[iframe src='//cdn.knightlab.com/libs/timeline3/latest/embed/index.html?source=1a-xaa6QDKa6tGSSIAUereSRin6EZph2m4m3lJMoeMYw&font=Default&lang=en&initial_zoom=2&height=650' width='100%' height='650' frameborder='0']

UChicago and Sinai Health System are bringing a Level I trauma center to Chicago’s South Side.

Last month, Sinai Health System and the University of Chicago Medical Center (UCMC) announced a joint partnership to create a comprehensive network solution that will provide Level I trauma care (T1) services to Chicago’s South and Southwest neighborhoods.

The creation of a state-of-the-art T1, an expansion of Sinai's Holy Cross Hospital at 68th and California Avenue, will aim to curb trauma and gun-related mortalities. This news comes after years of tension between students, community members, and hospital administration. In June, a demonstration involving lock-in-tactics ended in the arrest of nine activists.

What concerns do community members still have about the proposed new trauma center? Furthermore, what are the physician and administrative responses to those concerns? The Maroon investigated these basic questions surrounding the complex, ongoing issue of trauma care on the South Side.

How the Partnership Began

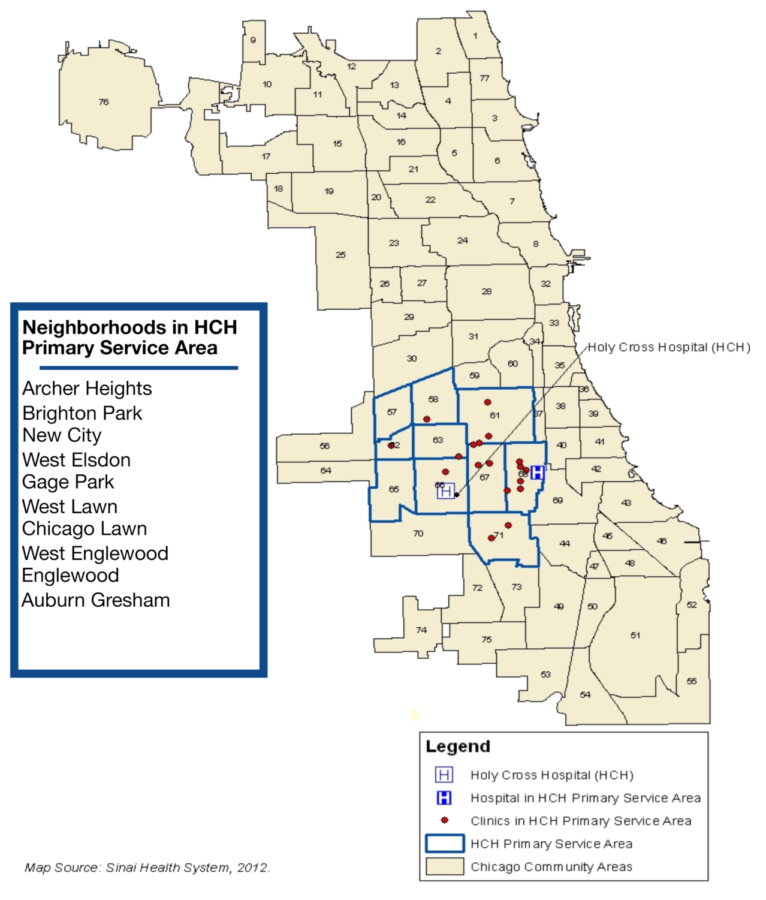

“We were looking at more traditional service data first, but the trauma data really just popped out at you. It was impossible not to be drawn to where the trauma was coming from, and it was a really big cluster around the Holy Cross community,” said Karen Teitelbaum, CEO and president of Sinai Health System, as she detailed how the idea to collaborate began in late spring of this year. After considering input from town hall meetings with community members and an awareness of UCMC’s relationship to trauma care, Teitelbaum contacted President Sharon O’Keefe of UCMC, and relayed her interest in establishing a trauma center at Holy Cross.

Seeking a network solution to begin with, O’Keefe said she felt the partnership was a natural choice. “We were extremely excited about the partnership with the Sinai Health System…and over a course of 8 to ten weeks, we came together and worked out the major elements of the partnership going forward,” O’Keefe said.

