There’s just one problem with holding an exhibition called Picasso and Chicago: The two never met. In fact, Picasso never even made it to America. But the Art Institute of Chicago confronts this little snag head on. When you enter the exhibit, the first thing you see is a written introduction on the wall—and the first thing it tells you is that Picasso never set foot in the Second City.

Of course, the second thing it tells you is that their relationship nevertheless “had a profound impact on both,” and this is where Picasso and Chicago stakes its claim. The exhibit celebrates the centennial of the 1913 Armory Show, a showcase of modern European art brought to America that was radical on this side of the pond. The AIC was the only museum to host the show, which, among nearly 650 works, featured seven paintings and drawings by Picasso.

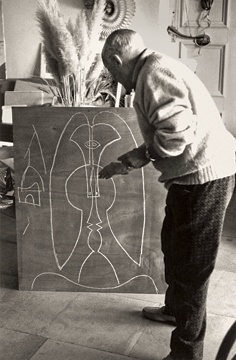

Years later, Chicago found itself begging Picasso to commission a piece for the city. The architects of the Daley Center offered him $100,000 for a public sculpture (he turned them down) and sent him classic Chicago memorabilia as “inspiration,” including a White Sox cap and a Bears jersey, once he’d agreed to work for free. They were a little late to the party, perhaps—the year of commissioning was 1963. But the way it happened still says more about Chicago than the artist himself: As the planning sketches show, Picasso had conceived of the work at least a year before Chicago even crossed his mind.

Profound is certainly one way of putting the sculpture’s impact on the city. Its unofficial moniker may be “Head of a Woman,” but its sinewy, industrial frame and jutting curvature have drawn comparisons to a sphinx, a baboon, and Picasso’s dog. It can seem foolish one minute and imposing the next.

Here, Picasso and Chicago does manage to pluck up a bona fide Chicagoan. Recordings of Studs Terkel provide the backdrop to a maquette of the Daley sculpture, with the incisive Terkel probing audiences at the 1967 unveiling with a simple yet irresolvable question: “What do you think?” If you ever run out of ways of saying “I don’t know,” you need only listen to Terkel’s interviews for a few fresh ideas. “I don’t think my opinion is so important,” one distressed woman admits. “I’m disappointed,” another concludes, her voice tinged with weary exasperation. The real relationship between Chicago and Picasso, it would seem, is one of a struggle to understand.

But if Picasso was radical in 1913 and controversial in 1963, in 2013 he is standard elite museum fare. And besides the Daley sculpture, which begins and ends the exhibit, the rest of Picasso and Chicago serves as a general examination of Picasso’s life work. Nearly everything has been selected from holdings around the city, as well as the AIC’s own collections, but that’s not on our minds as we traipse along.

But neither is a sense of disappointment. Picasso’s styles literally progress as the exhibit unfolds. We get a raw sense of the artist coming to be; we see Picasso working out what didn’t make sense to him.

After hearing from Terkel, a step into the next room immediately brings us back over 60 years in time. From the Picasso who was so renowned he was given sports attire he probably didn’t want, we are confronted with the Picasso who had to burn his own drawings to survive. We come face-to-face with “The Old Guitarist” (1903–4), that iconic depiction of an artist trapped in a milieu of dark blues, entranced in his music, bending over just to fit in his own lonely frame. Like Picasso, he’s never really there; he is real to us only through his art.

And there’s plenty of it to explore. We move chronologically, from the Blue Period to the Rose, from cubism to the art of the Spanish Civil War, and we see experiments in printmaking, sculpture, and classical themes along the way. At times it can get a bit overwhelming; you’ll wander into one room and wonder how you got there, your mind still stuck on a style from two rooms back.

But there are always moments of delight. Turn a corner and you’ll come across a Picasso you never even knew. There’s a tension between exuberance and its consequences in “Bacchic Scene with Minotaur,” one of the paper etchings of the “Vollard Suite” (1939); even while Bacchus basks with two women of classical bulge and classic Picasso disproportions, he shares a toast with the foreboding figure of the Minotaur. And there’s a palpable, uneasy sense of urgency to “Poems and Lithographs” (1949), Picasso’s own stream-of-consciousness poetry written (and later illustrated) while he lived in German-occupied Paris. Its letters are blotted, uneven, and rushed; they run into each other, unsure of themselves.

Picasso and Chicago is not really about Picasso and Chicago. But perhaps we simply need the semblance of a topic as an excuse to look at Picasso in an unadulterated light. And what that light reveals is a well nuanced portrait of the artist. Picasso, like his works themselves, resists interpretation. In this respect at least, he does bear one similarity to Chicago. As one man described the Daley sculpture to Terkel, “I think it’s a politician. It’s got so many faces, don’t you?”

Picasso and Chicago, The Art Institute of Chicago, through May 12