Last week, an interactive exhibit called My Immigration Story on display in Reynolds Club invited students to delve into their family histories and share stories of how they, or their ancestors, arrived in the United States. The exhibit was organized by New Americans, a civic engagement project at the Institute of Politics that aids immigrants in the process of becoming American citizens.

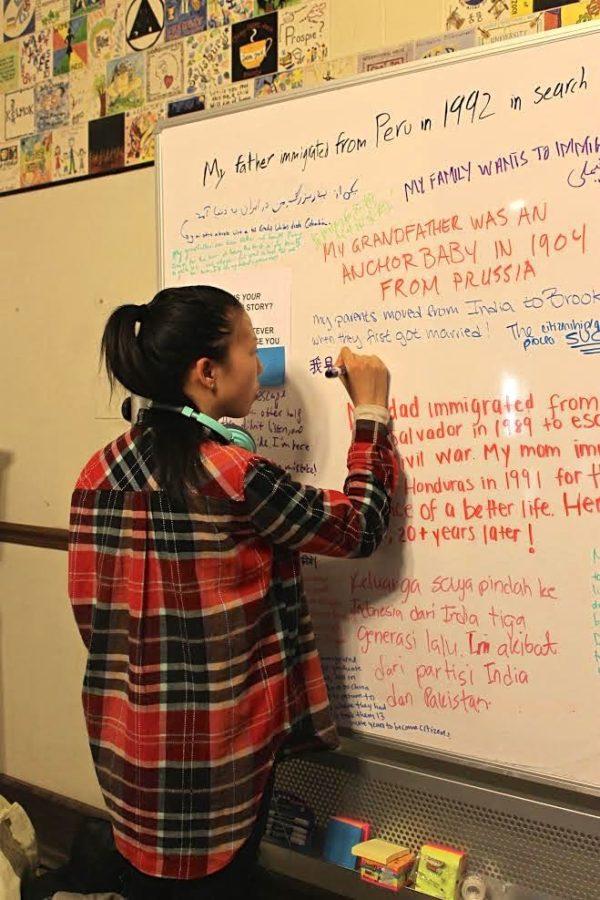

Throughout its time on display, the six-foot whiteboard stationed outside C-Shop filled up with colorful anonymous messages scrawled in dry erase marker or posted on sticky notes. Students told stories of families torn apart and reunited, relatives who fled civil wars, poverty, and struggles for citizenship that lasted decades.

Second-year Daphne McKee, who organized My Immigration Story, explained the purpose of the project.

“I intended for this exhibit to raise awareness of the importance of immigration networks and stories to the UChicago community, but I also wanted more people to know that resources for undocumented students exist at UChicago and to know about New Americans,” she said.

Some of the stories articulated the often-painful process of acclimating to a new life.

“My dad left one kind of violence in El Salvador and found another, much more sinister kind here,” read one sticky note affixed to the board.

Another participant in the exhibit wrote, “My parents came from rural Mexico. They traded one life of poverty for another.”

“I boarded a plane; the rest has been a living hell,” was the message scribed in another corner of the board.

Other stories expressed admiration and gratitude for ancestors who took great risks in search of a better life for their families.

Wrote one student, “My grandfather got a scholarship to leave Pakistan and study to become a professor in plant biology—he left a wife and 2 children behind to come study here…. We made it in America b/c of him. Love you, nana.”

Second-year Elaine Yao, the director of New Americans, elaborated on the organization’s mission of helping immigrants jumpstart their civic lives.

“Naturalization is an incredibly lengthy and demanding process. On top of having incredibly strict eligibility requirements, it requires the filling out of a very long (and expensive) application, a background check, being fingerprinted, and obviously undergoing an interview that tests your English abilities and your knowledge of U.S. government and civics,” said Yao.

“That’s where we come in,” Yao continued. “Our main community partner, the Instituto del Progreso Latino, runs classes for applicants who need help preparing for their interview and test. We act as tutors in these classes, working one-on-one with students to help them develop their language skills, give them individualized attention, and conduct mock interviews.”

The exhibit received positive reviews from those who viewed and participated in it. Its stories of hope and strife from around the globe resonated with many students and faculty.

“I think it was amazing how intimate the experience of writing on the board was,” said Yao. “Standing at the board could make you feel really vulnerable and exposed…. The most moving thing was watching someone you didn’t know stand at the board very introspectively with a marker in their hand for a while, and then look around and start to draw strength from the other messages and stories that had been written. Then they would write something down and promptly disappear.”