On the last Friday before winter break, campus was eerily silent yet heavy with anticipation. Whether we were getting on a shuttle headed to the airport or still in a Reg cubicle typing out that last paper due at 11:59 p.m., our minds were on the smells, tastes, and feelings of home. We’d be there soon.

When I stepped through the doorway back into the house I grew up in—the living room where I built my first papier-mâché diorama for science class, the kitchen where 10-year-old me burned a cake following a self-created recipe that called for gummy bears—a transformation occurred. I was no longer a college student struggling on the cusp of adulthood. All the layers of development that I thought I had achieved melted away so easily into the bratty kid that was apparently still dormant inside of me.

No matter how much I manage to delude myself into believing that I’ve matured as a person, I know that I still have a long, long way to go whenever observing my behavior at home. I’ve noticed that even though it feels easy for me to be patient with a friend or to help them out, I’m markedly less considerate to my parents when I’m with them. In fact, my home-self is probably a much truer indication of who I am inside than the self displayed in front of my friends.

This odd regression into immaturity when returning home seems to be a phenomenon portrayed everywhere from novels to movies. In the show Master of None, the main character Dev repeatedly refuses to help his father set up a tablet computer even though it would take only a minute, just because he is eager to spend time with his friends. As I watched that episode, I could feel a guilty pit forming in my stomach. Why is it so easy for us to be one way in public but another way to the people who love us the most?

Maybe it has to do with just that—the fact that, for many of us, the love of our parents is as close to unconditional love as is humanly possible. At least for me, I know that even though I can disappoint my mom or make her angry, I can never make her stop loving me. I don’t have to earn something that I already have so securely, making it easy to take our relationship for granted. On the other hand, with friends, no matter how close they seem, I still feel as though I need to constantly prove myself in order to maintain their affection. I know that there is a certain limit to the terrible things I can commit before they peace out.

That’s why going home is a reminder of how much more I need to mature as a person. Outside this private sphere of family, our kindness towards others is frequently less genuine and more from ulterior motives to benefit ourselves. Even treating an enemy well often comes from the desire to reconcile a relationship. These are all necessary components of life, but this environment might cloud our assessment of who we really are. Home lessens such incentives due to the love that we have as a birthright.

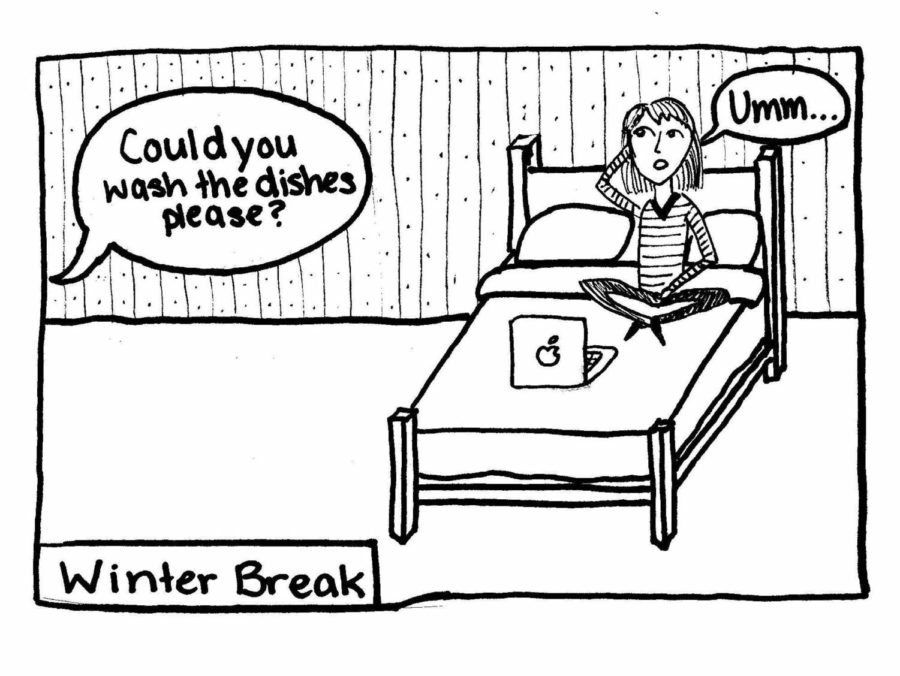

There are definitely harmless perks to not having to put up a front while at home for break, like getting to walk around all day with bedhead or being able to do embarrassing exercise videos without locking all our doors. But if not our outer beauty, maybe our parents deserve our best foot forward when it comes to inner beauty, like helping around the house more or just having open conversations with them. Especially when they seem to pull out all the stops for our homecoming, from cooking our favorite meals to doing all the dirty laundry we collected during finals week.

For me, I’ve realized that I need to be more considerate at home in order to truly grow—not just seeming to do so on the surface. I want to become a person whose actions are less dependent on how something benefits me. Meanwhile, I can only feel gratitude toward my parents for accepting me despite all of my immaturity, which shows that deep down, I’m still just a kid—their kid with bedhead.

Sophia Chen is a second-year in the College double-majoring in economics and English.