Growing up, my family didn’t really follow sports. We didn’t watch football. Until about a year ago, I couldn’t have even told you what sport the Chicago Bulls play. Our only exception was cycling. My dad is hopelessly obsessed, so we all followed it avidly. Lance Armstrong was our family hero until 2012. In retrospect, it’s painful to think of how long we insisted that he was clean. The rest of the country had abandoned its former champion, but we remained among his fiercest supporters. Alleging that he’d doped was blasphemy; whenever someone accused him of cheating, we invariably turned back to our favorite refrain: Where’s the proof? And we continued to demand proof up until the day he confessed. It was inconceivable; we were more outraged and horrified than if we’d been betrayed by a close friend. From that day on, we never talked about Armstrong again.

Of course, what he did was scandalous. And in that sense, we were right to be angry. But our anger was disproportionate. We reacted to Armstrong’s admission as though we’d been told the world was ending. Our admiration for him was rooted purely in his ability to bike fast; he was just a great cyclist that we enjoyed watching. It was easy to say that a good athlete ought to be appreciated for their athletic ability, and that judging personal merit is an entirely separate consideration. But as we watched Armstrong’s downfall, it became apparent to me that we’d conflated athletic ability with character. It hadn’t been enough for us to declare that Armstrong was the greatest cyclist of all time; we considered him heroic for winning the Tour de France seven times in a row. It was as if only a truly principled and honest person could don that yellow jersey. Our baseless hero worship became painfully apparent the second Armstrong admitted to being a cheat.

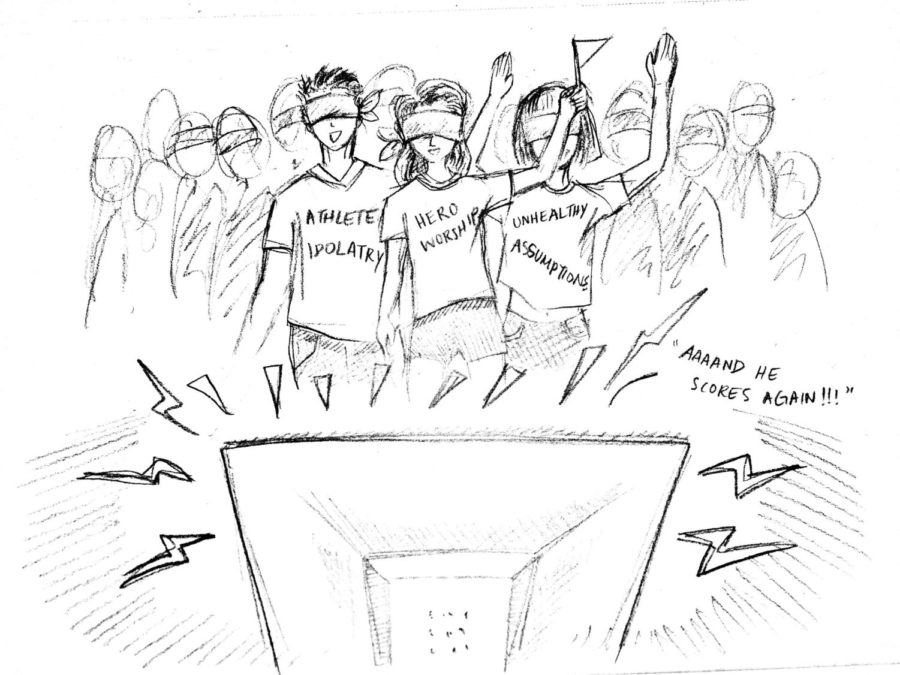

As far as athlete-worship goes, being part of the Armstrong cult was unique in that we stuck with Armstrong for way longer than most. But that’s the only unique thing about it. People are constantly finding heroes in odd places—especially in athletes and entertainers. We have a strange impulse to put celebrities on a pedestal, to regard them as being more virtuous than the rest of us mere mortals, to give them the benefit of the doubt in even the most damning of situations.

We believe that our favorite celebrities are not only good people, but are also authorities on just about everything: this is why we took financial advice from 50 Cent (who declared bankruptcy), followed the presidential endorsements of football players, and flocked to restaurants owned by musicians. It’s not that a great singer can’t also be a great cook, or that a professional football player can’t be well versed in politics; the problem is that we seem to believe that wealth and fame are likely to be accompanied by expertise in just about everything. And that’s patently false.

To be fair, our celebrity hero worship isn’t an entirely senseless impulse. There’s a lot to admire in a good athlete or entertainer––you only have to look at public figures like Jesse Owens or Jackie Robinson to understand how an athlete can leave the world substantially better. The social activism of other non-athlete celebrities, like Beyoncé, can be extraordinarily powerful.

But not all of our heroes are like Jesse Owens. A fair number are actually much closer in character to Lance Armstrong: even if they aren’t cheats, liars, or criminals, they certainly aren’t deserving of the godlike praise we heap onto them. After being betrayed by scores of athletes and entertainers we adored too much (think Bill Cosby, Manny Pacquiao, O.J. Simpson, and Joe Paterno), you’d think we’d learn to regard celebrities as ordinary people who are not exempt from the character flaws—both trivial and enormous—that plague their fellow man. Professional abilities tell you nothing about their characters. Yet we continue to forgive and defend public figures. People still adore Bill Cosby, who was immensely popular for years after Andrea Constand and 13 other women came forward with allegations of sexual assault in 2004. Even the anger we direct at disgraced celebrities is revealing—once we can no longer deny that they’ve done something wrong, our fury reveals how unreasonably high our expectations were. This is why we often regard people like Armstrong as irredeemable, not simply as athletes but as human beings.

I, for one, am not convinced by the argument that Armstrong’s doping makes him a completely vile person, especially when his charity, Livestrong, has done a great deal of good for the world. Perhaps that sort of condemnation of character is just as unfair as worshipping Armstrong in the first place: Armstrong’s crime, after all, didn’t cause grievous injury.

Our reactions to celebrities whose offenses are far more heinous, like Oscar Pistorius and Bill Cosby, are likewise revealing. Our outrage isn’t simply on behalf of the immediate victims. We behave as if we, too, are victims. And we are, in the sense that we’ve been duped. In that arena, though, we are as much the offenders as the people who’ve disappointed us. We should know better than to regard athletes and entertainers as gods, and even after it seems we should’ve learned our lesson, we choose somebody else to cling stubbornly to with unwarranted adoration. After we dropped Armstrong, it took my family all of a week to fixate on a new cyclist: Jens Voigt. Maybe our experience with Armstrong should’ve been a cautionary tale, but we couldn’t care less. As far as we’re concerned, Jens Voigt is the greatest human being on the face of the planet.

Natalie Denby is a first-year in the College majoring in public policy.