While other kids deal with pimples and first dates

I will teach them how to act around police officers.

We will sit down and have the talk

Just like my mother did with me.

At a book release event in the Logan Center Performance Penthouse this past November, fourth-year anthropology and comparative race and ethnic studies double-major Vincente Perez unveiled his first self-published anthology, B(lack)ness and Latini(dad), a collection of 14 poems accompanied by visual artwork and a self-produced album. With over 75 copies already sold, this 6” x 9” chapbook—a small booklet—fuses hip-hop, spoken word poetry, and academic writing to give voice to Perez’s personal narrative as he navigates the classifications of black, Latino, and father.

Known for his performances at Catcher in the Rhyme showcases, downtown venues like The Gala, and various campus cultural events, Vincente “SubVersive” Perez has drawn a significant following in the past years as an artist and activist. When fans began asking for hard copies of his work in January of last year, Perez seized this opportunity to organize his poems into themes which encapsulate his identity at this phase of life. To unite his poems and allude to his interest in working in various media, Perez decided to center his chapbook on the theme of liminality, a term typically used in anthropology which designates a transitional phase in a rite of passage.

“I see liminality as not trying to find boxes that you fit in, but existing outside of them—not fitting in as its own world. Instead of seeing yourself as limited because you are between worlds, owning up to that experience. Living in it and relishing it to control how you see the world,” Perez said.

For Perez, liminality does not suggest ambiguity but, rather, conscious multiplicity. In his most well-known spoken word poem, “Check One,” which Perez considers his most challenging yet rewarding work, he tells the story of the first time he took an in-school survey. It was about adolescent drug use. It asked him to indicate name, age, and race (check one).

Only one.

Perez launches into his distressed story of a light-skinned, non-Spanish-speaking Latino who is also called a “nigga not really black.” Am I black today? Am I Latino? Am I human? He delves into his family history while critiquing the legacy of colonization and white supremacy, ultimately checkmating the “check one.”

You can see the spoken word form of “Check One” performed on Perez’s website, YouTube channel, or at his next show. The performance is powerful; the reaction, visceral. Perez laughs, twists his lips, and runs his fingers through his hair. In the recording of “War Paint,” another one of Perez’s poems, he steps away from the mic entirely, letting his shouts fall directly on the audience. In a different performance of the same poem, a dancer accompanies Perez on stage.

When each performance is more presence than lyric, how can a chapbook do the words justice? To preserve his attention to cadence, voice, movement, and shock value, Perez made several stylistic decisions when formatting B(lack)ness and Latini(dad). Perez has a field day with italics, bolding, and ellipses. He occasionally experiments with page alignment and onomatopoeia while writing a punctuation rulebook of his own. The entire chapbook—text and artwork alike—is presented in black and white with touches of red. These touches cue the reader but are no substitute for Perez in the flesh.

“Putting it on page really changes how things are emphasized. The performance aspect is taken away, but being able to use visual art adds a new layer to it,” Perez said.

Perez includes artwork from seven different artists, many from his hometown of Kansas City. Through research and a series of referrals, Perez found artists exploring ideas similar to his own, focusing on not just race, culture, and politics but a mixture of the three. Thanks to sponsorship by the UChicago Student Fine Arts Fund and ArtsKC—a regional arts council in Kansas City—Perez was able to compensate these artists for their work.

