What makes somebody’s voice valuable depends on whom you ask. In the world of social justice and identity politics, the voices that are allowed to speak without question are the voices of the people who have been most oppressed. Those who have enjoyed the benefits of privilege are politely (in most cases) asked to be a listener, and perhaps even asked to remain completely out of a discussion. This mentality, while perhaps important for dialogues within these oppressed and marginalized groups, presupposes that it is the advantaged individual who should remain quiet because it is they who are somehow to blame for the wrongs the advantaged group has done. To put it simply: it is specific white men who are often blamed for the oppression of minority and marginalized groups. However, the real issue is that the privilege associated with being a white male comes with presuppositions about what it means to be white. The concept of whiteness itself is to blame for the inequalities seen in society, not specific white individuals. Despite these obvious reasons for wanting to exclude the advantaged group from a discussion about their privilege and its impact on others, it remains important to include them in the conversation.

There are emotions and sentiments that are common to all people. While I may have a limited understanding of what it means to be black or a woman, I do know what it feels like to be excluded or mistreated. It is on these common grounds that a full emotional and practical alliance can be formed. These alliances must be brought about carefully—a member of the advantaged group should always to be careful to respect the experiences of the members of marginalized groups. It will, of course, remain important to keep the oppressed history a part of the conversation. However, these discussions about history should be used as a jumping off point for further conversations that don’t necessarily focus on the oppression. By allowing the oppressed and marginalized groups to share their experiences openly, a better level of empathy can be reached. By relating the emotions that come along with systematic oppression to transhistorical human emotions like suffering and sadness, the oppressed group and the oppressive group may be able to come to a healthier relationship or a place of peace.

More practically, it is my personal belief that we should strive to live in a post-identity defined society. What I mean by this is that people will no longer have a need to feel the weight of the historic oppression or privilege of their race, gender, sexual identity, or any other arbitrary characteristic. These characteristics are only important because they are in opposition to those in the privileged group—they act as signals of deviation from a falsely accepted societal norm. But these characteristics are in no way telling about the true character of a person. Instead, they minimize the true character of people. By conforming to these categories, even by proudly reclaiming them, people ascribe to themselves and others different values based on things which have no real bearing on people’s abilities or personalities. By allowing for the dissolution of these categories through cooperative learning and sharing of emotional similarities, a post-identity based politics society can be achieved while still allowing minority groups to enjoy shared emotional experiences and a sense of history.

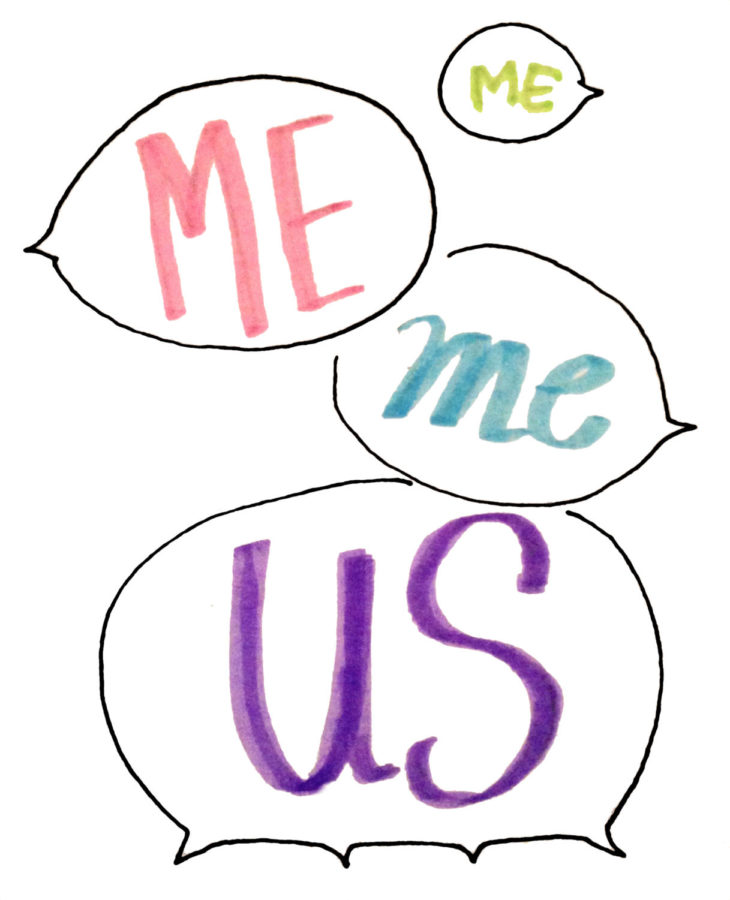

The only way to achieve this is to allow for a totally open discourse, in which every group is included. People must be completely aware of their privilege, but all parties must feel as though their voices matter and can be heard. Without this kind of open dialogue, a post-identity society cannot be achieved. Though it will remain important to keep marginalized groups as a priority voice in all of these discussions, in order to elucidate the issues that remain, the conversation must also shift to have a more equal distribution of voices before it can be finished. So long as people are in constant conversation, there can be no doubt that we can as a society move past the unpleasant aspects of identity politics.

Andrew Nicotra Reilly is a second-year in the College majoring in economics and political science.