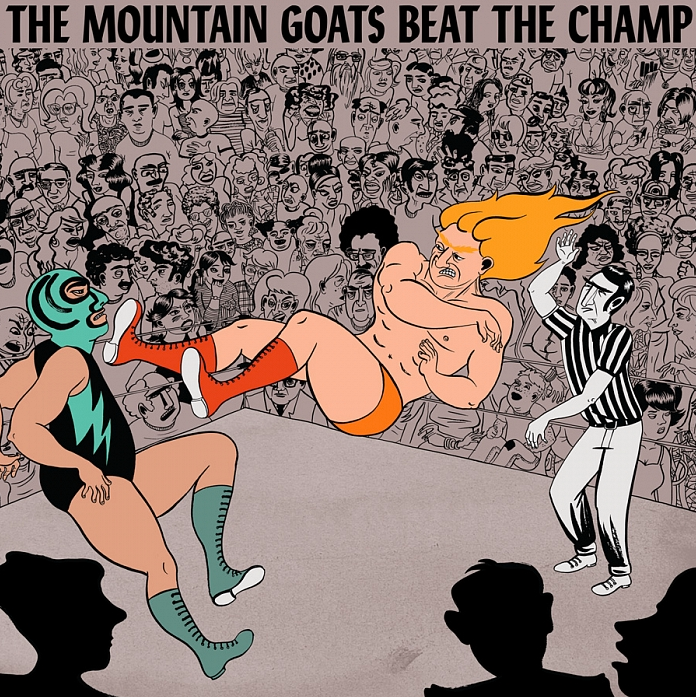

Yeah, so, The Mountain Goats made an album about pro-wrestling. It’s called Beat the Champ. Pro-wrestling is pretty outré for an indie-rock band, but band frontman/acclaimed novelist John Darnielle has also made an album where each song was inspired by a Bible verse, so it’s not like he’s ever bowed down to the interests of the musical literati. Come to think of it, the Bible’s probably even less popular than pro-wrestling among that set, although there’s likely a lot of crossover between the fanbases of the Bible and the WWE. Perhaps Darnielle’s only embarking on a misguided brand outreach campaign?

Anyway, yes, pro-wrestling. It’s wacky, right? But if you’ve heard only a single Mountain Goats song, you’d still know that wringing sublime tragedy out of the most profane subjects is kind of Darnielle’s thing, whether that subject is death metal (of which the songwriter is a real-life fan), The Price is Right, or the city of Chino, California. Lately, Darnielle has focused a few songs per album on a particular celebrity, exploring the little struggles in the lives of Liza Minnelli or Amy Winehouse that add up to a picture of the struggle to wake up in the morning and maintain what one has left.

Looking at his music in this way, pro-wrestling, and specifically the pre-WWE era of regional promotions in the late 70s, is actually the ideal subject for one of these explorations. The “nameless bodies in unremembered rooms” Darnielle growls about on “Werewolf Gimmick” take the stage, and Darnielle goes to work finding the little moments that capture the agony and ecstasy of wearing a costume and pretending to beat up other people for money and… immortality?

Maybe—Apache Bull Ramos (on whom Darnielle bases “The Ballad of Bull Ramos) winds up blind and missing a kidney because of diabetes, left with nothing to do but sit on his porch and try to remember his former glory. But even his surgeon is able to recognize him, and somehow he knows he’ll live forever, standing in the desert with his bull whip ready to “rise surrounded by friends.” On the other hand, Bruiser Brody suffers some fatal misfortune in “Stabbed to Death Outside San Juan,” and finds himself “climbing down the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram,” unnoticed by the crowds in the arena.

Putting aside the metaphysical side of wrestling, Darnielle emphasizes that beating the shit out of some motherfuckers can actually be a lot of fun. In the short, bouncy, “Foreign Object,” a wrestler hams up for the microphone and gives as good as he gets, promising to “personally stab you in the eye with a foreign object.” His personal ethos? “If you can’t beat ‘em make ‘em bleed like pigs.”

The swaggering woodwind section of “Foreign Object” is a good example of how the Mountain Goats continue to expand their sonic profile, long the most overlooked aspect of any Darnielle-led band. A solid sax anchors “Foreign Object” in the same way a more reflective woodwind ensemble gives “Southwestern Territory” a wistful melancholy that sticks around for the rest of the album. “I try to remember what life was like long ago,” sings the unnamed, hapless narrator. “But it’s gone, you know.” “Luna” and “Fire Editorial” have a jazzy, off-Broadway feel that would have been almost unthinkable to those who only know the Mountain Goats from their early acoustic-guitar-on-a-boombox releases.

Wrestling is, of course, a spectator sport, and Darnielle lends his perspective on seeking salvation through his favorites’ victories to some of the albums most affecting moments. “The Legend of Chavo Guerrero” and “Hair Match” present highs and lows in the career of the titular wrestler, and likewise in the mind of his biggest fan, 11-year-old John Darnielle, who’s watching a Spanish-language broadcast because Chavo’s the only person he knows who actually fights for good.

But heroes can let you down. In “Heel Turn 2,” the album’s complicated moral center, deciding to break bad, to go from being a “face” to a “heel,” goes beyond symbolism; it’s about survival. Sometimes the mantra of “I don’t want to die in here” needs to overrule your convictions, your instinct for fairness, and your crying fans. It’s wonderful for the marginalized, for the person who knows they’ve been beaten. When Darnielle sings “You’ve found my breaking point. Congratulations.” His voice hitches just a little on the last word, capturing oceans of resentment, bitterness, and resignation in half a second. It’s the brilliant, earnest stuff fans have come to expect from the Mountain Goats. Every form of sports entertainment should be so lucky as to have a tribute as great as Beat the Champ.