Last week’s Chicago mayoral debate was characterized by blizzard-induced late arrivals, race politics, and allegations regarding Rahm Emanuel’s loyalty to the Second City.

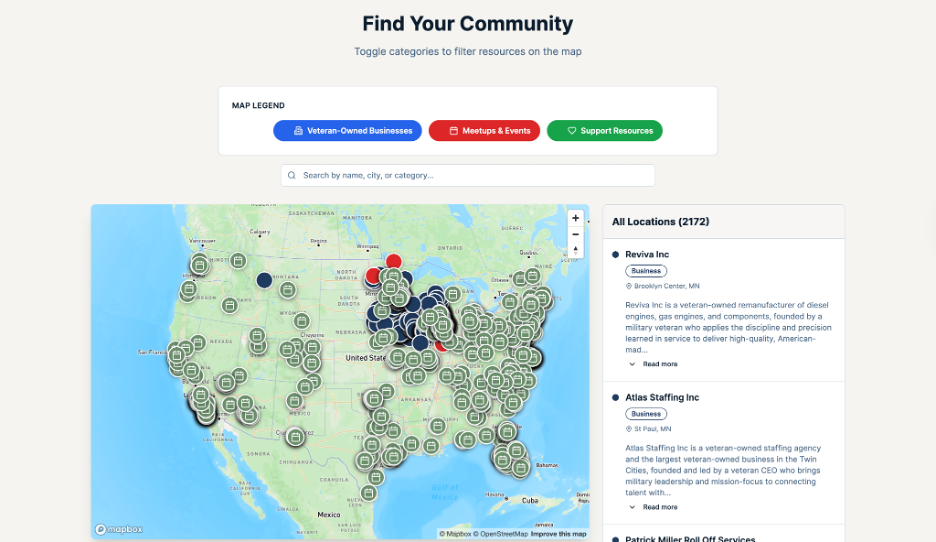

The candidates convened Wednesday at Hyde Park’s DuSable Museum of African American History in the campaign’s first debate to feature all six mayoral candidates. NBC 5 anchor Marion Jones facilitated the debate, while a panel of Chicago luminaries lobbed questions, ranging from how each candidate would tackle the city’s exploding deficit to how each would reduce the South Side’s staggering high school dropout rates.

Patricia van Pelt-Watkins, Gery Chico, and William “Dock” Walls all delivered their opening statements before the arrival of their competitors, Carol Moseley Braun, Miguel del Valle, and Rahm Emanuel arrived. Scheduling conflicts arose due to last week’s blizzard, which led to the original event’s cancellation.

Emanuel, who had been speaking at an LGBT forum, emerged from behind the curtain and leapt directly into his opening statement amid raucous applause, just as Watkins wrapped up her own opening address.

For Emanuel, however, the tone of the debate cooled as he answered questions. Despite the scattered attendees waving “Rahm for Mayor” placards, the catcalls and relative silence emanating from the audience after many of his responses created the impression that the former White House Chief of Staff was seen as an outsider.

The lukewarm reception turned to specific criticisms during a discussion on the misappropriation of tax increment financing (TIF), when Walls attacked Emanuel for working in the White House while there were “children dying in the streets in the city of Chicago.”

“You never came back and said that you wanted to bring more police officers to the city of Chicago,” Walls said. “You broke my heart, because you are a Chicagoan.”

Still, the debate remained civil for most of its run. The final question, on tackling the city deficit, drew specific answers with relatively little vitriol, though Chico took a moment to criticize Emanuel’s “tax-swap” proposal.

The proposal, which Chico has attacked in the past with televised ads, would lower the sales tax on most goods by a quarter of a percent in exchange for a 20 percent tax hike on services like limousine rentals and tanning salons.

Emanuel defended it as a hike on luxury services in order to spread the tax burden away from the “single mother who’s trying to get school supplies for her kid.”

The applause for Emanuel’s rebuttal quickly turned to mutters of disapproval when he suggested cutting the $500 million the city spends annually on employee healthcare by adopting a “comprehensive wellness plan” modeled on those of private companies.

Emanuel also cited the University’s Knapp Center for Biomedical Sciences, which opened in 2009, as the site of potential research into medicine and pharmaceuticals that might revitalize the city’s economy.

One attendee-requested question, regarding whether each candidate would support reparations for the descendants of black slaves, highlighted the racially-charged atmosphere that pervaded the debate. All six candidates declared that they would support such a measure, though Emanuel expressed reservations.

“We have to be honest and frank with ourselves. We have a budget deficit that also needs to be addressed. And that means… making tough decisions, it means investing in the areas that will lead to economic growth,” said Emanuel. The resulting murmurs among the audience elicited a call from facilitator Jones for decorum.

Opponent Watkins harangued Emanuel with a response that seemed to put him at odds with the entire auditorium.

“When I hear Rahm Emanuel talking about a budget deficit when we’re talking about reparations, to me, that’s offensive,” she said, increasing in volume as cheers continued to ring out from the predominately black audience. “This country was built on our backs. The backs of our ancestors. They bled, they died, they came in chains and they died in pain. So don’t talk to me about budget deficits right now.”

Walls also snubbed Emanuel’s point that reparations should come in the form of improved education, by countering that such measures would not provide justice to black senior citizens.

