Acceptance rates plummet; endowments swell. America’s most prestigious private schools are locked in an endowment-fueled arms race, vying for superstar professors, talented students, and new buildings plastered with benefactors’ names. Consequently, administrators, students, and legislators are weighing in on where these funds should go. These questions have inevitably materialized on our own campus with the recent Student Government (SG) election. Even if endowment-related issues such as divesting from companies that do work with the Israeli Defense Forces or financially supporting cash-strapped Chicago State University (CSU) fall beyond SG’s influence, the ethics—and limitations—of endowments are surely on students’ minds.

While UChicago’s current endowment—currently valued above $7.55 billion—is significantly smaller than other peer institutions’ portfolios, such as Harvard’s whopping $37.6 billion portfolio, UChicago’s increasing returns on investment have allowed it to expand on its ambitious projects. The sleek, elegant Campus North façade towers over 55th Street, embodying the University’s construction initiative. Other efforts, also made possible by a growing endowment, allow for expansion beyond buildings: take, for example, the No Barriers initiative announced in 2014, which was launched with the intent of improving the University’s socioeconomic diversity.

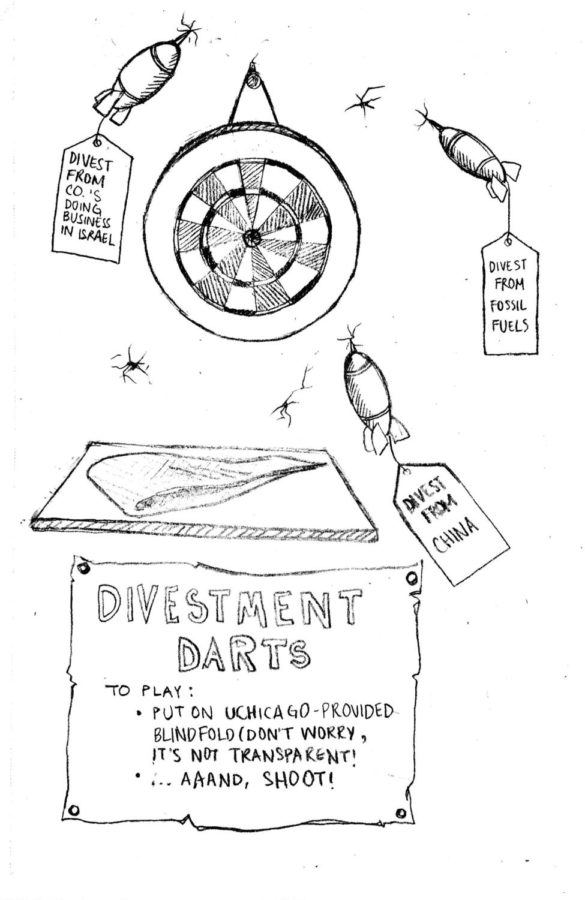

As the endowment grows alongside the campus, UChicago has also accrued sizeable debt in vying with the Ivies for prestige, as Bloomberg News reported in 2014. Although these efforts have improved student life and academics, some of the investments in UChicago’s portfolio have sparked debate on campus. Student activists have called for the University to divest from a wide range of sources: fossil fuel companies for their role in perpetuating climate change; China, for its organ-harvesting; and, perhaps most controversially, companies listed by the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement for their cited complicity in human rights violations. The latter movement’s fervent (and often tasteless) politicization of an incredibly nuanced geopolitical conflict certainly does not represent the entire student body. But the intensity of the debate, beside the usually contentious Israeli-Palestinian discourse, points to a continued lack of transparency in the University’s investment portfolio.

In 2007, the University, under President Zimmer’s leadership, declined to divest from Sudan despite the atrocities of the Darfur conflict. In defending the Board of Trustees’ decision, President Zimmer cited the 1967 Kalven Report, which promotes the University’s dedication to free inquiry over political influence. The Kalven Report has been continuously referenced as a deterrent for other divestment resolutions and proposals.

As the University continues to focus its resources on its academic arms race with other elite private institutions, the United Progress slate’s now-rescinded call to support the embattled CSU through endowment funds, while noble, was completely divorced from the reality of endowments. This lack of knowledge might stem from the mystery surrounding the endowment. This lack of transparency means we have no idea how many blood diamonds (figurative, literal, or imaginary) are in the University’s portfolio. While the administration continues to prioritize its ambitious plan to dethrone its academic rivals, it could definitely find inspiration in Stanford’s student-driven decision to divest from coal.

These contentious suggestions from the SG election—divesting from countries linked to human rights abuses and investing in salvaging the underfunded CSU—are practically misguided considering SG’s scope and knowledge but do point to a legitimate campus problem. The University and its handling of the sizable endowment lacks transparency and thus accountability. Whereas the administration defends its international interests in the name of free speech, there is something unsettling about investing in countries where free speech does not exist, among other human rights and environmental violations. More transparency is essential: if the student body is informed, we can avoid the more annoying and infeasible calls for divestment. Due to the nature of endowments, the University might not be able to release all information about its investments—but some transparency will at least help us know what we can ask for.

Felipe Bomeny is a first-year in the College.

Editor’s note: This article originally referred to “divestment from Israeli companies,” which does not accurately reflect the divestment resolution’s intent to target multi-national companies that are not Israeli, but which do business with the Israeli Defense Forces.