Though the UCMC and Sinai joint T1 talks started in the spring, they weren’t announced publicly at the time because, according to O’Keefe, the UCMC board, Sinai Health System Board, and university representatives were required to agree on partnership criteria before public release of the talks could be done on good principle.

The Community Response and Concerns

Longtime South Side resident, President of Medical Students for Health Equity, and fourth-year Pritzker medical student Abdullah Pratt spent much of his childhood in the Woodlawn area and had grown accustomed to the impact of violence in the South Side, especially after his brother was killed. He saw this push for a systems-level solution as a step in the right direction from both UCMC and Sinai.

“Putting the community members first was the objective [of UCMC and Sinai]. It was a demonstration in looking at problems that face the community that have no easy solutions. Trauma has no easy solution,” Pratt said, emphasizing that a partnership solution between two hospitals in the South Side represented an unconventional approach to a familiar problem. “Finding a solution out of the box throughout the community is what it’s really going to take to solve many of the healthcare issues, whether it be diabetes, asthma, cancer, and other chronic diseases, trauma care included in that.”

As Holy Cross is situated close to several of the highest crime neighborhoods, Pratt believes the trauma center will go a long way towards reversing the trauma desert currently plaguing the South Side. “Some of the most violence-ridden areas, such as Englewood…which is a huge area, directly east of where the trauma center will be built, will be helped,” Pratt said, though he also expressed some concern that neighborhoods further east will still have to travel far to reach a local trauma center.

However, not all community members agreed with Pratt’s overall positive reaction to the UCMC-Sinai partnership.

“I went through a roller coaster of emotion. I was angry because [UCMC] didn’t consult with [TCC]. Kenneth Polonsky, Derek Douglas, they had an opportunity to at least let us know that something was being done. But they didn’t want our opinion,” said Veronica Morris-Moore, a long-time community and youth organizer for Fearless Leading by the Youth (FLY) and the Trauma Center Coalition (TCC). She does not believe UCMC would have moved to expand T1 coverage had it not been for black youth protests, arrests at demonstrations, and time spent raising awareness about the lack of a T1 center in the South Side.

Furthermore, she remarked that the location of Holy Cross did not make sense to her. “If you can do it at Mount Sinai, why can’t you do it at [the] University of Chicago? [Holy Cross] is closer to the trauma center at Advocate Christ than it is to South Shore [neighborhood] that has some of the highest trauma related deaths in the South Side,” Morris-Moore said.

Regarding distance, she expressed concerns that many of the highest gun-violence neighborhoods will still be outside a five-mile radius from Holy Cross Hospital, citing a popular study done by Northwestern which concluded that mortality increased for trauma patients outside a five-mile radius from the nearest trauma center. Finally, due to high resource demands, she also worried that the building of the new Level I trauma center at Holy Cross will result in the withdrawal of UCMC’s proposed plans to raise Comer’s pediatric T1 age to include 16- and 17-year-old children, which was announced last December.

According to Sharon O’Keefe, the application to the Illinois Department of Public Health (IDPH) to raise the pediatric age at Comer’s Level I trauma center will not be withdrawn, nor will the proposal of raising the age require a capital investment. The request is still pending review at IDPH, though O’Keefe stated that, as the new partnership will mitigate some of the need for the raising of the age at Comer, the predicted services provided by the trauma center will affect the IDPH’s decision to approve or reject the application.

Despite their concerns, Morris-Moore and other protestors of the black youth community are proud of the announcement to build a new Level I trauma center as a tangible result of their sacrifice. “It’s a victory. Nobody can deny what people who are in our position made happen, whether people say it or not,” said Morris-Moore.

Physician Responses to Community Concerns

“We discovered that we could do more when working with the Sinai System at Holy Cross than either of us could have done separately. This is a perfect example of an honest-to-goodness synergy,” said Dr. Doug Dirschl, chairman of the Department of Orthopedic Surgery and Rehabilitation Medicine at UCMC, emphasizing that collaboration, and not which institutions will be contributing what personnel, is the key to the success of this trauma center.

