In the wake of the 2008 recession, the liberal arts, and the humanities in particular, have had to defend their existence. Collectively, states are spending 10.8 percent less on higher education than they were five years ago, a cut which prompted Governor Rick Scott (R-FL) to suggest that his state’s public universities charge students more for “non-strategic majors.” Articles crop up ad infinitum in publications like the Chronicle of Higher Education defending the value of the humanities—and debating how to save them.

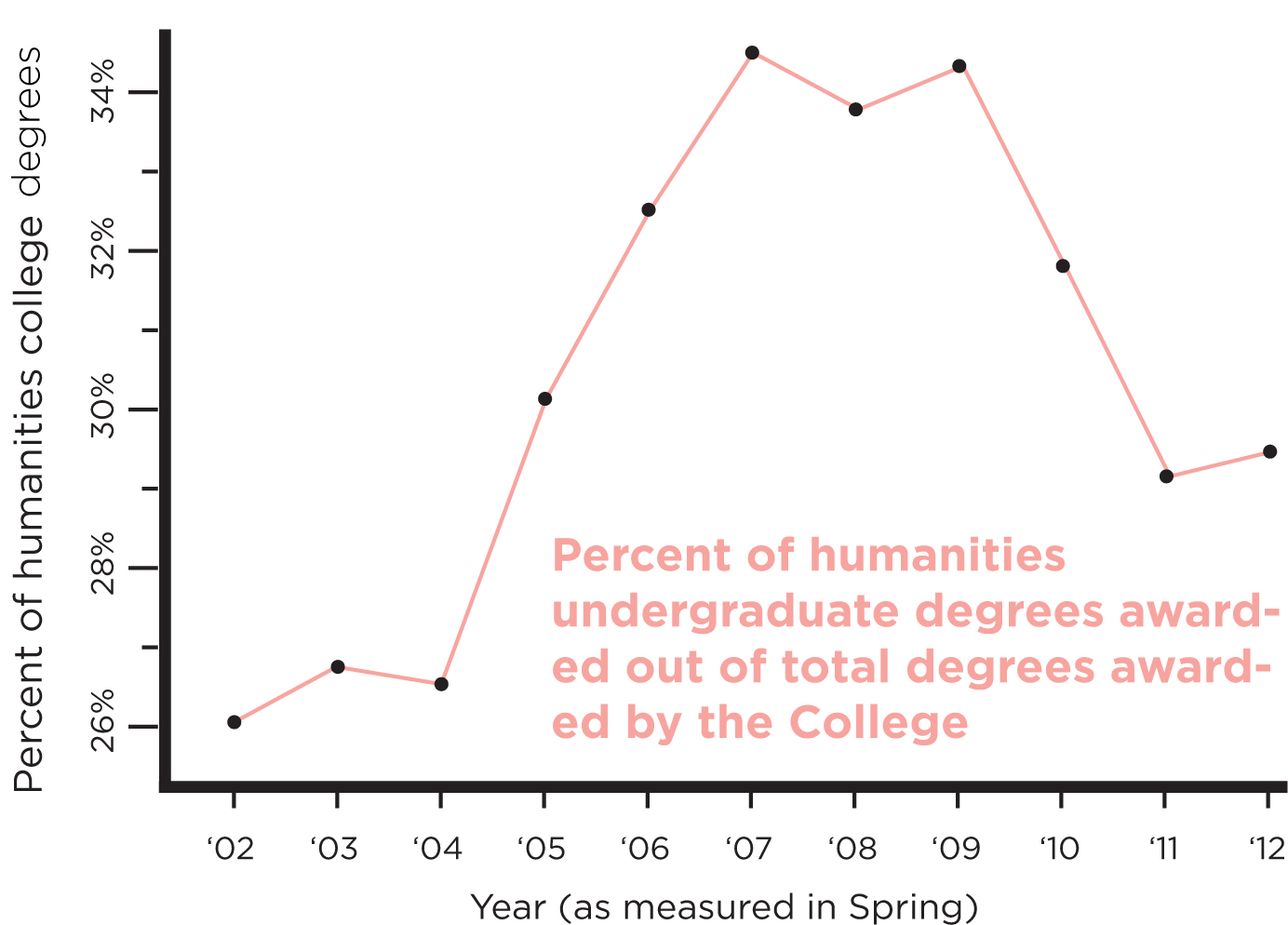

On one level, UChicago seems to have dodged existential questions of this kind. This spring quarter, philosophy professor Gabriel Lear taught a lecture titled “Aristotle on Virtue”. On the first day of class, students were fighting each other for seats. She had taught a similar course about five years ago, but back then, she only needed one TA. “Now I have to have two, and I still had to turn people away…I feel that I’m hearing more stories of students not being able to get into their first choices of classes.” In Spring 2012, 3.7 percent of all degrees in the College were awarded in philosophy, up from 2.5 percent a decade ago. Though perhaps this seems like modest increase, it takes on new significance in a year where Forbes Magazine ranks philosophy the fourth least lucrative major, with an unemployment rate of 10.8 percent for recent graduates.

Philosophy isn’t the only humanities major with more students. English Department Chair Elaine Hadley attributed the increasing popularity of the English major, up 2.6 percentage points since 2002, in part to its inherent flexibility: “This department, in relation to other departments in our discipline, does value our self-understanding as an interdisciplinary place.” But Hadley views the growth in interdisciplinarity as potentially a double-edged sword: while the slew of double- and triple-majors over the last two decades has bolstered English major numbers, the same trend implicitly questions the value of an English degree on its own.

Lear, too, noted that her department has more students double-majoring than in the past. “People, say, majoring in economics and philosophy… they feel like they’re doing something more practical—and then philosophy.”

Minors were first instituted at the University in 2003, the first wave all in humanities departments: Classics, Near Eastern Languages and Civilization, Romance Languages and Literatures, Slavic Languages, and Germanic Languages. Double- and triple-majors followed shortly after. “I heard colleagues from German saying, ‘Well, maybe not that many students want to major in German, but a number might just want to minor in German.’ So we instituted that as a way of trying to give students some transcript recognition,” said Dean of the College John Boyer (A.M. ’69, Ph.D. ’75), who initiated the changes during his third term as dean.

