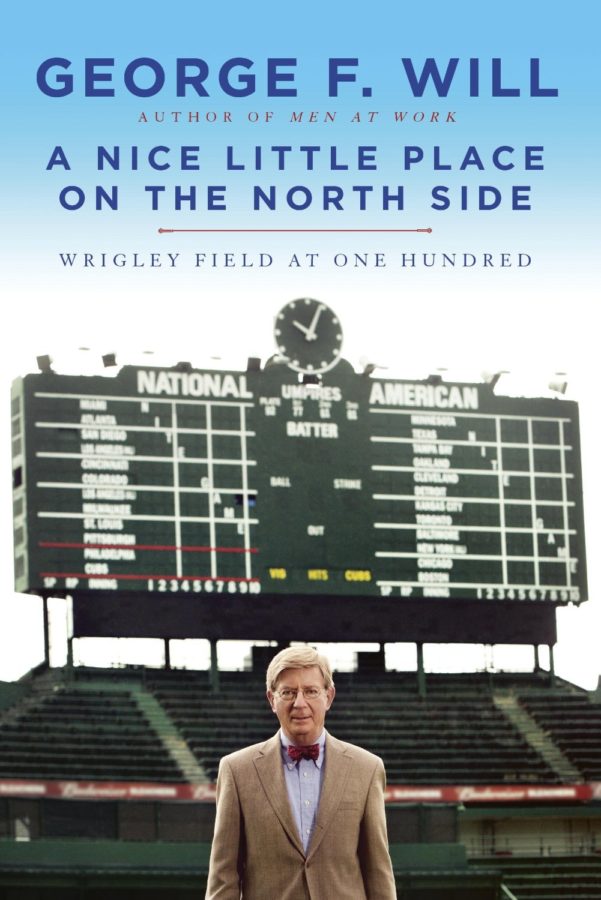

A formerly proud sports tradition, with which success was once synonymous, worn down by decades of failure until it was stripped of all its former dignity and relevance… no, I am not talking about our sports program here at the University of Chicago, but the professional baseball outfit which calls the North Side its home: the old Chicago Cubs. Chicago’s more listless (I don’t want to take away from some of the White Sox’s own futility) baseball team is the subject of a new book by longtime political commentator and occasional baseball enthusiast George Will, entitled A Nice Little Place on the North Side.

That nice little place, Wrigley Field, has a somewhat legendary reputation in baseball. Built in 1914, it is the second-oldest remaining baseball park in the nation after Boston’s Fenway Park. Yet despite its immense age, even Wrigley is not old enough to remember the Cubs’ glory days in the first few years of the 20th century. Back then the Cubs were dominant enough to win two straight World Series titles in three straight appearances, but it’s doubtful that there’s a man alive who could tell you how the Cracker Jacks tasted at those few glorious games so long ago.

Will himself was born more than 30 years after this run of successes, and he’s already several years past 70. Still, he starts his chronicle not with the 1940s, the decade of special futility into which he was born, but instead traces the history of the Cubs back to the mid-1800s when professional baseball was first beginning. He hits all of the major eras and events from Cubs history: the glory days, the decline in the early 20th century, the entrance of owner William Wrigley, Jr. and the stadium built in his name, the era of the legendary Ernie Banks in the 1950s, the brief but heartbreaking near-miss of the great 2003 Cubs team and all the way into today. And as any good historian should, Will intersperses this kind of bare bones accounting of events with little-known facts and anecdotes, such as the case of one player who received a constant shipment of champagne for his dying father from none other than Cubs superfan Al Capone.

The book’s early sections lack a bit of personal insight and feeling to give life to these events—which makes sense, as the author was not alive to experience any of them. The times in Cubs history which Will can personally recall are where his book becomes far less dry and more involved. His analysis of the importance of baseball in 20th-century American society and culture, which was also largely the subject of two other books by him (Men at Work and Bunts), is where the real value in this book lies. The unconditional devotion coupled with crushing pessimism which he and the Cubs fans of Chicago at large hold for their near-hopeless baseball team is one of the more fascinating examples of fan dedication in all of sports. Yet perhaps that devotion is overstated, as the Cubs attendance rates have done nothing but steadily decline in the decade since that last great 2003 team.

There’s surprisingly little writing on the actual playing of baseball itself here, which might say more about the sport than about Will’s writing ability. However, this lack of on-the-ground narration does cause the book to pale in comparison with some of the great sports nonfiction of the recent past, such as last year’s Monsters, a very similar book about the Chicago Bears by Rich Cohen. In that book, the actual playing of football was inextricable from the social and historical contexts on which Cohen was writing. The same cannot be said about Will’s effort.

Still, George Will is very passionate and extraordinarily knowledgeable about the topic he is covering, which always makes for good reading regardless of the lack of inherent excitement in the prose. Sports nonfiction enthusiasts beware, but for any Cubs fan, or for anyone interested in Chicago sports history, A Nice Little Place on the North Side is certainly no bunt.