“This will become one of the busiest [hospitals], if not the busiest, in the area of Chicago,” Dirschl said, though he cautioned against any predictions toward the capacity of the new trauma center.

Dr. Gary Merlotti, chairman of the Department of Surgery at Sinai Health System, corroborated Dr. Dirschl’s emphasis on the importance of the collaboration, and believes that each institution’s strengths will complement the other to allow for a high-functioning T1 center. According to Merlotti, the University of Chicago only has expertise in managing pediatric trauma, not adult, while Sinai has had over 25 years of experience in overseeing such an operation. Furthermore, the current configuration of Holy Cross doesn’t lend itself well to treating some forms of trauma due to restrictions in space and the lack of conveniently located rapid services related to trauma care, which will be addressed as part of the $41.3 million provided by UCMC. “In addition, we [at Holy Cross] don’t have enough of, nor high enough quality of, subspecialties services to meet the trauma patient’s needs,” Merlotti said, emphasizing that UCMC will aid in supplying needed subspecialists.

Both Merlotti and Dirschl expressed concerns that too much emphasis has been placed in the media on the “five-mile radius” rule. Merlotti, who has over 35 years of experience in trauma care and was one of several architects of the Chicago Trauma Network in the mid-1980s, feels that using this rule to assess the future efficacy of the new T1 is inherently flawed. “[Five-mile mark] is a completely empiric number and highly debatable as to whether or not it’s of any significance,” Merlotti said.

Concerning the Northwestern study that defined the five-mile radius rule, Merlotti said that no further studies have been able to replicate it, and that the key factor when it comes to trauma isn’t distance to a hospital, but the severity of trauma and the total time injured. “It’s interesting that if you look at the data at seven miles, as opposed to five, it doesn’t make a difference [towards trauma mortality].” Merlotti said.

In a previous edition of The Maroon, we analyzed several studies which demonstrated that scene time, or the time EMS is at the scene with the patient until the patient is transported, and trauma severity, but not transport time or distance, impacted mortality of penetrating trauma. According to a 2013 study done by McCoy et al., in the Annals of Emergency Medicine, if scene time was 20 minutes or more, patients were much more likely to die.

Given that McCoy et al. found that median ambulance transport times were 12 minutes for all cases of blunt and penetrating trauma, a rough estimate of a trauma center’s radius of coverage can be estimated within a range of ambulance speeds.

In addition to the new T1, the initiative includes the creation of a new state-of-the-art emergency department at UCMC, which will aim to expand available services to the South Side communities closer to Hyde Park. According to Phil Verhoef, an ICU Pediatric and Adult physician, the expansion of the ED will go far toward adjusting to the patient load that UCMC handles at the ER each day. “I’ve been a patient in the ER and, as it is now, there’s hardly any privacy; Mitchell Hospital can’t handle the volume it receives, and it has outdated technology. So, this is very much needed,” Verhoef said.

What are the next steps?

Amidst the hype of a joint, systems-level approach to the trauma desert on the South Side, the proposed Holy Cross Level I trauma center and the new adult ER still require regulatory approval through the filing of a Certificate of Need (CoN) application with the Illinois Health Facility and Services Review Board.

“In addition, [Holy Cross] will have to achieve Level I designation by IDPH. That will probably come a little bit down the road. It’s hard to get them to approve a trauma center that doesn’t yet exist,” Merlotti said, when asked about what still needed to be done before construction would begin. At the earliest, approval processes and construction are expected to take at least two years. During that time, both Sinai and UCMC will recruit additional staff and healthcare professionals to bolster the needed personnel to operate the endeavor.

Despite criticisms made against UCMC, O’Keefe believes that expanded emergency services at Holy Cross and UCMC will be invaluable to the South Side. “We’re aware that some people have different vantage points on this, but the value that [this partnership’s] bringing to the South Side is absolutely tremendous.”

Morris-Moore expressed caution in celebrating too early, elaborating on the need for student and community members to make sure that the Level I trauma center will operate at the expected level. “We’ll keep fighting to make sure that the University does what it says it’s going to do. We want to make sure that, not only does this trauma center get built, but that it’s a quality trauma center. That it saves lives,” Morris-Moore said. “That’s what the community deserves and needs.”