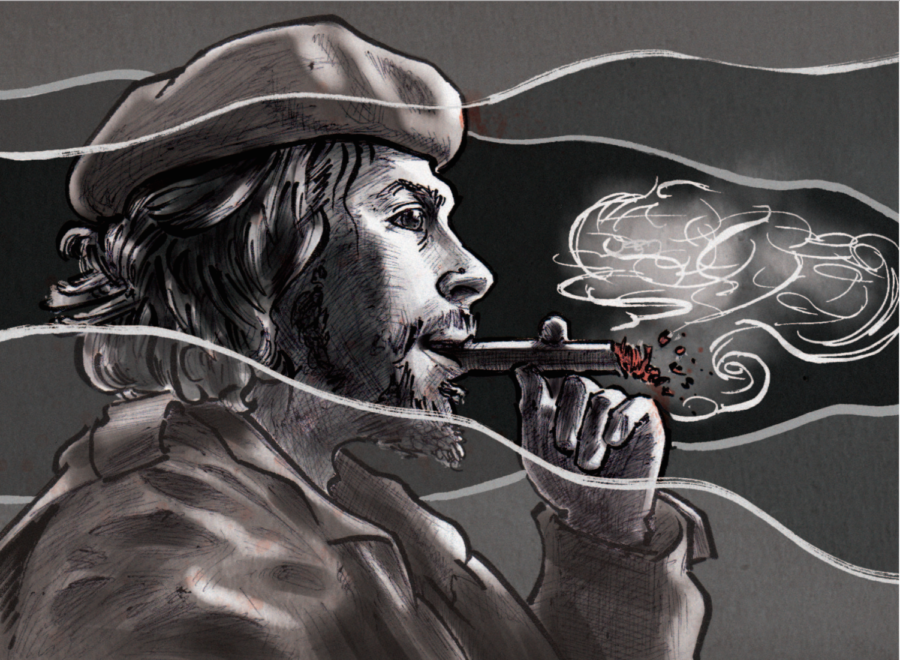

Artist Visualgoodies’ image for the poem titled “Time (I am)” is an intriguing Afrofuturist collage and the only full-color piece in the chapbook. This visual fusion of cultures and eras complements Perez’s discussion of cyclical oppression. However, some of the most stunning works included in B(lack)ness and Latini(dad) are Darren Kennedy’s war drawings, blurred by smoke and shadow. This series of four images develops a main character and plot, lending a new form of narration to the poem “¿Revolutionary?”

Not only did Perez rework his poems for their transition to the page, he further refined them through performance. Perez reads the crowd, adjusts accordingly, and rewrites. In this way, the poems themselves become liminal, existing in an in-between of print, speech, and constant evolution.

“When I first started off, I think a lot of people critiqued my work for being angry and not celebratory, and that’s something that really changed me as an artist,” Perez recalled. “I was basically stepping on a pedestal and using my art only as a political platform and not at all engaging with who I was as a person, and so my art started off very preachy.”

While anger certainly burns through many of Perez’s poems, often through a string of profanities, he balances his tendency towards an “us vs. them” battle cry with highly personal stories of childhood and family. Even in the introduction, Perez, off the soapbox, welcomes criticism and shares his own story. The first image the reader sees in B(lack)ness and Latini(dad) isn’t Kennedy’s armed revolutionary; it’s Perez feeding his two sons.

“This book was a way to heal the past, a way to interpret my past and things that I dealt with, whether it’s anti-blackness from my Latino family—not feeling like I fit in with black people on that side—or using that experience to talk about how race doesn’t exist but racism does, and what that means for multiracial youth who need to hear these kinds of things.”

“The Talk,” a poem that uses parenting as a mechanism to talk about police brutality, is one of the most vulnerable and touching of Perez’s poems. Beyond fear for his community and his own future, this work is about the immediate and helpless terror of bringing a life into this world that you cannot protect. How do you teach dignity and autonomy while praying that your sons obey cops like puppets?

Perez delves deeper into these personal anecdotes on the accompanying album. In Liminality, Perez collaborated with independent instrumentalists and producers to develop six tracks. While Perez investigates the topic of cyclical oppression in raps like “Time (I am),” which features guest bridges in the rap version, he ventures into more romantic territory with “Over Her,” carefully balancing thematic trends with new material.

Simultaneously insider and outsider, Perez engages with his unique identity to produce a work that is liminal in both content and structure. Although it may better serve as a supplement to Perez’s live performances than a stand-alone compilation, B(lack)ness and Latini(dad) explores race as both social construct and personal decision with an innovative blend of harnessed frustration, filial love, and academic reflection. Part diary, part essay, and part art, it’s not a new breed of activist anthropology, it’s the story of Vincente Perez.

For more information or to view recordings of Perez’s performances, visit iamsubversive.com.