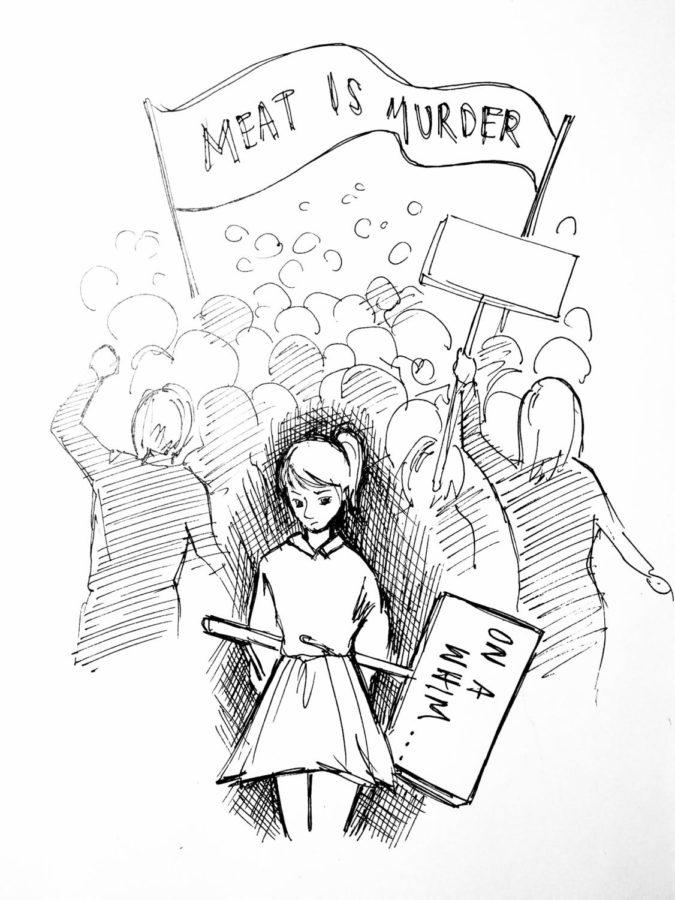

When I was eight, I decided it would be funny if I stopped eating meat. I don’t remember why the idea struck me as being so comical, but I do remember that I found it funny enough to tell my parents over dinner that I was renouncing meat forever. My parents didn’t get the joke (my mother thought it was a not-so-subtle judgment of her cooking), but the fact that I believed I could actually pull it off for longer than a day was apparently hysterical. Laughing heartily, my parents told me I’d only be a vegetarian between meals. I viewed that as a challenge.

I didn’t eat meat for another ten years.

Overnight, I was inducted into the cult of vegetarians. What I had thought would be a simple refusal to eat meat quickly evolved into much, much more. I found fellow vegetarians everywhere. I’d be standing in line in my high school’s cafeteria and the person behind me would ask why I’d refused the chicken nuggets —was I also a vegetarian? I’d ask if there was a vegetarian option on a plane ride and two or three other passengers would all chime in at once I met other vegetarians so frequently that I wondered if it wasn’t some massive conspiracy.

Once introduced to a fellow vegetarian, conversation invariably turned to why I chose to stop eating meat. I learned that when it comes to vegetarianism, motive is everything. Saying that I made the choice to spite my parents was generally met with awkward silence or forced laughter. It was like telling a born-again Christian that you went to church because you thought the building was pretty. I had to adapt to fit in. I began to cite all the compassion I felt for animals, how I couldn’t bring myself to devour them anymore. While I did love most animals, this wasn’t an entirely honest reply. I found chickens terrifying and I was convinced that fish were evil (this is an indisputable fact). I don’t exactly empathize with cows. Hamburgers are delicious, after all, but live bulls can kill you. Nonetheless, my fake empathy for the entire animal kingdom struck a chord.

As I grew older, my answers became more sophisticated. I was a vegetarian because I loved animals, yes, but more importantly, I loved the planet. I’d go on about how the meat industry was killing the earth. I’d talk about methane emissions from cows and the amount of water it takes to process meat. While none of this was why I’d become a vegetarian, I began to think it was why I’d chosen to remain one. My fellow vegetarians found these answers satisfying and I became a “real” vegetarian at last, revelling in my moral superiority while my meat-eating acquaintances unwittingly killed Mother Earth, one strip of bacon at a time.

To be clear, the meat industry is bad for the planet, and loving animals is a great reason to not eat them. The problem is that ethical considerations are often used as motives to brag about certain choices, like vegetarianism, rather than legitimate reasons to make those choices in the first place.

I used to only joke that being a vegetarian was like being a member of a cult, but I was beginning to realize that I was more right than I’d thought. The worst part was that all the extremely ethical reasons I cited in clinging to vegetarianism were starting to look like excuses to be obnoxious, instead of genuine concerns. I really liked the feeling of belonging to a small, exclusive club of people who could say they ate ethically. I memorized facts about why meat was bad. I flirted with veganism, because vegetarianism didn’t seem extreme enough. I had once been annoyed by those vegetarians who would remind you at every opportunity that the stuff on your plate used to be alive; now, I was one of them. I was using every opportunity to remind people that I was a vegetarian, but like most cult members, I liked the feeling of belonging to a small movement. I didn’t want too many people to become vegetarians, because if if everyone made that choice, I wouldn’t be special anymore.

This fear was realized when I went on a backpacking trip and discovered that precisely one third of the trip was vegetarian. My dietary preference was very nearly a dietary norm. This was profoundly unsettling for me. How are you supposed to act morally indignant when everyone agrees with you? The entire experience was akin to a hipster waking up to find his favorite obscure band has gone “mainstream.” The horror!

A few weeks later, I did some reluctant soul-searching over tofu. I came to several realizations. Chief among those was how much I hated tofu. But I also realized that, like many vegetarians, I had always thought in the back of my mind that by being a vegetarian I could make myself a champion of cows, poultry, and fish. But once I began to really think about it, I realized that I despised fish, and couldn’t for the life of me figure out why on earth anyone would want to be known as a salmon savior. As a vegetarian, I’d never been anything more than someone desperately looking for an opportunity to pat themselves on the back. It was moral vindication and not animal lives I’d been campaigning for.

This isn’t to suggest that all vegetarians are like that; most of them object to eating animals for a genuine and legitimate reason. But it is all too easy to forget good intentions entirely as you congratulate yourself for your exemplary ethical standards.

When I found that my motives for a decade of vegetarianism were morally suspect, I decided I didn’t have to be one anymore. I quit the very next day. I had been a vegetarian for over half of my life. The last time I had eaten meat, I couldn’t spell “desert,” and memorizing times tables was by far the greatest achievement of my life. Now I found myself at a restaurant about to order meat. After ten minutes of agonizing deliberation, I got a hot dog.

Like everything else on the menu, it tasted like cardboard.

Natalie Denby is a first year in college majoring in Public Policy.