“What is the role of the black artist? What duty do we have to the black collective?” Michelle M. Wright turned a question often posed to her to the audience and her fellow panel members. The panel, “Art and Life,” was hosted by the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) on Saturday, October 1, following a wrap-up of an extensive exposition on notable African-American artist Kerry James Marshall.

Wright, a professor of African American Studies and Comparative Literary Studies at Northwestern University, was flanked by longtime staff writer and chief theater critic for The New Yorker, Hilton Als, and a UChicago professor of cinema and media studies, Jacqueline Stewart.

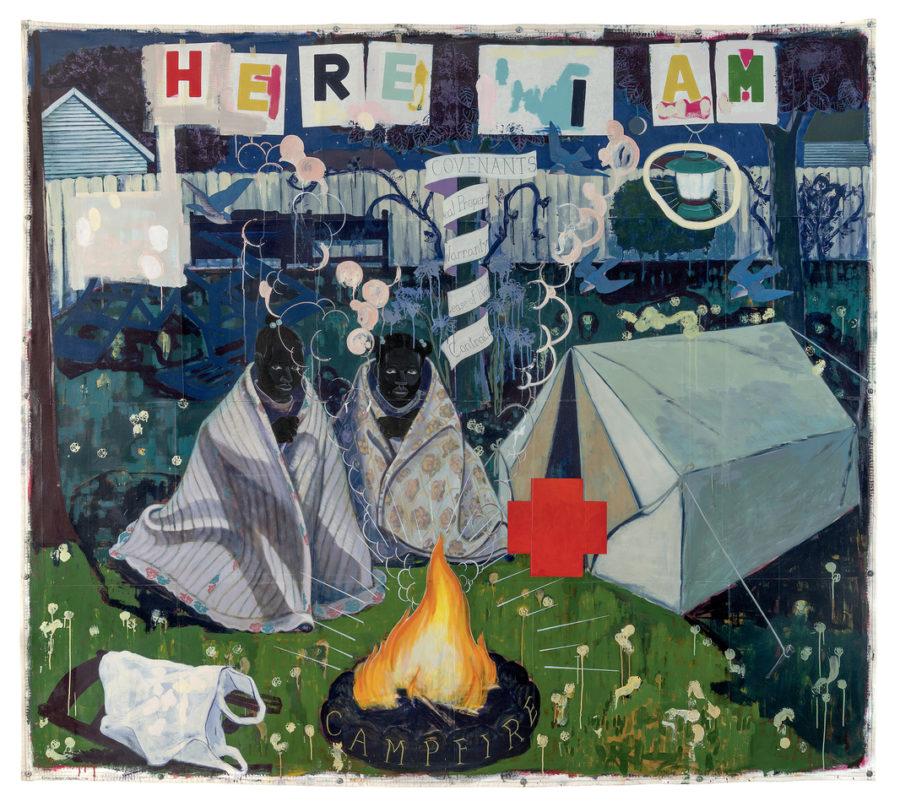

The talk focused on the intersection of art and race, using Marshall’s works as a primary example. But before the role of black artists could be explored, a more fundamental question had to be faced. How did they define “blackness”?

The panelists lingered on the many inherent paradoxes of the question. Wright complicated the prevailing definition of American blackness as “Middle Passage blackness” in reference to the slave trade of the 17th and 18th centuries. While the narrative of an identity based on common suffering and injustice created by racists carries moral and political weight, it also reduces blackness to a mere object of history instead of an agent—black art is nothing more than a reaction to white art.

Art can be a productive medium for such discussions because of the complementary work of both content and form. “We’re always talking about the ways in which blackness is diverse, to demonstrate we’re not a monolith. [Marshall] creates a visual monolith and in doing so…forces us to think about what we mean when calling ourselves black, when we call a subject black,” Stewart noted. It is through such aesthetic questions that the political and social questions can emerge.

The cultural significance of Beyoncé is such that no discussion on race and art in 2016 can be complete without including Lemonade in the analysis. Here once again the panelists felt conflicted. Beyoncé’s use of black female directors, including Octavia Butler, and her homage to independent filmmaker Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust was appreciated. Yet disappointment remained that the album missed a chance to make a bigger point, merely giving a superficial nod to its source material. What could have been a powerful statement on the state and impact of race in our pop culture was instead a move to help her husband’s business and her own brand.

“Why is it that black American culture has never put itself forward as a currency, as having value? Does it mean that we are so debased that we don’t believe in it ourselves or is it because of the power structure?” Als wondered, a theme Stewart picked up on later in reference to art. “Black audiences will value a black artist once the white world values them. [Only then will] the people who need to be showing up from the beginning begin to show up,” she said.

Als’s discussion presented equal parts humorous zingers, thoughtful ruminations—stories of his childhood and his work at The New Yorker.

In response to a comment on how blacks can express humanity in moments of crisis, Als commented, “maybe sleep with more white people,” which elicited a round of laughter from the audience, which spanned the spectrum of age and race from young black art students to a pair of elderly white women.

The Q&A at the end of panel wrapped with Als reflecting on the need for more from the black community: more art, more support for one another, and a greater sense of self-worth. And as a rebuttal to the almost attractive prospect of nihilistic black pessimism, Als offered the audience advice that his mother always taught him:

“If you have the skills and the means, why wouldn’t you be out there in the world trying to make a difference, no matter how painful it is?”