Superdelegates and brokered conventions have both come under fire during the current presidential campaign. Before Trump all but secured the Republican nomination, his supporters fretted over a brokered convention, arguing it would be undemocratic if it nominated anyone besides Trump. If Trump has a plurality of the Republican vote, the argument goes, how could the party justly deny him the nomination?

On the Democrats’ side, superdelegates remain the target of attack from the Sanders camp. They face withering scorn for allegedly rigging the voting process by underrepresenting support for Sanders. Although there’s certainly no love lost between Trump and Sanders supporters, the two groups have revealed a shared concern for the voting process: both groups posit that checks against the will of the people, whether in the form of superdelegates or brokered conventions, improperly diminish the democratic aspect of our political process.

Both sides assume that the majority opinion ought to be upheld—whether or not it’s actually right. They also assume that if brokered conventions and superdelegates were eliminated, our electoral process would be representative of the will of the people.

Part of their argument is correct. The majority opinion is inviolable—to a certain extent. But there are two serious problems with opposing the use of brokered conventions and superdelegates: first, our form of government isn’t intended to be a pure, unconstrained democracy, and second, even without the use of brokered conventions, our electoral process wouldn’t be representative of the will of the people anyway.

We aren’t living in a pure democracy, nor are we supposed to be. When we question the validity of checks on the democratic process, like brokered conventions or superdelegates, because they reduce our political system to something less than entirely democratic, we implicitly assert that pure democracy is the ideal. And if pure democracy is indeed the ideal, then it follows that our democracy should be entrusted entirely to the will of the people. And such an assertion is nonsense.

In our constitutional democracy (emphasis on “constitutional”), the majority cannot do whatever it wants. This should make sense; the majority has a long history of making terrible mistakes. If you seriously believe that large groups of people, by virtue of being numerous, don’t run the risk of formulating awful and illegal policy decisions, then you might expect a considerably less spotty record. Our government is built on the acknowledgement that the will of the people can be, and often is, horribly wrong. This is something we seem to know when we talk about policies we dislike; it’s something we very conveniently forget when the candidates and policies in question are ones we support (in which case, any attempt to stop the majority is unquestionably despotic).

The Constitution itself acknowledges the potential for disaster, so far as majority rule is concerned. What else do we imagine the Bill of Rights exists for? How about the 13th, 14th, 15th, and 19th Amendments? We all know that the president can veto legislation produced by the democratically elected Congress. The Supreme Court is vested with the power to override both the democratically elected executive and legislative branches. Evidently, what the majority says doesn’t always go. It isn’t supposed to!

The structure of our government was articulated with the understanding that a democratically elected government can do outrageous and illegal things, and that, where necessary, checks should be put in place to balance the process. It shouldn’t be surprising that our nomination processes reflect this spirit; just as the will of the people has failed to uniformly produce appropriate legislation, the will of the people has also failed to reliably produce qualified and electable candidates. The Democratic Party introduced superdelegates to prevent embarrassing losses, following the McGovern campaign’s disastrous loss in 1972 (he won only 17 electoral votes) and Carter’s equally disastrous reelection effort in 1980 (he won 49 electoral votes, a historical low for an incumbent).

Superdelegates are supposed to offset the effect of voters flocking to grassroots candidates who perform poorly in general elections. To be fair, the measures instituted to make the voting process less erratic—including superdelegates and brokered conventions—are undemocratic. But they are certainly not un-American.

Beyond the fact that the power of the majority is supposed to be constrained, there’s another, more significant problem with our voting process. It isn’t really representative. When we claim that brokered conventions and superdelegates thwart the will of the people, what we ought to say is that they thwart the will of the people who actually voted, or, to get even more convoluted, that they thwart the will of the voting population as represented by pledged delegates. And those two groups—the voting population and their representatives—are not at all equivalent.

