In 1507, under the reign of King Henry VII, the body of a murdered infant was found floating down the Thames River. At the same time, the king’s chief ministers imprisoned an innocent merchant in the Tower of London while an unassuming local townswoman lied under oath. Someone owed the king £500, but who? And for what? Half a millennium later, a curious historian discovered a tattered and rat-eaten scroll within a scroll in the depths of the Westminster Abbey archives, resurfacing an age-old mystery.

At Sunday’s lecture, “A Murder in Tudor England: A Warning for the 21st Century,” UChicago alum and Royal Historical Society Fellow Mark Horowitz (Ph.D. ’08) turned his academic research into an interactive sleuthing game not unlike Guess Who, entertaining, seducing, testing, and befuddling the audience along the way.

As the attendees—a crowd of alumni interspersed with a few brave students—nibbled on their bangers and mash, biscuits, and tea, Horowitz brought his participants up to speed on the history of England’s Wars of the Roses. A summary: After more than 20 years of fighting between the houses of Lancaster and York, Henry VII took control of England and founded a new dynasty aimed toward stability, security, and solvency. To accomplish this objective, the new sovereign introduced a system of bonds—written contracts that citizens used to swear allegiance to the king. If broken, these bonds would cost the citizen a hefty monetary sum, yet, regardless of the risk, citizens of all classes possessed these bonds.

Thomas Sunnyff, a haberdasher (merchant who sold small sewing articles) in Ludgate, England, was a well-to-do possessor of one of these bonds. When Horowitz discovered a document titled “The Complaint of Thomas Sunnyff Against Camby” in Westminster Abbey, he read about Sunnyff’s life and struggles. He learned that Sunnyff had a wife, Agnes, and several children. The family hosted a young woman, Alice Damston, who worked for them. All was well until two of King Henry’s chief ministers, Sir Richard Empson and Edmund Dudley, began to harass Sunnyff and Agnes, claiming that, according to the testimony of Damston, Agnes had murdered the child found in the river, with Sunnyff as an accomplice.

Sunnyff was taken to the Tower of London, where he recorded his grievances. Even after Damston confessed that her claim was false and Agnes was acquitted, Empson and Dudley continued to hold Sunnyff captive, demanding that he pay £500 for bail (for reference, at the time it took a farmer an entire year to earn £1). Eventually, a perplexed and frustrated Sunnyff went along with what he was told, paid bail, and returned home.

His discovery of this bewildering document launched Horowitz on a long campaign of research into the key figures in Sunnyff’s story—a campaign that lasted 30 years. In reviewing Dudley’s official record book, Horowitz noticed that Dudley had recorded a £500 bond default payment for the “murther of child.” In an upper corner of the page, Henry VII had scribbled his initials, condoning the transfer of payment. However, Horowitz could not yet link this payment to Sunnyff.