Minors were first instituted at the University in 2003, the first wave all in humanities departments: Classics, Near Eastern Languages and Civilization, Romance Languages and Literatures, Slavic Languages, and Germanic Languages. Double- and triple-majors followed shortly after. “I heard colleagues from German saying, ‘Well, maybe not that many students want to major in German, but a number might just want to minor in German.’ So we instituted that as a way of trying to give students some transcript recognition,” said Dean of the College John Boyer (A.M. ’69, Ph.D. ’75), who initiated the changes during his third term as dean.

Dean of the Division of the Humanities Martha Roth pointed to the downsizing of the Core in 1998 as one driving force behind this trend.

“When the College Core was reduced in its requirement somewhat, the idea behind it had been… to have students spread their wings more broadly and take approximately one third of their courses in the Core, one third in their major, and one third in two minors or exploring things they never had any ideas about,” Roth said. “Unfortunately, one of the trends has been that people are now double-majoring, so they’re doing one third of the Core, one third of their major, and one third the second major.”

“I’m not sure why they feel that’s important. I’ve counseled my own children not to do that, but people need to use this opportunity to explore and to try things you’re never going to have a chance to try again,” Roth added.

Yet in spite of her resistance to this surge, Roth also noted that flexibility and collaboration across disciplines accounted both for the historic strength of their programs and their capacity to adapt to an ever-changing market.

“Interdisciplinarity is in the DNA of this place,” Roth said, pointing specifically to the New Collegiate Division and majors like Interdisciplinary Studies in the Humanities (ISHum).

Departments have been structured with flexibility in mind. The introduction of the Philosophy and Allied Fields track and the Creative Writing Program in English demonstrate efforts to better accommodate differences in student interest.

Similarly, a burgeoning emphasis on “clusters” for undergraduates majoring in English places a premium on interdisciplinary learning. For a student interested in enslavement, for example, Hadley could encourage them to plan to “cluster” a history course on American slavery with a gender studies course focusing on prostitution.

“And what’s cool from that is just that students understand that this isn’t a grocery store—here are your Triscuits, here’s your celery…—but that you can actually construct not just a narrative but a conceptual node that speaks to some core interests,” Hadley said. “It’s kind of a synthetic thinking. Employers everywhere need people to do it.”

