While the Logan Center stands as an icon for everything forward-looking in the arts, its performance hall was also used Saturday night in a presentation of an antiquated but remarkably vibrant art form: silent film with live musical accompaniment.

From silent film’s very beginning, said film professor Tom Gunning in the Q&A session that followed the performance, “The cliché is that it was never silent. It was accompanied by music and also, often, by sound effects.” Gunning quoted the German philosopher Theodor Adorno: “Music came into silent film playing very much the same role as children whistling when they go past a graveyard on Halloween. In other words, it dispelled the almost ghostly nature of the films, which were black and white and silent.” But that audio was rarely recorded and thus ephemeral.

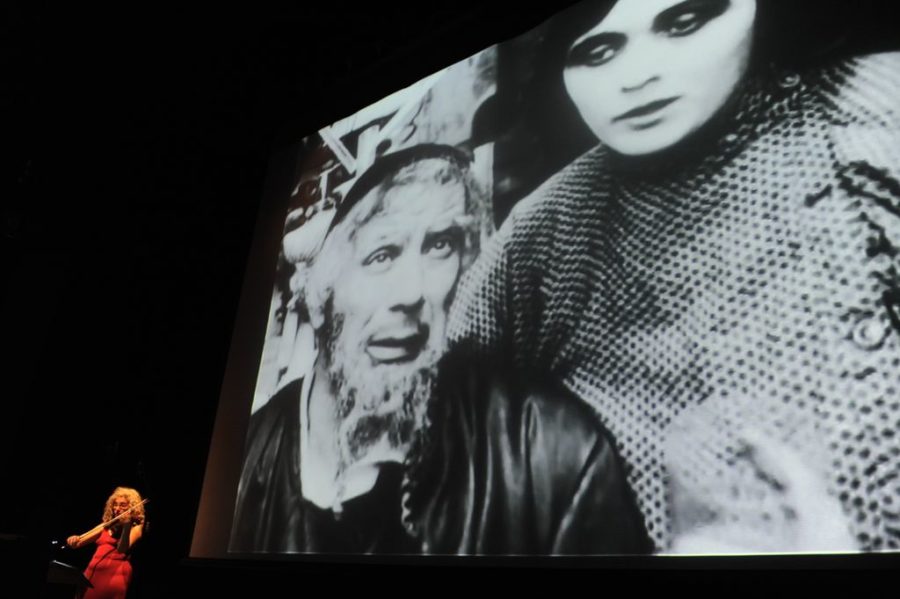

The Yellow Ticket (Der Gelbe Schein) of 1918 is an early work of the great silent film actress Pola Negri (born Apolonia Chałupiec), the first European actress to become a Hollywood star. Born in a small Polish town in 1894, she made it to the theater stages of Warsaw and then starred in several German films before she went to Hollywood, where she had love affairs with Charlie Chaplin and Rudolf Valentino.

The film was produced by German directors Vicor Janson and Eugen Illés and was filmed in Nalewki, the Jewish quarter of pre-WWII Warsaw, which was completely flattened during the war and of which little footage remains. The film’s opening shot of a turn-of-the-century home is in itself a testament to lost Jewish history. Produced for German and Jewish audiences alike, the film is a commentary on the anti-Semitism of tsarist Russia, then Germany’s enemy in World War I, as compared to Germany, where Jews were then fully emancipated. During a reversal of German policy toward Jews under the Nazis, most copies of the film were destroyed, and it was largely forgotten until a copy was found in Berlin and digitally restored in 2012.

Negri plays Lea Rabb, a Jewish woman who yearns to become a doctor to heal her ailing father. When he passes away, she travels to Saint Petersburg to begin her studies at the university. In order to enter Petersburg as a Jewish woman, however, Lea is forced to register for a “yellow ticket,” the blanket designation for all undesirables, notably prostitutes. Taken in by a brothel owner, Lea is pressured to entertain men to pay her rent, but remains true to her character and is repulsed by them. Jews were also not admitted to the university, so Lea must use a birth certificate she discovers to register for classes under a non-Jewish name. Despite her challenges, she retains a passion for her studies, earning an award at the university.

Bucking the pantomimed overacting one expects from silent films, Negri is powerful but subtle throughout in conveying the uneasiness of Lea’s dual identity. With her heavy black eye makeup and mysterious features, one can see why she was often cast as exotic characters in her Hollywood films, such as a gypsy in a film adaptation of Carmen.

When a man at the brothel recognizes Lea from the university, he exposes her true identity to her would-be Russian lover Dimitri, who abandons her. Fearing that her future as a student is doomed, Lea breaks down and leaps from a window in a suicide attempt. In that climactic scene, an extremely long take by today’s standards, Lea’s expression slowly and subtly changes from desperation to madness, her gestures shifting from those of helpless collapse to demonic possession.

It is around then that Lea’s professor discovers that she is actually his daughter from a woman he met while he was a student years earlier, and he heals her injuries. The film can be read as having a Hollywood happy ending, with Lea reunited with her true father and Dimitri due to the happy realization that she is not Jewish. But this is not so clear: Why did the professor not marry Lea’s mother, and why did she drop Lea off at a doorstep in the Jewish ghetto? We are left wondering whether Lea could be a Jew after all.

The performance featured live accompaniment from Grammy-winner Alicia Svigals, one of the world’s foremost klezmer fiddlers and a founder of Klezmatics, with Marilyn Lerner on piano. Svigals wrote an original score for the film that draws from klezmer, music of Eastern Europe’s pre-war Jewry, and evokes instruments such as the shofar, a horn used in Jewish religious practices. In one scene, she makes a beat box–like panting sound to evoke the ghosts of the destroyed Jewish community, as she said after the film. At one crushing moment in the film, she produces wailing evocative of Eastern European folk music.

Svigals’s nuanced violin variations and soaring melodies are matched in intensity by Lerner’s dynamic chords. Together, the two follow the film’s cuts through optimistic moments and scenes of despair.

While this was Svigals’s first experience composing and performing for silent film, she was in a way returning to a long lost tradition. “My grandfather made a living for a time playing piano for silent films a block away from where I live now,” she said.

Svigals and Lerner are touring North America on a grant from the Foundation for Jewish Culture. This screening was sponsored by the Logan Center for the Arts, the Center for Jewish Studies, the Film Studies Center, and film professor Tom Gunning.