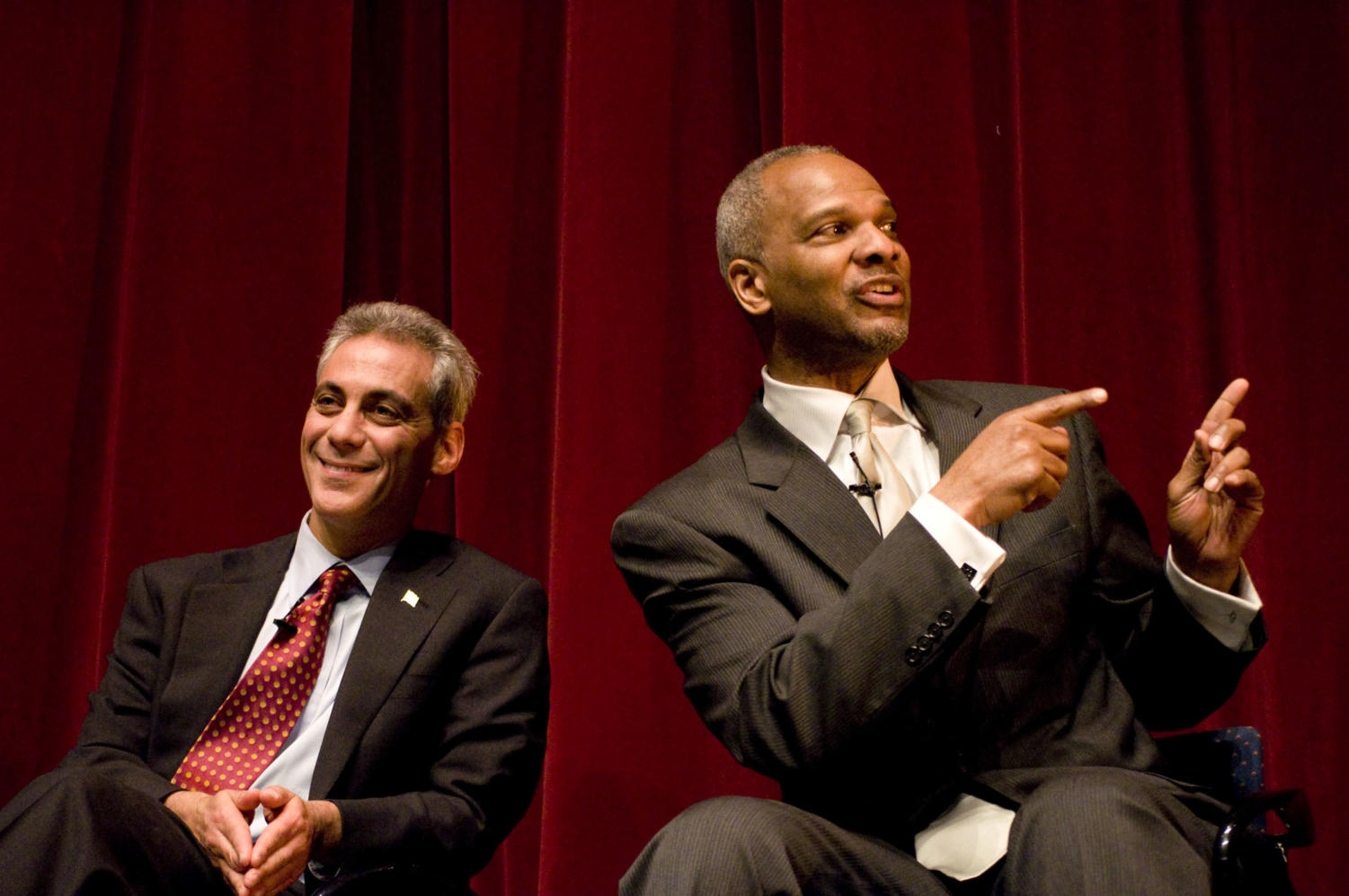

In another non-racial but heated exchange, Walls interrupted del Valle’s response with repeated prods for him to address the question more directly. Del Valle, who had just arrived and had not yet delivered his opening statement, focused on federally funded youth employment programs.

“What about reparations?” asked Walls. “In my mind, that’s reparations,” said del Valle, thrusting a finger toward Walls’s face.

Race politics emerged again as the candidates tackled a question about Chicago’s troubling recidivism rates, particularly among adult black males. Again, Emanuel garnered a cold response with his answer, which insisted that existing programs for probationary criminals needed to be publicized.

Chico pledged that he would prioritize the issue. He also said that he would force more accountability on employers who weren’t hiring ex-convicts, recounting the story of a felon he had met whom nobody would hire.

“The biggest problem we have is getting employers to step up and give people a chance,” he said. “You know, we’re a compassionate people. We have to give people second chances. Nobody’s perfect.”

“Everyone one of us has committed a crime in our lives,” Watkins added. “We just didn’t get caught.”

Braun chose to focus on the economic aspects of the question. “The best antipoverty program is a job. The best anticrime program is a job,” she said, citing small-scale employment programs, particularly those aimed toward youths, as being an effective way to cut recidivism rates.