Every holiday season, people face a dreaded situation in households across America. The possibility that it could happen to you or someone you know is terrifying enough to justify a deluge of tips on how to avoid it. Advice columns mention it as if it were as bad as the plague. I refer, of course, to the only sure-fire way to kill the holiday spirit: talking politics with your extended family.

It isn’t a topic I gave serious thought to before now. My extended family is divided on either side of the political spectrum, so each holiday season we become masters of avoiding any subject that could offend. Whenever a remotely political topic is brought up, the speaker is dealt a dirty look, and then the conversation quickly moves on to something safer: how much we hate shoveling (a lot), how good dinner is (debatable), how that sister still hasn’t forgiven you for ruining Santa 12 years ago (let it go, Ali). How boring the conversation is doesn’t matter, so long as no one has to suffer through the apparently unbearable realization that not everybody is in agreement with each other all the time.

Until recently, I agreed with this idea. Why would you want to pick a fight when you could just as easily avoid one? My views began to change after my family had a distant relative over for dinner a few weeks ago. Being extremely conservative, it wasn’t long before she brought up Donald Trump. Her efforts to discuss Trump were met with our usual approach: we tried to change the subject. But somehow she always found a way to segue back to Trump. For example: “No snow this year? Liberals are going to make that seem like proof of climate change, but I heard in a Trump speech… ” We found ourselves smiling stiffly, everyone offended by something she was saying and dying to interject. But we all knew that politics is a dirty topic, and the only way to discuss it with someone who disagrees is to get into a screaming match. How can you be civil when you’re hurling insults at one another? Eventually someone brought up Star Wars, and peace was salvaged.

But by not saying anything, we allowed her to leave believing that we agreed with her, effectively making ourselves liars. And as far as we were concerned, this was okay—better to be fake Trump supporters than to get into a fight.

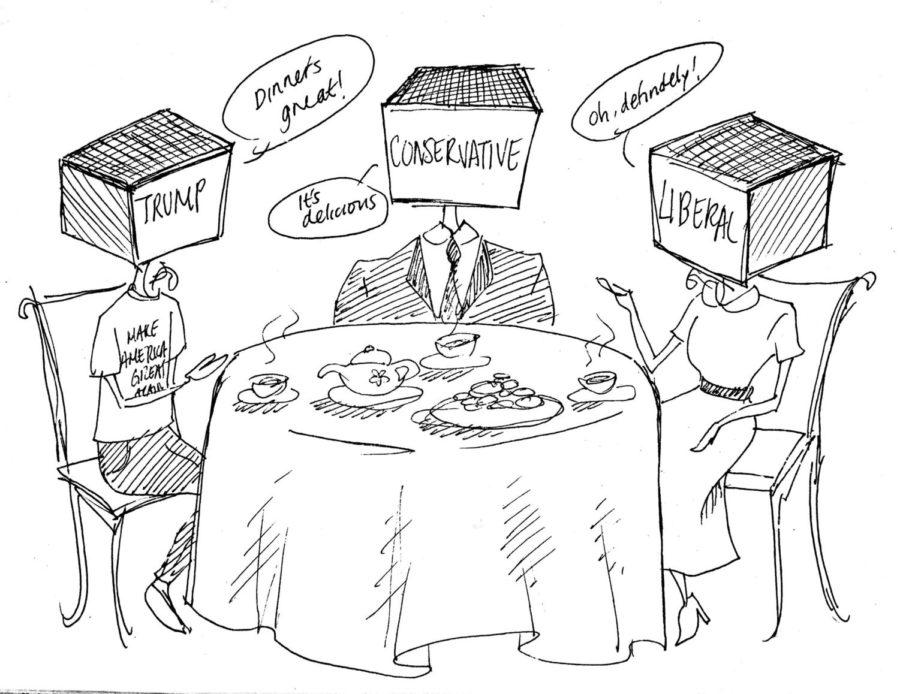

This kind of avoidance is not just typical of my family; stark and uncompromising dichotomies are becoming the norm of political discussions. For some reason, Americans seem to believe that the only way to talk about politics with someone on the other side of the aisle is to try to rip them apart, limb by limb. It’s as if the word “government” is infuriating enough to drive the average person into a bloodthirsty frenzy. But whatever happened to civilized discussion? The result of this cultural taboo is that we’ve become incapable of reaching across a political chasm, whether it’s at the dinner table or in Congress.

But if we restrict ourselves to talking with people who agree with us, we run the risk of leading our lives in an echo chamber. Refusing to talk about something unless you know you’re talking with someone who agrees is almost the same as not talking at all; you get nothing meaningful except the chance to become more rigid in your beliefs and less willing to listen. We need to realize that the only way to find common ground with people who disagree with us is to talk to them. Otherwise, we risk becoming comfortable with a state where political discourse is limited to either silence or shouting––nothing in between.

So next holiday season, when it looks like your Republican uncle wants to butt heads with your liberal great-aunt, don’t change the subject. Don’t nod politely, but don’t shout, either. Talk but know that you don’t have to win someone over. A good conversation doesn’t necessarily end with your great-aunt joining the Tea Party or your uncle lying in a bloody heap on the table. It’s okay if you leave dinner believing you’re more right than ever. Worse comes to worst, your family brawl goes viral. You could be famous.

Natalie Denby is a first-year in the College majoring in public policy.