Ten days after the Charlie Hebdo tragedy in Paris, a small contemporary art exhibition opened in the city’s oldest church, St. Germain des Pres. As “Je suis Charlie” gained traction throughout the world, a quieter sub-movement emerged, embarking on an 18-month cavalcade through Europe, the Middle East, and the United States: Je suis le pont. I am the bridge.

This past Tuesday, that movement arrived at Rockefeller Chapel. The Bridge, a traveling exhibition of 47 contemporary visual artists from 15 Middle Eastern countries, celebrates the commonalities of diverse faiths. As guests munched on falafel and baklava, Rockefeller Dean Elizabeth Davenport welcomed two special guests: Ms. Heba Zaki, Deputy Consul General of the Egyptian Consulate of Chicago, and Reverend Paul-Gordon Chandler, founder and president of CARAVAN, the international peacebuilding arts nonprofit that organized the exhibition.

“This Bridge exhibition is not so much about interfaith dialogue. It’s about something much deeper: interfaith friendships. Which is much more difficult to bring about because it involves investment of yourself in the other,” Chandler said. “These art exhibitions serve as catalysts to facilitate that.”

Chandler founded CARAVAN in 2009 amidst a thriving contemporary art scene in Cairo. After the caravan completes its journey this September, forty percent of the proceeds from the exhibition—the sale of individual artworks and accompanying catalogues—will return to Cairo to support a program called “Educate Me,” an organization funding the education of underprivileged Egyptian children.

The Bridge employs art in two ways: as a physical means to bridge cultural and religious differences and as a medium for exploring the concept of a bridge. Each work was commissioned specifically for the exhibition and accompanied by an artist statement rather than a simple title card. These short essays, poems, and citations of sacred texts allow the artists to lend specific context to their visual expressions, proving just as central to the art as the images themselves.

“In my picture I have started from where all humanity has started–Adam and Eve,” wrote artist Guirguis Lotfi, born in Alexandria. “We, with our different races, religions, cultures and beliefs are all descendants from the same mother and father. We are all the same; there are no gaps between us and no true need for bridges.”

Lotfi’s fellow artists interpreted the theme in various forms: the bridge as pain, human thought, the human body, a tree, a straight line, and beyond. These bridges took shape through drawings, paintings, photographs, and one unexpected medium—volcanic sand on canvas. While some artists chose to incorporate universal symbols and blunt religious totems, several artists found clarity in abstraction, opting to represent Lofti’s theory of absent bridges with an absence of form. Lina Mowfay’s Unified Mass, for example, translates our interconnected humanity through nonfigurative overlapping paint strokes.

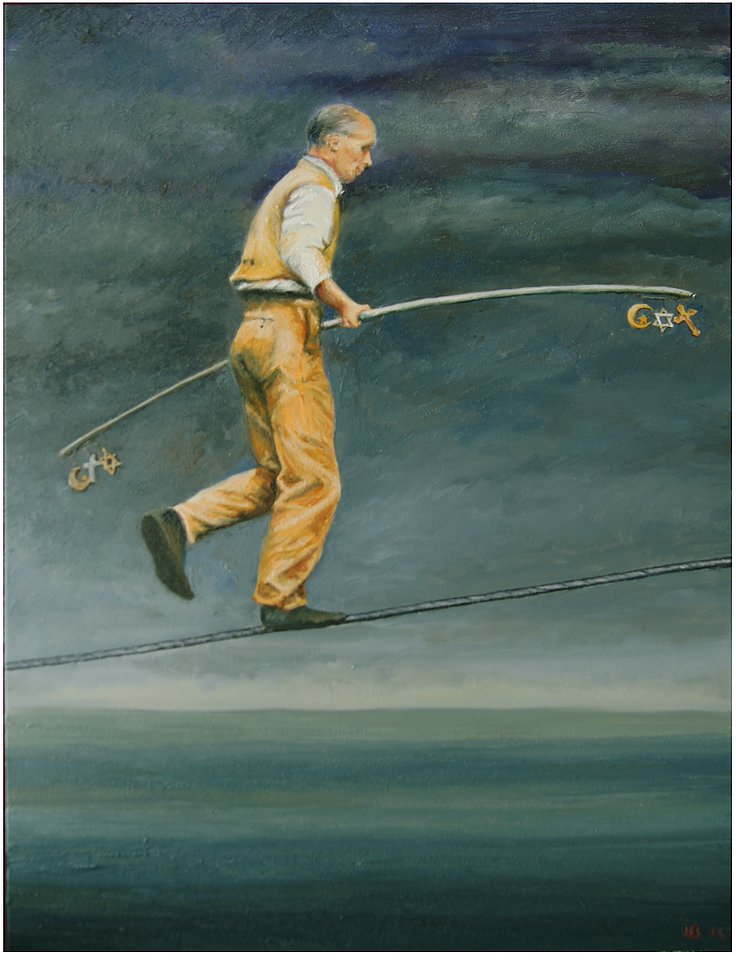

Paris-born Egyptian artist Isabelle Bakhoum bridged the gap between blatant iconography and inaccessible abstraction through figurative oil painting.

“When I was told about the theme of bridging between the Middle East and West, I immediately thought about a tightrope walker feeling his way on a marked path, challenging gravity,” Bakhoum said. “I think an artist is also someone walking a tightrope which stretches the imagination.”

In an effort to link East and West, Chandler and his team at CARAVAN strategically curated both the featured artworks and their exhibition locations. Before arriving in Chicago, The Bridge trekked through Cairo, London, Metz, and New York, catering to broad yet generally cosmopolitan audiences. But the road ahead promises greater challenges.

“We did a little survey [to identify] the most prejudiced state in the United States—anti-Arab. Do you know what came up? Wyoming. So we decided to take this right into the heart of Wyoming. This exhibition will go to four different places throughout the state of Wyoming… and a number of different artistic programs will take place around the theme,” Chandler said.

The small towns of Laramie, Rock Springs, Lander, and Powell are billed for a contentious autumn. Not only will residents have the chance to view the works of these artists, they’ll get to chat with them, too—bridging a rural borough of rivers and rock with the city of a thousand minarets.

When Deputy Consul General Heba Zaki took the Rockefeller podium, a gravity settled over the pews.

“This exhibition is important to my country and to me on a personal level,” Zaki said. “I think that there is no other time in history that we need to build bridges more than now.”

Unlike past Rockefeller exhibitions, The Bridge is not an overblown circus of ornate tapestries. This exhibition, on view until May 19, has been refined by the artists’ lived experience and thousands of years of interreligious conflict. It’s the passing mile-marker of a long pilgrimage, tucked away in a transept.

In his closing remarks, Chandler quoted the late conductor-composer Leonard Bernstein:

“The point is, art never stopped a war. That was never its function. Art cannot change events, but it can change people. It can affect people so that they are changed. Then they act in a way that may if fact change the course of events—the way they behave, the way they think.”