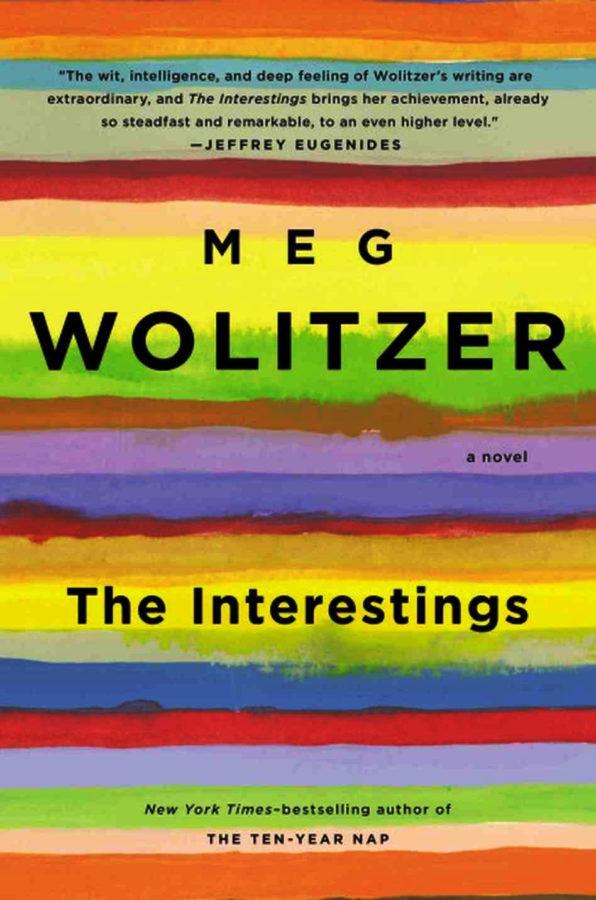

The cover of Meg Wolitzer’s latest novel, The Interestings, is painted with rainbow stripes—saturated stripes. They overlap messily, and in doing so, they gesture toward the similarly messy intersecting lives and relationships the book might contain. At the same time, the bold, thick, black font indicates that The Interestings should be taken as a novel with eminent literary potential.

On the cover there is also a quote from Wolitzer’s college friend, novelist Jeffrey Eugenides (the two were in a writing workshop at Brown together). “The wit, intelligence, and deep feeling of Wolitzer’s writing are extraordinary,” he writes, “and The Interestings brings her achievement, already so steadfast and remarkable, to an even higher level.”

In Wolitzer’s year-old essay in The New York Times Book Review about the roadblocks women writers continue to encounter in the literary sphere, she makes a comment that gives license to judge this recent book by its cover. She writes, “A writer’s own publisher can be part of a process of effective segregation and vague if unintentional put-down. Look at some of the jackets of novels by women. Laundry hanging on a line. A little girl in a field of wildflowers. A pair of shoes on a beach. An empty swing on the porch of an old yellow house.” Here Wolitzer might be digging too harshly into the dust jackets, but at other moments in the essay (which I devoured last year as admiringly as I recently did The Interestings, not realizing she had written both), Wolitzer poses a critical question: How seriously does a novel by a woman need to take itself in order to be considered as “serious” as a novel a man might write on the subject of emotions and relationships?

In the same essay, Wolitzer also addresses Eugenides directly, saying, “If The Marriage Plot, by Jeffrey Eugenides, had been written by a woman yet still had the same title and wedding ring on its cover, would it have received a great deal of serious literary attention? Or would this novel (which I loved) have been relegated to ‘Women’s Fiction,’ that close-quartered lower shelf where books emphasizing relationships and the interior lives of women are often relegated?”

I agree with Wolitzer that big-name male writers are respected automatically, and not always with good reason. When Eugenides came to the Logan Center a few weeks ago, he shared an excerpt from a new short story, and while Wolitzer may have loved The Marriage Plot, she would not have enjoyed this garish performance. Eugenides read this literary manifestation of a bizarre fantasy in exaggerated accents. It was about a Texan man who marries a Scandinavian (or is it German?) woman, Johanna, who’s looking for a faster route to a green card. I don’t remember where in Europe Johanna came from because right below her name, I wrote “FUBAR” (fucked up beyond all repair), and that’s where my notes end.

Entering Wolitzer’s story, it’s clear her sense of purpose isn’t limited to the covers around it. “The Interestings” is the name of 15-year-old Jules Jacobson’s new friend group the first time they all gather at Spirit-in-the-Woods, an arts summer camp, in the ’70s. There, Jules falls in love with people who will be the major figures populating her life over the subsequent decades, including Jonah Bay, who’s the son of ’60s folk royalty; wealthy, delicate Ash Wolf; her charismatic older brother, Goodman; and ugly Ethan Figman, who’s crazy about Jules that summer and for the rest of their lives. Ten years later, Ethan and Ash are married and artistically successful, Ethan as the creator of an animated TV show, Ash as a theater director. Jules and Jonah have both abandoned their artistic ambitions, though for different reasons. Goodman, meanwhile, has fled the country after being accused of rape by another Spirit-in-the-Woods attendee. Though Jules’s and Ethan’s relationship is the emotional centerpiece, all the main players get relatively equal amounts of airtime throughout this epic of relationships, so that the pattern of narration and action, and the parade of characters, varies often.

There are many life truths in this book with practical application for readers of all ages, for Wolitzer follows her characters diligently all the way through adolescence and young adulthood into their 30s and, more tentatively, into middle age, where she herself is now. (Maintain a balance between personal and professional life, always; experiment in your 20s; marry someone you like to hang out with.) The novel picks up pace as it moves through the collective life of the group, just like real memory tends to do. When the adolescent Jules rules the narrative, descriptions of individual incidents are longer and lusher, but as she moves forward, there’s more zooming. Nixon’s resignation gets three paragraphs, while the 2008 recession is one clause in a single sentence. The zooming continues, until events both political and personal come in waves so huge you fear the group will topple by the end of the book. It’s questionable the group even matters at the close, when it turns out that “The Interestings” are not the people, the artsy teenagers, with whom Jules Jacobson was originally infatuated, but what passes between them and around them—the lives they ultimately claim.

This novel has more human qualities than any other I’ve read lately. For example, it’s kind of hard to look at sometimes, when its syntax or dialogue grows awkward, or when its pages don’t look exactly right from far away (interestingly enough, Eugenides mentioned at Logan that each page of one of his novels needs to have the right appearance before he considers the book finished). It’s also funny and sad from moment to moment. The Interestings has sold incredibly well so far, having garnered admiring reviews. And yet Wolitzer may still think that, as a woman, she has a literary obligation to present her work with a certain affect or flair. She should know that this book will not be placed on the “close-quartered lower shelf,” and that there’s not just one way to read her latest work, which should be approached with as much of a sense of humor—and sense of grave purpose—as life itself.