A smaller doctoral presence

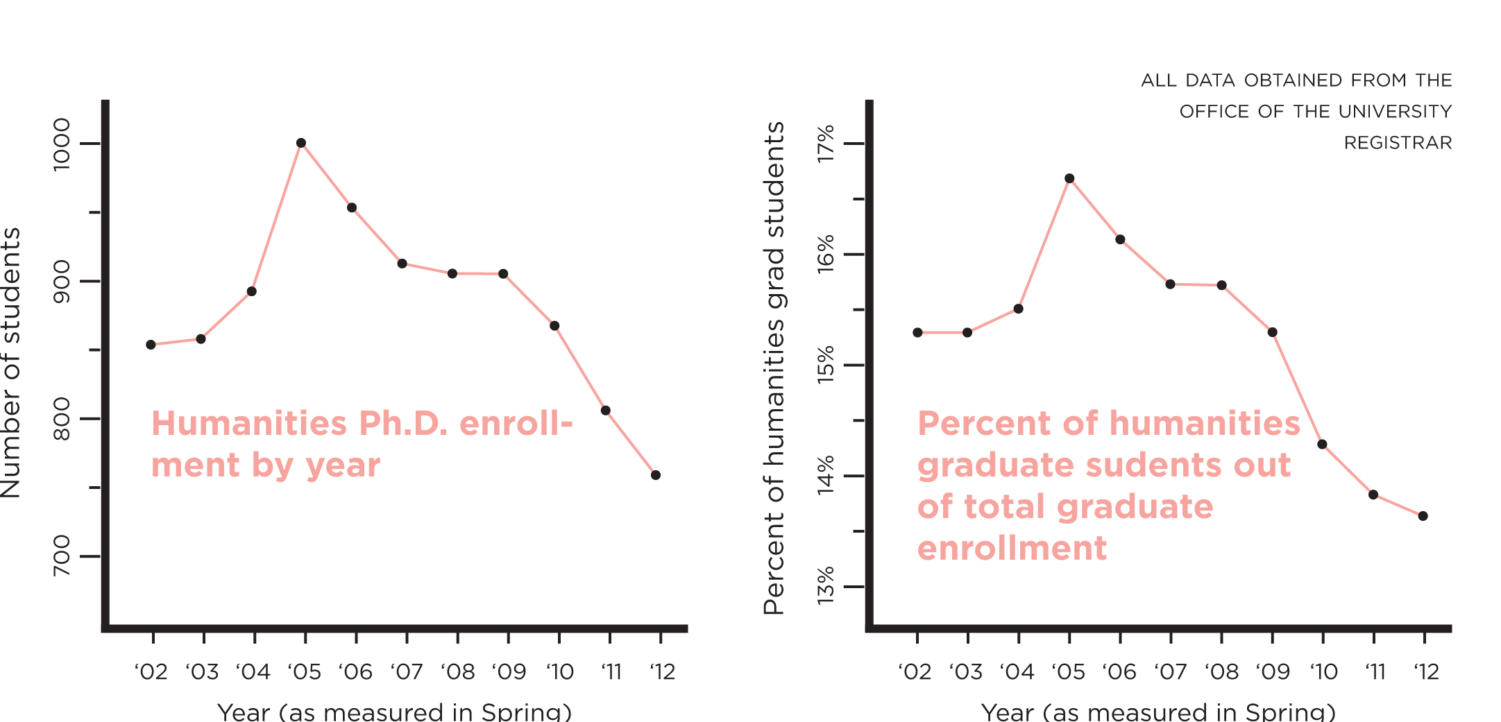

On the other hand, graduate humanities programs have faced more direct pressures from an adverse economic climate. Public universities and community colleges laid off humanities faculty in scores, and hiring has slowed to a halt—the number of available humanities faculty positions is still a third below its peak from 2007–8, according to The Chronicle of Higher Education.

“It’s really rough out there,” said Professor Malynne Sternstein (A.B. ’87, A.M. ’90, Ph.D. ’96), who became an associate professor in the Slavic Language and Literature department in 2004. “Insofar as it seems as though the economy is bouncing back overall… I think that universities in general are a little bit behind the curve,” she said.

And the competition keeps getting fiercer. “It used to be, in my day, that we weren’t expected to publish as graduate students. Today, it’s so competitive that if you don’t publish as a graduate student, you really don’t have a good chance of getting an extant position.”