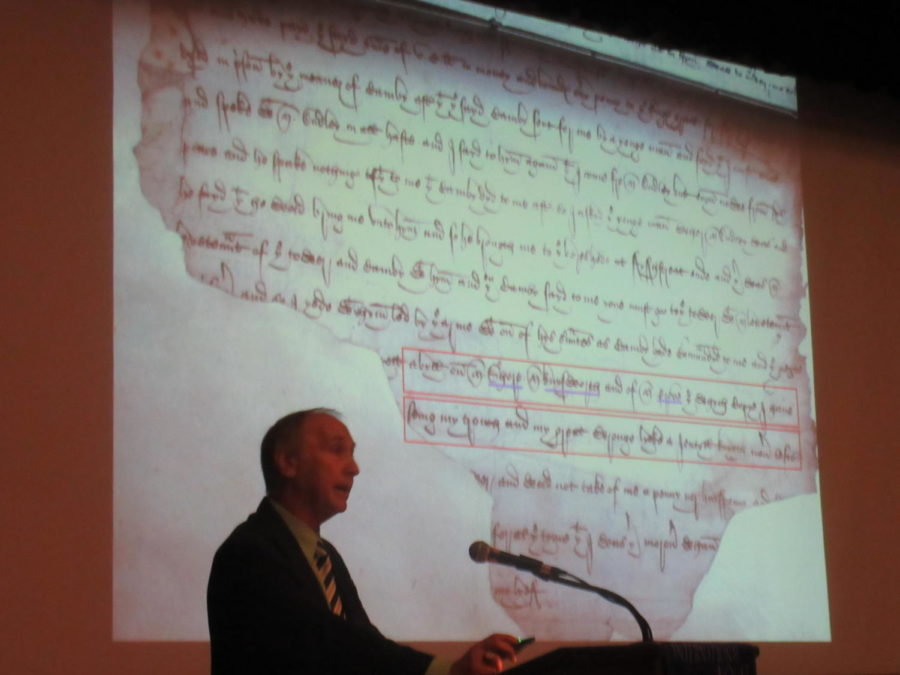

Horowitz reviewed other documents belonging and pertaining to Dudley. Over time, he noticed a curious trend. On different documents—even those written around the same time—Dudley signed his name differently. Horowitz projected an image on the screen for all of his audience to see, revealing that, on the very same page, Dudley signed his name as both “Edmonde Dudley” and “Edmdo Dudley.” Horowitz noted that another minister by the name of Grove, who frequently popped up at the frays of Sunnyff’s story, was recorded in varying documents by two names: Grove and Greene. As Horowitz explained to his audience, people writing during this time often changed spellings. They inserted the letter “e” and replaced certain letters with others that shared a similar shape in script. In other words, there was no standardization in spelling, complicating Horowitz’s research.

After fleshing out the Sunnyff of “The Complaint of Thomas Sunnyff Against Camby,” naturally, the next figure Horowitz had to identify was Camby. As it turns out, John Camby worked under Dudley (in effect as his henchman), assisting with matters pertaining to bonds. After years of tracking, Horowitz unearthed even more information about this suspect character. A man by the name of Canby owned a brothel near the Thames. In fact, Sunnyff housed one of Canby’s prostitutes.

Damston was this very prostitute. Horowitz theorizes that she worked for Camby until she became pregnant and was, so to speak, out of commission, departing to live with a kind Christian couple and their family: the Sunnyffs. A possible explanation is that Camby, upon hearing of a child dead in the river, assumed it was Damston’s and blackmailed her into testifying against her hosts so that Dudley and Empson could leech £500 out of a wealthy merchant and give it to the king.

“The Petition of Edmond Dudley,” written the year Dudley and Empson were both executed for corruption, confirms this theory. In this petition, Dudley itemized each and every person he wronged in charging bonds. Horowitz encouraged the audience to read Dudley’s 76th entry aloud and in unison. It cites an innocent haberdasher from Ludgate charged £500—a man by the name Simmes. This bizarre and unfamiliar name would prove challenging to reconcile if one did not remember this fact: in written script, “u” with was frequently exchanged with “i,” “n” with “m,” and “f” with “s.” Go ahead, make the conversion.

This practice of randomly incarcerating and unjustly charging wealthy citizens in order to secure bond payment for the king was frighteningly common in Tudor England. The innocents submitted and paid while the judges watched. Just as common as this practice, moreover, was the equally repulsive custom of dumping unwanted, murdered infants into the Thames.

Horowitz ended his complicated (and admittedly gimmicky) presentation with an ominous side-by-side comparison of 1500 and 2015, paralleling the implications of Henry VII’s 1495 incarceration laws with modern counterparts like the Patriot Act, “sneak and peak” searches, and the omniscient eyes of Google and the NSA. In essence, history repeats itself and the wheel keeps turning.

Horowitz pushed further, saying sarcastically: “Some might argue that much like the Wars of the Roses, 9/11 was such an awakening in America of national threats to our wellbeing, but assaults on the laws and rights of people, as it began in early Tudor England, could never happen in America…right?”

So who murdered the child? Did Sunnyff actually enact the deed? Was Sunnyff the true father? Did Camby himself kill the infant? Was there an unknown party? Though many audience members, who had earlier recorded their guesses on the back of their chart-filled pamphlets, succeeded in rooting out the murderer, the answer will not be revealed here. But was the murder even the real case here?

Needless to say, the lecture left attendees with a departing thought—that, in the end of this very peculiar tale, the murderer did not turn out to be the true villain.

This event was co-sponsored by the Alumni Club of Chicago and the International House Global Voices Program. Check out their webpages for upcoming events.