Polling for elections centers on predicting how different groups will vote. Questions of which candidate will get the “black vote” or the “women vote” are touted as important questions for understanding who will be the next president. But this election, perhaps more than any other, has shown that these types of baseline biographical details do not go far enough to explain the way people will vote come November. The two remaining candidates represent two fundamentally different views of America’s past as well as America’s future. Trump’s optimal America is one of the past, an America with less diversity and more isolationism. Clinton’s perspective, while not necessarily outwardly progressive, posits an optimal America in which there is social progress and the acceptance of globalization. Her appeal to voters is not intrinsically linked to her own identity. She does not strive to only gain the acceptance of people who are like her in every way. Trump, however, uses his own personal identity in an unprecedented way—as a basis for his political support.

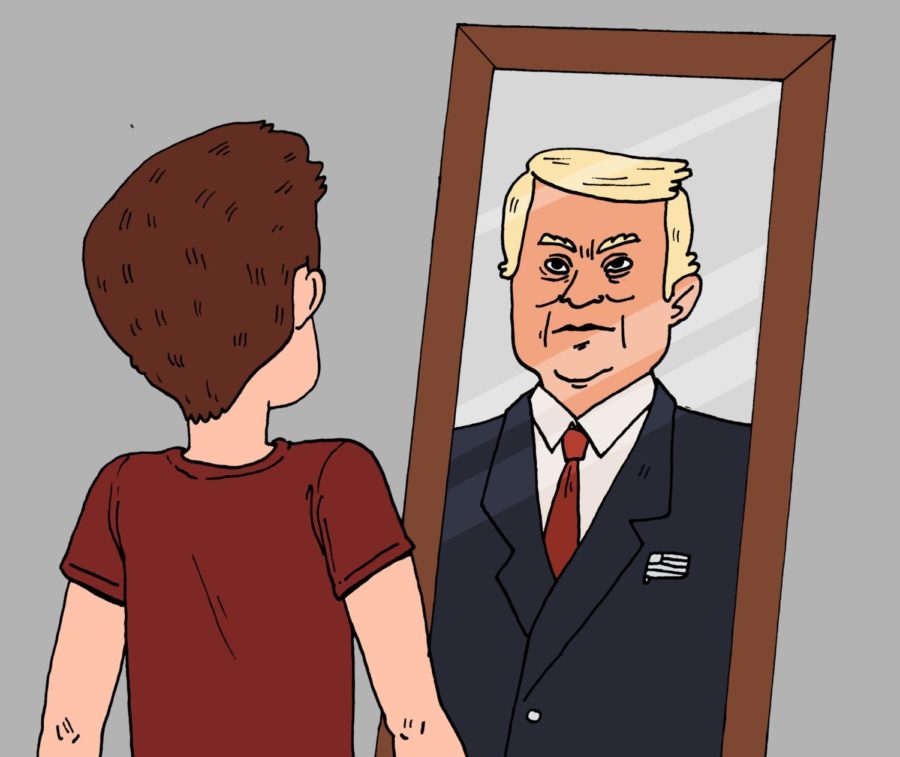

There exists a Donald J. Trump experience of America. Trump’s most significant policy concerns are business and trade generally, but his campaign is most noted for its exceptionalist rhetoric, most famously his assertion that America is no longer great. In order to “Make America Great Again,” Trump envisions a society in which immigrants are not allowed into the country so that “real Americans” face less competition in the job market. Globalist policies, embraced by establishment Republicans and Democrats alike, present a challenge, since they allegedly take jobs and money away from hardworking Americans. But who are these “Americans” in Trump’s mind? These are people, predominately white men, who feel left out of an increasingly diverse America. As such, he appeals to a demographic of people who believe that America is at its best when those in control are people like Trump.

The cult Trump has created around his candidacy is so unyielding that his supporters are willing to forgive him for any vulgar, offensive, or untrue statements he makes. A frequent rebuttal from his supporters is that Trump merely says what everybody is thinking but is too afraid to vocalize in an increasingly politically correct society. The identity of a Trump voter is thus intrinsically intertwined with the identity of Donald Trump himself. They connect with him because he is able to tap into their identity. The fear he peddles, the anger he articulates, and the success he brags about are all things his voters see within themselves or admire.

Trump appeals to people’s feelings, not their political orientations. He is a candidate of emotion and prejudice, and like the casinos he is famous for, he gives people a twisted sense of opportunity. But also like his casinos, the majority of Trump supporters will inevitably lose out. His candidacy, despite its guise of altering the status quo, is primarily built around the preservation of a predominantly white, patriarchal society. Trump supporters want people like Trump to remain the winners. For example, much of his campaign has focused around anti-immigration measures, specifically targeting Mexicans and Muslims. He has posited these two groups as holding values antithetical to American ones, thus undermining American domestic security. Ultimately he is playing into his voters’ fear that their power in society would be compromised if they were to accept different types of people. That’s why the sheer impossibility of his policy ideas, like banning Muslims or building a wall funded by the Mexican government, hardly alienate his core supporters. His voters are driven by emotion, not a reasoned consideration of what his policies would actually entail. His policy recommendations sound more like something a relative would yell in a heated Thanksgiving political argument than a coherent argument from a serious presidential nominee. But this is exactly the appeal of Donald Trump—he is a familiar face with familiar speech, and he consequently personifies the ideas, identities, and prejudices of many Americans.

This is why we cannot dismiss Trump as ridiculous. While he is certainly not offering rational solutions to America’s problems, he sheds light on the ways in which many Americans think. He is the crazy uncle at the Thanksgiving table. Many men in America share his view of women. Many people share his view of immigrants. Whether or not Trump actually believes what he himself says is unimportant, because he still represents what many Americans perceive the ideal America to be. It is only by understanding Donald Trump as the man and the identity that he has cultivated that we can begin to try and unravel the types of hatred and bigotry he represents.

Andrew Nicotra Reilly is a third-year in the College majoring in economics and political science.