And the competition keeps getting fiercer. “It used to be, in my day, that we weren’t expected to publish as graduate students. Today, it’s so competitive that if you don’t publish as a graduate student, you really don’t have a good chance of getting an extant position.”

In addition to the tight job market, the University’s Graduate Aid Initiative (GAI) has made graduate enrollment in the humanities both more affordable, but also more competitive. Announced in 2007 by President Robert Zimmer, the GAI pledged $50 million in funding to incoming doctoral students in the Humanities and Social Sciences for up to five years, covering tuition, health insurance, and a stipend. As part of the program, $2 million was allocated to providing health insurance to students who have matriculated since 2003 for the first five years in their programs.

But since each student comes with a higher price tag for the Humanities division, fewer students are being admitted. “The Humanities division in general just doesn’t have the money to fund students because the beautiful part of getting into graduate school here is that you have a full ride,” Sternstein said.

Before the GAI, graduate students were admitted with variable financial aid packages, with some paying tuition, others getting tuition waived, and many getting large stipends which were often inequitable.

“To use my own field as an example, we’d have students who would be admitted through Near Eastern Languages in the Humanities Division or History in the Social Sciences Division sitting in the same classes, with the same professors, with the same dissertations, and they’d have totally different packages,” Roth said. “And they knew it—everybody knew it. And it created a lot of morale problems.”

While many departments, such as Philosophy, had already moved toward sustainable program sizes of fully funded students, others, such as Anthropology and History, took on large classes of unfunded doctoral students. “In Spring of 2006, when Bob Zimmer was named president of the University, I was a deputy provost for graduate education,” Roth said. “He talked to me and said, ‘Fix it. We’ve got to change. This is not tenable.’”

The implementation of the GAI varied on a departmental level, depending on what the viable program size was and where they had been funding students previously. “There’s a lot of them that were already funded at the right level, so it wasn’t an across-the-board cut,” she said.

Some graduate students at the time of the GAI’s announcement felt that the package did not go far enough in providing support for current students, which culminated in a protest in 2008 during which over 150 students marched to the administration building to demand funding increases. But, many faculty members believe that the GAI has been integral in improving the overall health of their doctoral programs in the midst of a difficult economic climate.

Hadley recalled that the decision to scale back the Ph.D. program felt like it was generated in part around concerns about the humanities job market. “Part of our responsibility is not to flood that market in excess of what it can manage,” said Hadley, who has been teaching at the University since 1994. Programmatic efforts in the English department to help graduate students in the job market have included a professionalization day and a pedagogy course.

Lear noticed a similar effect of the GAI. “If you’re actually providing full funding for five years, you can’t admit as many students,” she said. But Lear also echoed the feeling of responsibility in her department. “I’m the placement officer. It’s not like there are a ton of jobs out there. We shouldn’t be admitting a ton of graduate students if we can’t have a reasonable expectation of placing them in jobs.”

For Hadley, though, the decision did not signal any kind of decline or attrition of the doctoral program. Rather, it was integral in improving the morale of the department. “I think if you walked the halls and just stopped colleagues of mine, those that pay attention to the graduate culture in the department, and you said to them, ‘Has the GAI been a good thing for the morale and spirit of the department?’ They would laugh and be like, ‘Yes’—they wouldn’t even pause to think, they would just say ‘yes,’ because they all come in, equal playing field, they know that they have their funding for a good amount of time, so there’s not this sort of panic.”

Not everyone acknowledges the connection between the job market and changes in humanities programming. “There’s never been a flush job market,” Roth said. “That’s the truth about academia. There was no ‘good old days’—they never happened. There have always been more Ph.Ds. than there have been jobs, and, in many ways, that’s what you want. If all I was supposed to do was turn out my successor for the academy, then I’d have one Ph.D. student in my whole life, and is that what I want to do? For the vitality and health of any field, you’re going to normally have more people receiving their training and degrees than there will be actual one-for-one job matches.”

To Roth, economic concern would not and does not make sense as a central consideration for UChicago when funding its programs. “It’s not. I mean, wouldn’t that be a poor world? That’s turning out shoemakers. I mean that’s not what we’re doing. We want people who are thinking…we want people who will question. I don’t want ‘yes men’ around me, I don’t want ‘Yes, Dean Roth, yes.’ No, they have to push back.”

