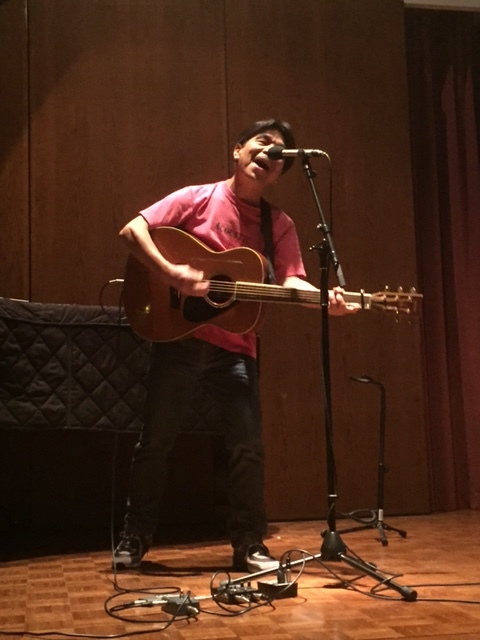

“It was the sea once/ It was the sky once—once upon a time,” Ryo Kagawa sang, his voice and guitar resonating through Fulton Recital Hall last Saturday night. “It’s you sometimes, and it’s me sometimes—nowadays.”

Presenting a set list that combined songs from his early career with selections from more recent recordings, Kagawa’s gracious and joyous performance, sponsored by the Center for East Asian Studies, marked his first live appearance in North America over the span of his 46-year career.

Kagawa first rose to prominence as a folk singer in his native Japan in the folk scene centered on Osaka and Kyoto during the late 1960s.

“There was a Tokyo folk scene, and there was a Western Japan [scene],” explained Scott Aalgaard, a doctoral candidate in the Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. “The Tokyo folk scene was very much, sort of a college folk—kids on campuses getting around in circles with acoustic guitars, doing covers of Joan Baez, Bob Dylan. But the Western Japan folk scene, in Osaka and Kyoto, was very different from that. It was a folk scene very much based on trying to express sentiments of their own…. And that’s the side that Kagawa is coming out of.”

This era in Japan was marked by social upheaval as renewals of the military alliance with the United States forged after World War II spurred protests throughout the country. The American military presence recalled still-raw memories of the war and occupation.

Several songs from Kagawa’s performance emphasized his connection to this era of Japanese history. In “Let Us Go to War,” Kagawa sang a biting condemnation of the jingoism that led Japan into World War II. After finishing the song, without pause, Kagawa lunged into “Lesson One,” perhaps his most known composition: “We have but one life; we live but once/ So don’t go and toss your life away/ It’s so easy…To falter in your stride/ When they tell you that/ ‘It’s for the sake of the nation.’”

To some Japanese, says Aalgaard, these songs are not merely nostalgic snapshots of an earlier time of blind nationalism. Rather, they retain their message and relevance in a Japan still grappling with the legacy of the American military presence. Some have accused the works of cultivating nationalist sentiment for re-fortifying Japan’s military, and attempting to rewrite certain elements of Japanese history (with Shinzo Abe at the helm of such remarks).

However, not all of Kagawa’s performance dealt with the heavy baggage of historical reckoning. In “Beale Street,” for example, Kagawa wistfully recalled the month he spent in Memphis in 1976 while recording his album Southbound Highway. Nonetheless, the songs that comprise Kagawa’s latest record, The Future, are by his own admission inseparable from another tragedy, the 2011 earthquake, tsunami, and resulting nuclear disaster that rocked Japan. Musicians, says Aalgaard, were devastated by the disaster.

“[In] the musical community in Japan, there was a really common sentiment among a lot of people….‘What the hell am I doing playing music at a time like this?’” Aalgaard said. Despite this initial reaction, Kagawa was able to discover new musical inspiration while travelling through the unbroken darkness of an area destroyed by the tsunami.

“His musical commentary and critique always seem to be about moving forward,” Aalgaard continued. Indeed, Kagawa’s ability to harness the lessons and trials of history as he gazes into the future is perhaps his greatest triumph. The continued relevance and import of his music reminds us of how easily, as he sings, “Days long forgotten are resurrected.”