There’s a certain majesty, a sense of royalty if you will, to Terrence Howard’s performance in Fox’s new drama Empire. Playing Lucious Lyon, a gangster-turned-gangster-rapper-turned-record-label-owner, there are a great many stereotypes and acting tropes from which Howard could draw. He turns to almost none of them, drawing instead from the likes of Shakespeare and the regal characters he portrays. Every move he makes, every word he speaks, is deliberate and controlled. He turns smoothly, walks softly, but enunciates each syllable with an iron core. He sits in chairs like they are thrones, gazing unblinkingly and projecting power without moving an inch. It is hard not to look at him and see a king.

And his queen, or more accurately, ex-wife (Taraji P. Henson), might be even better. She is just as controlled, but moves with pace and purpose. Her words have an edge of steel to them, and her co-stars seem to feel it whenever she opens her mouth. Her character, Cookie, has just been released from prison after spending a quarter century taking the rap for Lyon’s old drug-dealing ring, and she wants compensation for the million-dollar business whose existence is owed to her. These two leads have gravity in their performances: The rest of the cast revolves around them, and scenes are warped and bent by their presence. When they are on screen together, you can count on some serious fireworks.

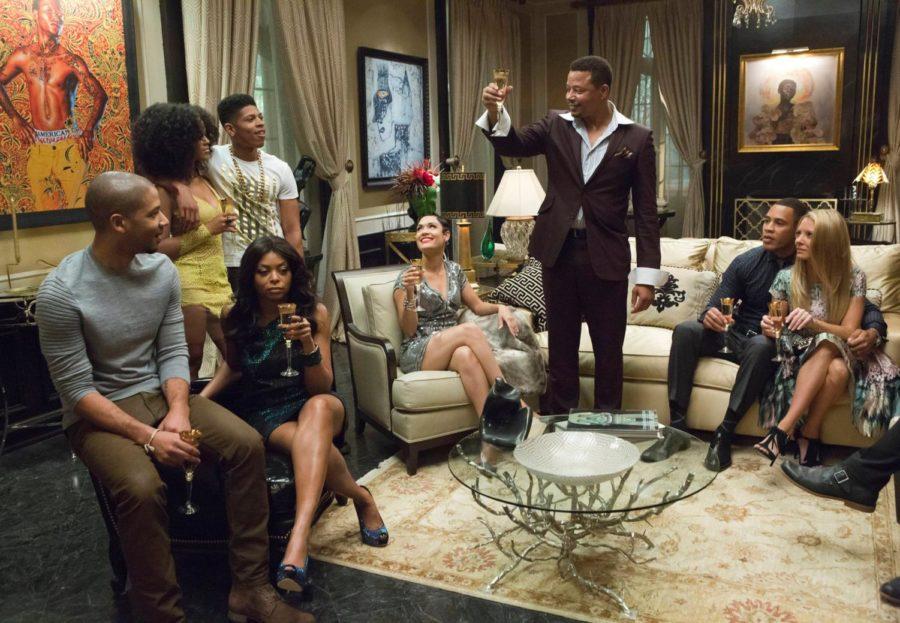

Unfortunately, the rest of the show cannot live up to the standards set by its excellent leads. The story picks up when Lyon is diagnosed with a case of ALS that will kill him in three years, ice buckets be damned. His label is about to go public and he has to choose one of his three sons to inherit leadership of the label after his death: one a talented rapper lacking in intelligence and work ethic, one kind-hearted but disliked by his father for his homosexuality, and one who is adept at the business side of the label but has no artistic inclinations. The three sons at once compete with each other and get caught in the web of intrigue between their estranged parents.

Empire is a succession drama in the classical sense; it is not a coincidence that Howard and Henson perform more like monarchs than music moguls. One of the characters unsubtly name-drops King Lear in the first episode, and the setting is very similar to Shakespeare’s classic tragedy. However, it may prove difficult to execute a tale so reliant on deceit and plotting when the dialogue is so bald-faced. There are never any embarrassing lines in the vein of Fox’s other new drama Gotham, but the script almost completely lacks subtext; every character says exactly what they mean in every scene. Conflicts are quick to come out in the open and often even quicker to be resolved.

It doesn’t help that the cast, apart from Howard and Henson, leaves much to be desired. Show creator Lee Daniels (The Butler, Precious) has a track record for coaxing the crazy out of his performers but seems to be playing it safe in Empire. Maybe it’s because they don’t get enough screen time to grow comfortable in their roles, but more often than not the supporting cast feels like walls for Howard and Henson to bounce their stuff off of. They are very much part of the scenery that the two leads spend the show chewing up.

Empire feels like the television equivalent of a film like The Theory of Everything or a weaker version of a Bennett Miller film: a performance piece that lacks structural integrity in other areas of story-telling. Without Howard and Henson, it is doubtful that Empire could stand up on its own merits, and it remains to be seen whether it is even possible for performances alone to carry a TV show in the long run. Nevertheless, those two make the show fun to watch and the scenario has the potential for some excellent soapy melodrama.