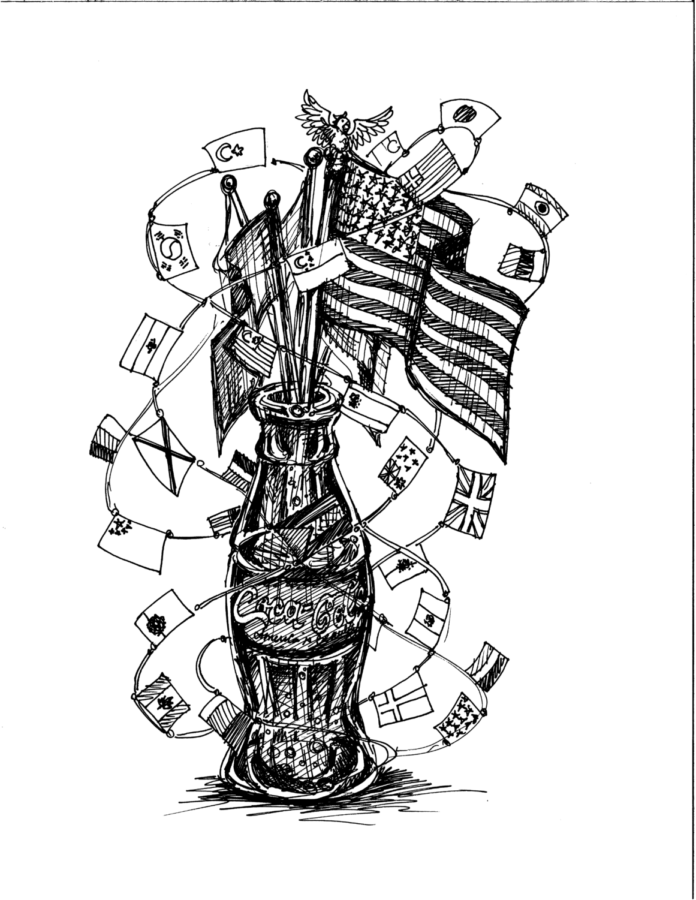

Coca-Cola, which has long been associated with imagery like cute polar bears and Santa Claus, has not exactly developed a reputation for provocative advertisements. And one of the commercials that debuted last Sunday during the Super Bowl seemed to fit right in with the other “aww”-inducing advertisements that Coke often rolls out; “It’s Beautiful” featured children singing “America the Beautiful” in different languages while scenic clips played of happy people enjoying Coke around America.

Nevertheless, proving that people can get angry at just about anything, numerous tweets responded negatively to the inclusion of foreign languages in the commercial. The reaction to the Coca-Cola commercial hasn’t been uniformly condemnatory. But as someone who comes from a bilingual household, I can’t say I’m astonished by the social media backlash, which sounds simply like a highly public version of the negativity that I’ve heard expressed toward foreign languages throughout my life. Though people in college settings like ours seem to see multilingualism as a sign of being smart and sophisticated, back when I was a kid, speaking Mandarin within earshot of another kid who wasn’t Chinese invited open mockery.

The day after the Super Bowl, former congressman Allen West published a blog post on his website describing the commercial as “Coca-Cola’s politically correct attempt at the balkanization of America.” The charge is absurd. If anything, Coca-Cola’s ad demonstrated the merits of inclusivity. Despite being unfamiliar with Hindi, Tagalog, or most of the other languages featured in the commercial, I understood what everybody was singing because “America the Beautiful” is an iconic song. I don’t need it to be sung in English, because I already know all the words. However, Coke was able to make a piece of American culture accessible to a broader cross-section of people, integrating different heritages into that piece of culture.

And indeed, the English language itself has a long history of integrating contributions from other languages. For those who are dismayed by the influence of foreign languages in the United States, I suggest that they try to go about their daily lives without using any words that have been borrowed from other languages. Good luck ordering one of those hot brown drinks from Starbucks, or describing that year of school between preschool and first grade. Not only does the exchange of words help build bridges between speakers of different languages, but it also helps English speakers communicate with one another. How many instances in our lives have we spent time searching for just the right way to say something? Whether we’re tapping away at essays on our computer, talking to our friends, or playing a heated Scrabble match, adapting words from other languages adds to our toolbox of the perfect words we need. In this way, English becomes stronger, not weaker.

One of the common arguments against promoting foreign languages in America is that unity will be undermined if people can’t communicate with one another. In a broad sense, I agree that we have a communication problem in the U.S., given the divided reactions to Coca-Cola’s celebration of multilingualism. However, communication is not predicated solely on people speaking the same language; understanding one another’s experiences is also critical.

When we get into policy debates about the place of foreign languages in schools, public life, or cultural events, we ought to be aware of what some of the concrete impacts might be on individuals. Consequently, I believe that every American student should be encouraged to learn a foreign language. Aside from the mental exercise and résumé boost that are often cited as reasons to learn foreign languages, spending some quality time conjugating verbs or trying to memorize the genders of all the nouns gives people some insight into the challenges encountered by those who came to America and adapted to not only speaking a new language, but also living in a new culture which shapes and has been shaped by its language. Given that the United States is a nation of immigrants, many of whom arrived from non-English-speaking countries, foreign languages ought to be considered as much a part of the American experience as the proverbial baseball and apple pie.

Perhaps equally important, learning a foreign language could teach people to be less fearful of the unknown. Just as some of our parents urged us to look under our beds to assure ourselves that there were no monsters there, we need to ask people to look at foreign languages to realize that they don’t contain any magical incantations that can be deployed to ruin the America they know. In these other languages, people can still ruminate on life, debate the merits of Coke versus Pepsi, or even sing “America the Beautiful.” Instead of allowing fear to persist, we should seek to use foreign languages to teach empathy and mutual respect for one another’s heritages. And that would be a rather beautiful thing to experience, wouldn’t it?

Jane Huang is a fourth-year in the College majoring in chemistry.