In his latest work, David Sedaris takes readers on a snapshot journey through his life, from memories of his cluttered past to the present day. It is along this unconventional route—one which comes to span many continents, ranging from Raleigh, North Carolina’s south side to a taxidermist’s shop in England—that he offers reflections upon changing realities, both societal and personal, and ultimately provides insight into the very nature of what works to divide us while still holding us firmly together. In similar dualistic fashion, Let’s Explore Diabetes with Owls is teeming with a range of humor; Sedaris’s sharp wit is suffused with not a few jabs at himself. In all, this collection of essays forms an amusing commentary with substance.

Sedaris, it seems, has been a few places; the odd jobs he has accrued over the years, and more recently his writing career, have taken him around the world. Thus, his cultural awareness—his ability to intuitively understand the nuances of peoples’ actions within and removed from a certain context—shines as one of the strengths of the work, a telling reminder that not everyone sees us as we see ourselves. His reflections on often absurd European-American relations are witty, quietly troubling, and laced with mild indignation. “I could have written on frosting and still they’d have asked me about Guantanamo, and my country’s refusal to sign the Kyoto Accords,” he writes. His humor always balances out. Particularly entertaining is his explanation of the French reaction to Obama’s election in 2008: They were overjoyed that the Americans finally picked a candidate of whom they approved. His discussion of uniquely European idiosyncrasies is likely to resonate with an American audience, even if it does not necessarily agree with his liberal stance in general.

However, as the book continues, it is most notable for its sensitive, affected tone, which is still sarcastic and bitter. Here, Sedaris becomes less the comedian and more the world traveler with a message, and one worthy of attention. Most memorable in this sense is his discussion of a trip to China, and his experience of its standard of living. The result is a collection of striking thoughts wrapped up in ironic attire. “My trip reminded me that we are all just animals, that stuff comes out of every hole we have, no matter where we live or how much money we’ve got,” he remarks. “On some level we all know this and manage, quite pleasantly, to shove it toward the back of our minds.” He sometimes verges on the too real; an especially explicit rendering of a rooster being hacked to pieces before his very eyes is unappetizing. But worth it, nonetheless. For Sedaris, ever the animal lover, offsets these blunt forays with soft ventures into nature: His charming encounters with an Australian kookaburra (the “gym teacher” of the bird kingdom, according to Sedaris) and a sea turtle both showcase a perfectly lighthearted and quirky tone.

Yet he seems most at home discussing himself, especially his childhood. Indeed, his continual comparison between rearing practices from 50 years ago and today begets food for thought. However, this “me generation” argument is a little tired, and has been explored long enough for it to have lost some of its original salience. Having iterated it several times over, he seems to return to it more for comedic effect than anything else.

More thought-provoking, though, are the difficulties inherent in his family dynamics: an unsympathetic, demanding father; an accommodating, perhaps overly complacent, mother; and five rambunctious siblings—all under the guise of an ideal ’60s middle-class family. It begs the question: Can we ever really know who we are (or who we believe ourselves to be) when surrounded by others? When within a certain set of customs? Sedaris seems to have accepted his past, yet a certain haunting self-disapproval seems to linger throughout his essays, adding a definitively somber, modest tinge to his stories, and more fundamentally, to his characteristic humor—even, to an extent, defining it. It is within the tales of his childhood foibles and reveries that the story is most touching and nostalgic. The laughs he elicits are of a reminiscent flavor. Because those sweet memories are experienced in our youth, we shall never again return to them in just the same way.

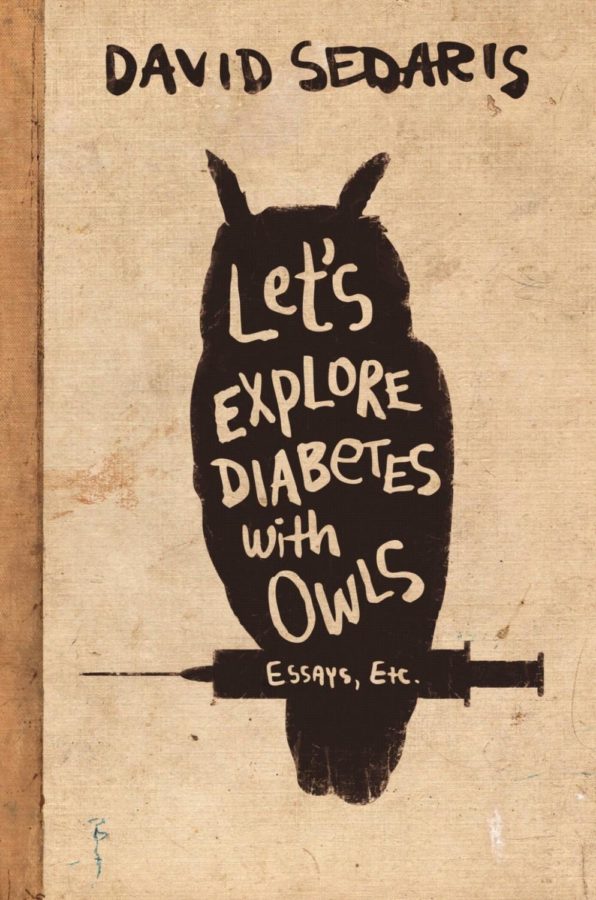

But why explore diabetes with owls? The secret is not divulged the way one would expect; there really is no explicit answer, but Sedaris hints at it throughout, in his own peculiar manner. He does know a thing or two about people, after all, and he seems to be counting on that knowledge for the answers to emerge. His charming autobiographical ruminations serve as foundations for the reader’s own introspective ventures.