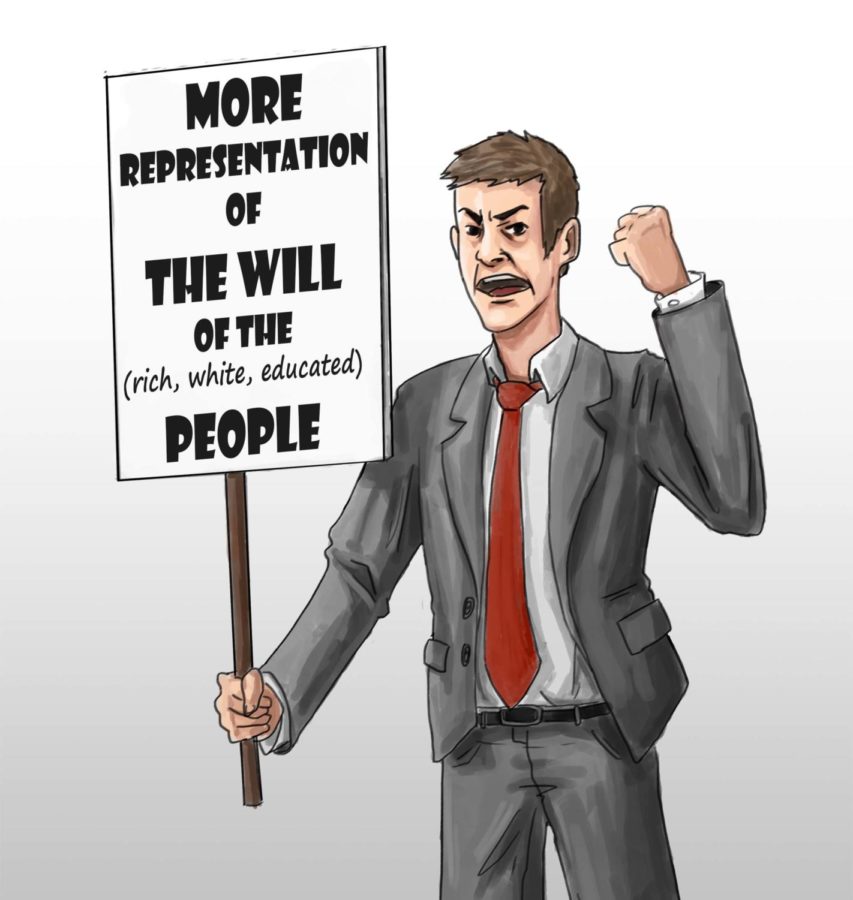

A Pew study from 2015 puts average U.S. voter turnout (as a percentage of the eligible population) at a lackluster 53.6 percent. Voters, as it turns out, are not representative of the general population; minorities are less likely to vote than whites. The Census Bureau pegs turnout for eligible voters with an “advanced degree” at 62 percent, which is far higher than the 33.9 percent of high school graduates. Those in the highest reported income bracket had a turnout of 56.6 percent, compared to 24.5 percent in the lowest income bracket.

The people voting are not representative of the general population at all, but issues with the voting process aren’t confined to turnout alone. On the Democrats’ side, low turnout combined with the realities of pledged delegate distribution has made the delegate count even less representative. According to an analysis from FiveThirtyEight, not only does Clinton lead Sanders in terms of popular votes, but Sanders’ pledged delegate support is inflated. Sanders’ delegate count draws heavily from caucus states with low voter turnout. As a result, Sanders’ support among pledged delegates was actually overrepresented as of early April—Sanders had 46 percent of pledged delegates but 42 percent of raw votes. It’s unfair to cast the blame on superdelegates for making the nomination process inequitable; in reality, pledged delegates are themselves unrepresentative, and not in the direction that you might think.

Evidently, the voting population is only part of the eligible population. It’s richer, more educated, and whiter than the general population. And, when this demographic goes to vote, the results are distributed so bizarrely that candidate support no longer reflects raw votes. All of this raises the question: how can we confuse a skewed representation of the will of American voters with the will of the American people, when the two are clearly not interchangeable?

Checks on the will of the people, including brokered conventions and superdelegates, should be appealing for fairly intuitive reasons. Governance by majority rule may be the best form of government, but it isn’t always a safe one. This holds true in the electoral process just as much as it holds true in the legislative and executive processes. What should be genuinely disturbing is not the fact that both the Republican and Democratic parties reserve the right to nominate an establishment candidate over a more popular insurgent—we should be far more alarmed by the fact that the Americans who will ultimately vote for these candidates make up only a small part of the population, and an unrepresentative part at that.

Natalie Denby is a first-year in the College majoring in public policy.