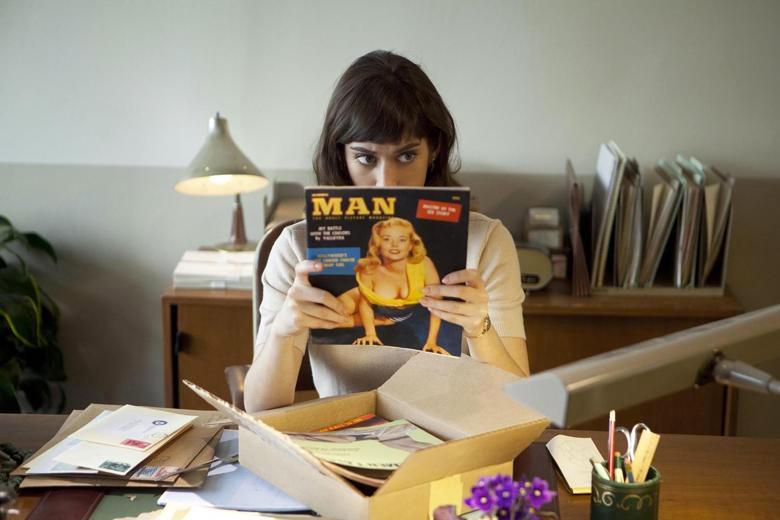

Showtime’s newest series, Masters of Sex, premiered last Sunday, September 29, amid a firestorm of bus stop ads and TV trailers. The series dramatizes the real life exploits of Dr. William Masters, a brilliant ob-gyn at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, and Virginia Johnson, an ex–club singer turned professional assistant, as the two dive head first into the complicated world of sex in the 1950s. Along the way they try to answer questions: “What happens to the body during sex?”, “What happens to the body during orgasm?”, and “Why would a woman fake an orgasm?” The series, based on a biography of the same name by Thomas Maier, stars Michael Sheen as Masters alongside Lizzy Caplan as Virginia “Ginny” Johnson.

From the opening shots of the pilot, the series sets up the strange worlds through, above, and under which Masters conducts his studies and leads his personal life. The episode opens with Masters attending a candlelit banquet more appropriate for a meeting of aging philosophers and academics than for honoring a brilliant scientist. Sheen manages, however, to render Masters insouciant, and even slightly boyish, in a GQ-worthy tuxedo and black bowtie. We follow Masters quickly from there to a closet, where he spends late nights timing the orgasms of a prostitute and her desperate customers.

Sheen plays Dr. Masters with a spot-on mixture of deadpan and affability. His monologues, which often tend toward the dramatic, are delivered with a surprising humanity and impeccable timing that wins you over as he whiles away his hour on the screen. Sheen and Caplan pull the roles off with aplomb, bringing the lofty lines down a notch with their foibles. Virginia Johnson is constantly caught between a smile and a grimace, and the enigmatic Masters only seems the tortured-but-brilliant scientist until his face suddenly brightens and he starts hankering for a martini. Nicholas D’Agosto, as Masters’ sexually charged resident Dr. Ethan Haas, is the only real weak link in the shows’ performances.

What strikes me most about this intriguing new series is how it manages not to fall neatly into any of the boxes it seems relegated to on paper. Each character has aspects of sitcom tropes: oversexed supporting male; headstrong and beautiful female; brilliant but overworked lead. But each character then turns out to be not entirely what we bargained for. Oversexed quickly becomes romantic; headstrong starts to feel cold and lonely; and brilliance stops being dazzling. Masters and Johnson feel believable because they are both trying to fit into roles society has provided them instead of being the living incarnations of those roles. Neither can be entirely devoted to their work or their personal lives, and they aren’t always able to shed their lab coats before climbing into bed or leave their emotions at the front door. Which is good news for the show.

Apart from the drama, however, the show also has moments of fun and humor. Masters’ interactions with his previous, stuffy secretary, or Haas’ unbridled enthusiasm about sex provide relief from lofty speeches and arguments. Which brings us, once again, to the unavoidable topic of sex.

It would be simply impossible to discuss this show without talking directly about sex. A summary of sex in Masters, however, is not easy to pin down—one of the show’s greatest strengths is in how much scenes vary in setting and tone while characters strip down and, in the words of Beau Bridges as the hospital provost, “flop around on beds.” Sex in this show, if you can even place it all under that category, doesn’t always involve two young and languorous heartthrobs tangling themselves in knots to cover their genitals in silk sheets. It happens in shirtsleeves and socks, or hooked up to an EKG machine, or in a dingy rented room with a prostitute in garters. It also includes little of the Game Of Thrones’ so-called “sexposition.” Intercourse is a time for few words, with those few voiced somewhere between a whisper and a groan. And, even more importantly, sex means something different to almost every character. It alternates between physical and emotional, business and pleasure, empty and fulfilling. But mainly, it hovers somewhere in between all these definitions. Even if our culture has changed enough to allow sex on TV, perhaps we haven’t really changed that much in the way we have it.