I, like any good Daily Show fan, was glued in equal portions to both my phone and the television screen in late July, knowing the screen time I had with host Jon Stewart was steadily ticking away. Leading up to the finale, I had been obsessed with watching every episode that aired, then subsequently going online and reading review after review, listicle after listicle, and eyeing GIF sets after GIF sets—all things Daily Show. So it was inevitable that I would come across former Daily Show correspondent and writer Wyatt Cenac speaking on comedian Marc Maron’s podcast, WTF.

Something that Cenac said really stood out to me: “I was the one black writer there…It was this thing where, when you’re the one, whether you want to or not, you wind up speaking for everybody. You speak for all the black people but you also—at least for me—I just speak for all the minorities because no one’s speaking for them when something seems questionable.”

Even though my throat clenched and stomach dropped knowing that such a great host had done such a not-so-great thing, I felt relief and found a kind of peace in Wyatt’s insight. I realized that I too act—or don’t act—based on this line of thought every day, and I have been doing so for as long as I can remember.

There’s this notion at this school that there exists some “They—”, some faceless party that represents the powers that be; this could be the University, the admissions office, Dean Boyer, etc. And “They” are the ones who decided to admit you here. There are reasons why “They” decided on you and not someone else, and things like race or income become obvious factors to explain why an individual might have been chosen—to promote diversity.

That’s fine. I get that. But somehow, this doesn’t seem to be true. Yes, a large part of this campus’s diversity might serve to fill some silly quota or exist for marketing purposes. These probably are a couple of the incentives for increasing diversity, but it seems that there’s a true interest in cultivating and generating discussion (all of that “Life of the Mind” jazz) and, more importantly, in engaging with people who have worldviews that differ from yours. For that to happen, the University actually has to bring people from a wide range of backgrounds. The problem isn’t that minorities aren’t represented, but is that the people representing those minorities actually have to speak for diversity to exist. At times that part gets tricky.

I read a lot of Facebook statuses, for example, about the current environment on campus, and many students are very critical of the University and its initiatives to provide support for students from marginalized or disadvantaged backgrounds (i.e. students of minority races, lower income students, and first generation college students). These people often have valid points, and I certainly don’t mean to devalue them in any way, but they don’t always speak from firsthand experience. It’s hard for someone like me—an actual minority—to even chime in. My desire to participate in these conversations is often outweighed by my lack of comfort. I don’t know how to enter this conversation that I should be a critical part of. Because when I do participate, it’s just like Cenac said.

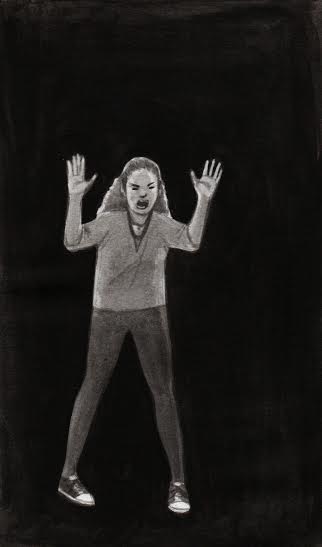

When I do participate, different problems arise. Like what Cenac experienced on The Daily Show, I have suddenly become the spokesperson for minority races in general (not just mine) too often because I have quite obviously been the only minority present. In these situations, I always feel overwhelmed and hesitant to speak just for the sake of the discussion. I feel a need to be completely informed about all aspects of race and to account for the many series of half-steps, missteps, and potential digressions from the path that we may end up going down.

When you’re reading Fanon and happen to be the only black person in the room, suddenly you’re no longer just another student. Instead, you’re an expert on all aspects of race and the class is looking to you for answers. I’m always asking myself questions like “What will I say?”, “What will it say about other people who identify similarly to me?”, and “Will I be making widespread generalizations since my thoughts are based on my experiences alone?” Answering these questions is incredibly crucial to meaningfully add to the overarching dialogue. But that’s a lot of responsibility for just one 19-year-old college student. While I enjoy talking about race, it does get exhausting to have to explain, from the perspective of the individual, what it’s like to identify with a monolithic collective.

It’s important to highlight these fears because I think most people who identify with a minority group approach discussions like this. They are forced to take extra cognitive steps before commenting for everyone in their race in order to make the overall conversation more well-rounded or accurate. Conversations pertaining to identity, especially identities that are typically institutionally disenfranchised, are incredibly important, but these conversations are missing something when the very people who are directly affected are afraid to speak out of fear of misrepresentation. It’s obviously ideal for classrooms to be more diverse so that we can have a more nuanced discussion about race with multiple people from multiple backgrounds, but for now, there is usually one lone minority voice in a 20-person SOSC class. Although it’s a lot of pressure, and although it can be difficult to navigate, that one minority has to push through their fears and speak out. Their point of view is essential to creating a well-balanced and diverse discussion. Unfortunately, as Cenac said, they will feel the need to “speak for all the minorities because no one [else is] speaking for them.” That’s hard—maybe even impossible. We should start by speaking for ourselves. Speaking for an entire group of people doesn’t create diversity anyway; it creates an illusion. Recognizing the diversities within diversity might be the real challenge.

Kanisha Williams is a second-year in the College majoring in political science.