A tricky shift

hen visiting German professor Christian Benne opened his presentation “How to Read Nietzsche” at the Literature and Philosophy workshop in March, he said he came to the University because Chicago was “the best place in the world to study the humanities.” Elaborating on his remarks, he wrote in an e-mail:

“Of course, you can find great minds and scholars at many universities, also lesser known ones, but not necessarily such a critical mass of young talent on the graduate level. This makes all the difference, and people actually seem engaged in each other’s work.”

This “critical mass” of the University—its large cohort of doctoral students—is one of the University’s most important demographics. Graduate students are largely responsible for organizing the University’s lauded workshops, of which there are currently over 60 in operation. Doctoral students are, with faculty, the standard by which Chicago’s reputation is weighed within academia.

Then, cutting back the doctoral program, Lear said, is “a tricky business, because if you cut back too far, then you don’t have a critical mass of students to form a cohort.”

Hadley felt that faculty were aware of the trend of an expanding College and decreasing Humanities graduate student enrollment. “You will hear people say, ‘You know, we used to be a graduate institution, and now we’re an undergraduate institution,” she said. “And I think that’s always an ongoing debate—and it’s a completely valid one.”

But she dismissed any hint of panic about this trend called for by older faculty. “You’re going to meet people, especially if you meet people in their 60s and 70s here, who remember a period when it was…basically a graduate institution. And that was a lovely moment, but I also remember when, you know, bread was five cents a loaf and a movie ticket for a date was $1.25. Part of it is just we’re in a different era and we have to face the realities of that.”

An ethos that endures

Ultimately, despite the apparent demographic shift, professors expressed confidence in an institutional safeguard that promises to preserve the humanities as a bastion of University culture: The Core. In 1942, Robert Maynard Hutchins, the University’s fifth president, adopted the all-Core four-year curriculum, from which the College has been gradually weaned.

What distinguishes the Core is its emphasis on primary texts, which essentially place the humanities at the center of College culture. “The kind of conversations, the kind of culture of intellectual life in the student body, I would argue, compared to other schools, is infused with the humanities, is infused with humanistic ideas,” Boyer said.

And there’s a practical connection that the Core requirement has with the University’s culture. In addition to bringing many undergraduates in contact with graduate students, who shoulder a good portion of the teaching load, “A lot of the teaching done in the Hum Core is done by the faculty, so I think this has been a way of always being able to protect the humanities…not just in terms of faculty lines and budgets but in terms of the mission of the place, which is actually quite important,” Boyer said.

From Boyer’s perspective, the University, and, more specifically, the Core, continually shapes students to fit the prevailing ethos—not the other way around.

“I’ll tell you a story,” Boyer began. “I had a debate with a couple of colleagues who are leaders of our Core courses. So, they were saying, ‘Chicago students are very special,’ because people are worried, ‘as we expand the College, are we going to recruit a different type of student?’

“So I said, ‘Let me get this straight: You’re talking about Chicago students like they’re hatched out of an egg. They end up on 59th Street on September 18th ready-made Chicago students?’ And they say, ‘Yes!’ And I say, ‘Okay, well, then what do you do with them in your Core course for the first year? What’s the value added?’”

Programs like Career Advancement, and the reduction of Core requirements, are intended to complement, rather than diminish, an education in the humanities. These programs give students the liberty to study the Humanities without sacrificing freedom of career choice. “The idea of the career programs is not to say that there’s anything wrong with the liberal arts or the humanities but rather to validate my belief that in fact these are excellent programs,” Boyer said.

Roth believed that many positions could benefit from the critical thinking skills the humanities provide. “I think there should be more people with Ph.Ds. in the humanities in the Senate and House of Representatives. I think we’d be in a lot better shape if we had people who had degrees in history or anthropology or Russian languages and literatures or philosophy. I mean, I don’t think philosophers got us into the economic mess we’re in now, so why aren’t they in government? People in all walks of life need to make decisions, weigh evidence, understand the arguments, present the arguments, and those are the kinds of skills that we teach in the humanities and we impart to our students.”

For Hadley, an ideal world would be designed perfectly for humanities Ph.Ds., but she recognizes that we don’t live in that world. “I’m a very pragmatic person, and I think we were creating an unsustainable model, which doesn’t mean that some of us don’t lobby and press for the fact that the humanistic knowledge and skill sets are incredibly valuable to society,” she said. “That’s an ongoing battle; it’s the battle we have to fight.”