“Where are the pickled vegetables?”

As I watched a bemused professor eye Bartlett’s lackluster rendition of banh mi (the classic Vietnamese sandwich traditionally topped with pickled vegetables and served on a baguette), I could not help but think of Oberlin College’s now-infamous cafeteria food complaint. Several Asian and Asian-American students protested their cafeteria’s Asian fare—from orange chicken to banh mi—as, one student phrased it, a “ridiculous” example of cultural appropriation, in what became another headline-grabbing episode in the nationwide campus debate on political correctness.

Should UChicago students protest Bartlett food for the same reason? According to various cultural commentators and professors writing for mainstream publications, such protesting students are products of oversensitivity in higher learning. The September 2015 issue of The Atlantic, for example, featured an iconic cover story criticizing trigger warnings with the headline, “The Coddling of the American Mind.” The media, from USA Today to the Wall Street Journal, later lauded the University of Chicago as a supposed bastion of free speech on college campuses. Professor Geoffrey Stone’s “Statement on Principles of Free Expression,” on the behalf of the University, earned plaudits for championing students’ freedoms and providing a forum for debate. Instead of neutering material, the statement promised discussion of any legally permissible idea, no matter how “offensive, unwise, immoral, or wrongheaded.”

This attitude toward freedom of speech is often seen as diametrically opposed to that of college students whose requests for trigger warnings are misinterpreted as attempts to impinge upon freedom of speech. The University’s position, in reality, does not mean we should disregard trigger warnings, microaggressions, and other additions to the social justice lexicon. Rather, the statement affirms that such terms should be acknowledged as indicators of changing demographic landscapes in college, where minority groups—ethnic, gender, or otherwise—now have access to higher education and a say in it. Trigger warnings should be brought up as discussion points rather than a means of avoiding controversial works, which only restricts the aims of higher education, as the statement alludes to in its conclusion.

However, the statement’s prominent opening example—in which the administration allowed a student group to host the leader of the Communist Party—exemplifies the students’ initiative more so than the administration’s. If UChicago is truly at the vanguard of reasserting free speech as an integral component of intellectual inquiry and learning, then it can take more steps to challenge its students rather than simply allowing them to challenge themselves. The inclusion of even one work in the Core could be the proper first step.

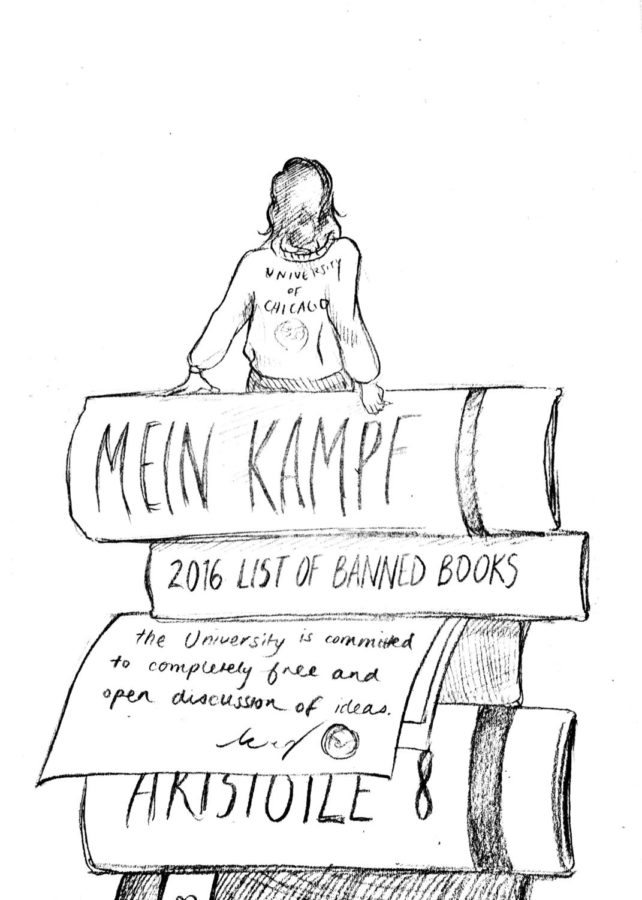

A friend recently recommended Mein Kampf’s inclusion in the Core Curriculum. Although slightly shocking at first, the more I thought about it, the more such a proposal made sense. Most students will have surely read Aristotle by their second year; in Hum and Sosc classes, the relevance of long-dead philosophers and their studied works make for vibrant discussion. Despite Mein Kampf’s nonexistent literary quality, discussing its messages as warnings can provide moving and thought-provoking conversation in the classroom, despite its obvious controversy.

When I attended school in South Florida, I had the privilege of hearing Holocaust survivors share their narratives with elementary and middle school students. Unfortunately, many of these survivors are approaching old age, and there are fewer and fewer of them left to tell their tale. Including readings from Mein Kampf (alongside complementary survivors’ accounts) therefore, could not only edify future generations of the prevalent post-WWI ideology and its grave consequences, but also allow for microaggressions as talking points. It is remarkably easy, for example, to draw parallels between the seething undercurrents of anti-Semitism in 1930s Europe with the present xenophobia central to Donald Trump’s platform or the rampant Islamophobic vitriol of Marie Le Pen’s far-right National Front party in France. If the University really wants us to come face to face with challenging material that is “offensive, unwise, immoral, or wrongheaded” without turning away or shutting down the conversation, inserting a challenged text like this in a required course would be one way for the administration to stick to its word.

Simply allowing students, then, to protest something like cultural appropriation in the dining halls isn’t enough. Because the University needs to realize that the whiny, politically correct college students lambasted in conservative and even mainstream media are, at the end of the day, still students. Teach them. In doing so, uncomfortable questions may be presented—hence the importance of recognizing trigger warnings—but by discussing them instead of dodging them, we can produce insightful answers and set an example for other campuses.

Felipe Bomeny is a first-year in the College.