In the titular poem of her Pulitzer-winning collection, The Wild Iris, Louise Glück takes on the voice of a flower and proclaims: “You who do not remember/passage from the other world/I tell you I could speak again: whatever/returns from oblivion returns/ to find a voice.” As a poet, Glück of all people would know about voices—her ability to inhabit the personas of everything and everyone from flowers to characters such as Persephone, Penelope, and Dido are part of her claim to poetic fame. But speaking at the Logan Center last Thursday, May 8, Glück said her newest book is centered on a new type of expression: silence.

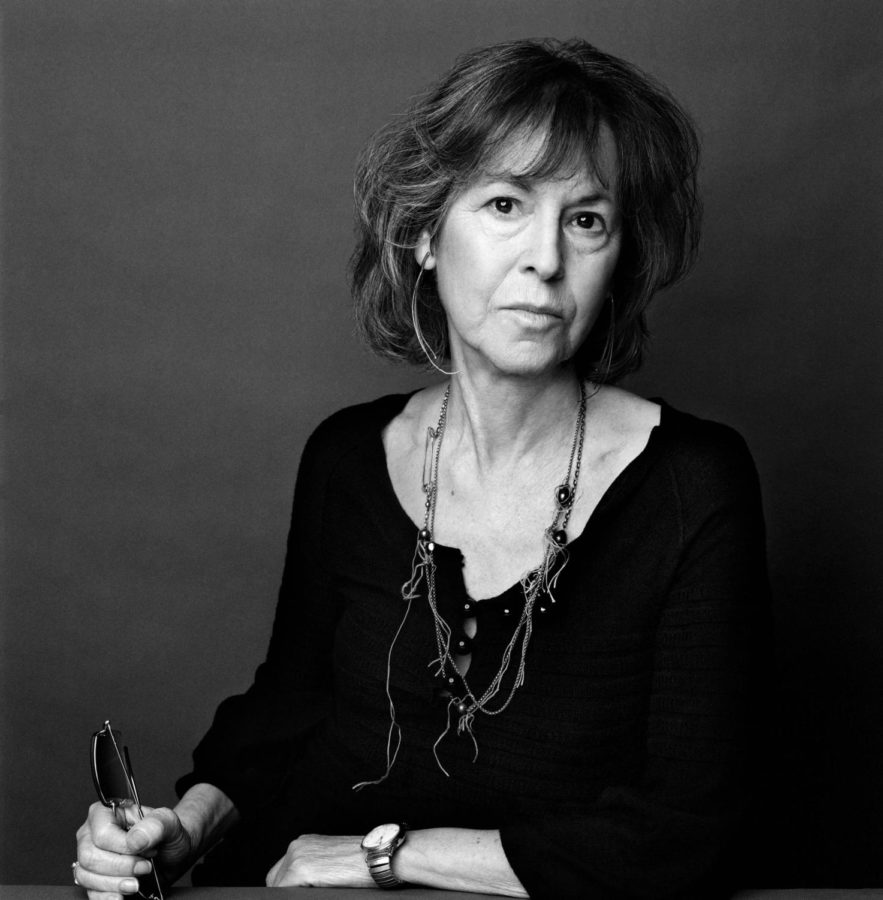

Grey-haired, slight, with sharp black eyes and wearing a dramatic cut-out black shirt, Glück looked like the kind of sharp-witted, shrewd professor who doesn’t let any BS pass in class. If you’re at all in step with the poetry world, Glück is a giant, her poetic presence almost akin to the mythological figures that populate her work—which has been described over and over again as fierce, focused, and intense. She’s the recipient of innumerable poetry prizes, has served as U.S. Poet Laureate, has taught poetry at Williams College and is now at Yale. Her clinically detached, razor-honed poetic style is difficult to match anywhere.

The accessibility of Glück’s poems belies their subtle, profound insights, their humor, and the feats of creative genius which have her speaking from the voices of so many various objects and characters—and yet also in her own, surprisingly empathetic voice. It is perhaps this creative empathy, which may, despite or because of its unyielding quality, enable the depth of imagination required for her book-length sequences of poems and give them their widespread popularity.

She read from Faithful and Virtuous Night, her new collection which will be published this September by Farrar, Straus & Giroux. The book centers around an artist who can no longer paint. Following on the heels of Glück’s first large volume of collected poetry last November (the publication of which she at first resisted, thinking it would be too “valedictory”), this collection will take on the questions of old age and artistic work about which Glück, 71, says she now feels allowed to write.

Glück acknowledged that her usage of parables and allegories within the book helped to create its narrative, and it is the mixture of these poems with those from the painter’s voice that she hopes will give the book a “billowy” quality. Yet Glück, in the (paradoxically) straightforward-yet-oblique manner that creates such intensity in her poetry, did not read from the artist’s point of view. Her reading style, clear, focused, and dry, did not prepare me for the kindly humor with which she met the audience’s questions: She spoke frankly on her love of teaching, her tarot-reading sessions, her hatred of poetry readings, and her pleasure in traveling.

Her selections included “Parable,” from the point of view of a group of wanderers—or are they pilgrims? —questioning the purpose of their journey; “A Sharply Worded Silence”; and “Aboriginal Landscape,” which memorably opens with “‘You’re stepping on your father,’ my mother said.” Her poetry, frequently taking the form of a casual narrative, occasionally shocks with such hidden gems as, “I was like you once, he said, in love with turbulence.”

Despite Glück’s fears, the collections of her works are far from being valedictory. Instead they are opening up her work to larger audiences. Her own distinctive voice shines through even in her poems on silence. And her reception among poetry-lovers proves that whatever the future holds in store for Glück, it will be anything but silent.