s supposed to, Smith imagines having transcendent sex with her dead partner. Afterward, the psychiatrist asks her if the exercise was helpful and, in reference to a sexual metaphor she had been thinking of moments before, Smith replies, “‘It rang a bell with me somewhere, yes.’” It’s a poignant incident, one that supports the idea that we go through our days making a series of inside jokes with ourselves, so that what passes for interaction actually happens at the intersection between two people’s mutually indecipherable allusions.

Like amateur hip-hop choreography, though, the book stalls between its brilliant forward leaps. It’s obvious when Smith’s heart and full energies aren’t present, which happens when she tries to be academic. She is obviously not at home in heady prose, where her ideas are stimulating but vague. She gets into a weird abstraction and definition mode. Consider these sentences from “On edge”: “Edges are extremes. Edges are borders. Edges are very much about identity, about who you are.” In these disappointing, indecipherable passages, Smith never goes beyond the superficial notions to which her words gesture.

In an interview ten years ago with the writer Jeannette Winterson, Smith said she wants her books to stand upright on their own, without her promotion and authorly presence, since she “looks like a troll.” With this in mind, it feels important, for Smith’s sake, to seriously consider recasting the book’s elusive nature as intentional. Artful’s great power and great vulnerability lies in its refusal to be confined to one genre, or idea, or movement. It’s a novel about love and mourning; it’s a short story or essay collection about one person’s web of culture; it’s a cultural treatise about the relationship between art and us. To wit, Smith has written the crap out of Artful, with the result that it moves around so much it might not go anywhere. But what weakens the book’s trajectory in our eyes gives it uniqueness and character by Smith’s account—staying power, instead of direction.

The best advice for how to move through Artful comes from its own epigraph, several lines from a Bertolt Brecht play. “Don’t try to hold on to the wave/That’s breaking against your foot: so long as/You stand in the stream fresh waves/Will always keep breaking against it.”